Summary

William Floyd of Long Island attended the First and Second Continental Congresses. The British confiscated his farm for seven years after Floyd voted for independence.

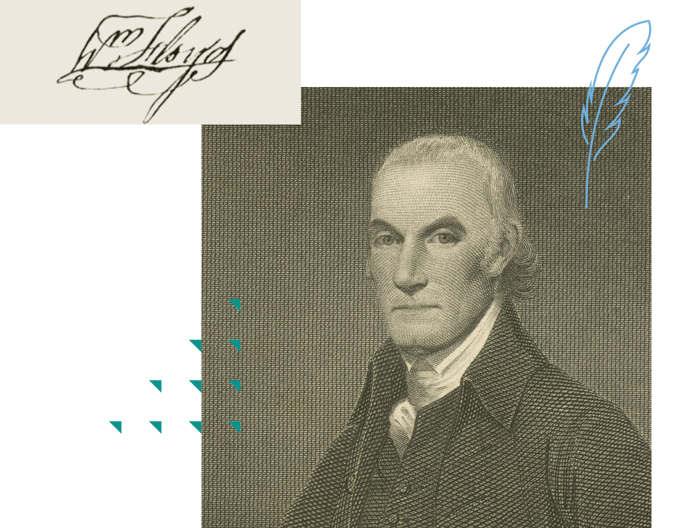

William Floyd | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:08

Biography

William Floyd was born in Brookhaven, Long Island into a farming family with Welsh and English roots. He was 21 when his father died, leaving his son the family farm. Although William appeared to have no serious education, he proved an excellent farmer and accounts manager. He produced grains and vegetables, and the farm was well stocked with cattle and fruit trees. His land fronted on the Atlantic Ocean, which gave him ready access to fish, oysters and other seafoods and allowed him to ship what he produced directly from his own dock.

The prosperity of his farm provided Floyd with an entry into local politics. He served three elected terms as a trustee of Brookhaven and was an officer in the local militia. His politics were influenced by his Connecticut friends and relatives and, by 1774, he appears to have been firmly convinced that Britain’s policies posed a threat to the liberties of its colonists. He was elected to serve in both the First and Second Continental Congress and though he rarely spoke during congressional debates he attended reliably. South Carolina delegate Edmund Rutledge described him as one of the “good men who never quit their chairs” to speak but could be counted on to be present to vote on all the major issues. Like his fellow New York delegates, Floyd was constrained by his state’s reluctance to instruct their delegation to vote yes on Richard Henry Lee’s resolution and on Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. As soon as they were given the necessary approval, Floyd joined his colleagues in signing the Declaration.

A few weeks after the Declaration was signed, the American army was defeated in the battle of Long Island [that is, the battle of Brooklyn] and Floyd’s house and farm were confiscated by the enemy. Floyd’s wife had time to bury the family silver before fleeing to the safety of friends in Connecticut. Her husband took a leave from Congress in October of 1776, explaining that he was “going to try to get some of my effects from the island if it is possible and shall be absent from Congress a few days.” On October 17, 1776, the Governor of Connecticut sent an armed party across the Long Island Sound to retrieve some of Floyd’s possessions. Nevertheless, his farm remained in British hands for seven years.

Floyd continued to serve in Congress until the end of 1776, and then became a member of the New York State Senate from 1777 until 1788. He took a seat in the 1st Congress under the new US constitution in 1789. He was a presidential elector for New York in 1792, voting for George Washington for a second term in office.

In 1794, William Floyd conveyed his Long Island property to his son and moved to a large tract of land in the frontier area of Oneida County, New York. Here , in the town of Westerville, he built a home that was a close copy of his confiscated estate.

Floyd ran unsuccessfully for Lt. Governor of New York in 1795 as a Democratic-Republican, losing to Federalist John Jay. As a state elector in 1800, he cast his vote for Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr and in 1804, for Jefferson and George Clinton. He died at the age of 86 on August 4, 1821, leaving behind an estate that included six slaves and two free black servants in residence.