Summary

William Blount said little during the Constitutional Congress debates in 1787 and reluctantly signed the Constitution. The Senate later expelled Blount due to a land speculation scheme.

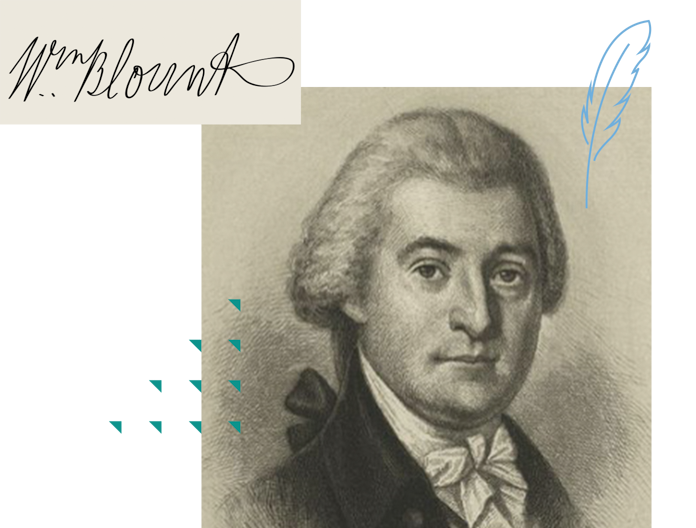

William Blount | Signer of the Constitution

2:50

Biography

William Blount was born in North Carolina in 1749, the eldest son of merchant and planter Jacob Blount and his wife Barbara Gray Blount. William was educated at home by his father and mother and became involved in his father’s mercantile and farming enterprises at an early age.

Although the Blounts had been loyal to the royal governor and to his government during the Regulator uprising, they slowly aligned themselves with the colonial resistance to British policies in the 1770s. When the revolution began, father and son both enlisted as paymasters for the North Carolina forces and thus neither saw combat. But William did help with the defense of Charleston in 1780, and his younger brother Thomas was captured during the siege. William became the official commissary to General Horatio Gates, commander of the Patriot forces in the South, but he managed to lose $300,000 intended as pay for Gates’ soldiers.

Unlike many supporters of the revolution, the Blount’s did not lose wealth; in fact, they profited from the war. Their family farms provisioned both the continental army and their state militia and thus increased their already considerable fortunes.

When William Blount returned to civilian life, he devoted himself to politics and public service—and to aggressive land speculation. As a member of the North Carolina elite, he was elected to the state’s legislature in 1781 and remained in that body for most of the decade. While in office he pressed his fellow legislators to open the lands west of the Appalachians for settlement, a move likely prompted by his interest in acquiring land there himself. Over time, he acquired millions of acres in Tennessee and in the trans-Appalachian West. Yet, by the 1790s his risky land investments would leave him in debt.

Blount served two terms in the Continental Congress before he was elected a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. He arrived late on June 20th, after debates had begun. William Pierce had an unusually favorable opinion of Blount, whose reputation in his home state was less than sterling. According to Pierce, Blount’s character was, “strongly marked for integrity and honor.” Pierce conceded however, that Blount was, “no Speaker, nor does he possess any of those talents that make Men shine; -he is plain, honest, and sincere.” Since Blount said almost nothing at all during the debates and only reluctantly signed the Constitution, Pierce’s judgment that he was no speaker might best be read ironically.

Once the Constitution was proposed to the states, Blount worked to support its ratification. He hoped to be elected to serve in the first U.S. Senate. When this did not occur, Blount moved to Tennessee and focused his energies on his land speculation ventures. He began his life there in a cabin, but by 1792 he had built a mansion in Knoxville. Blount’s success was helped by President Washington’s decision to appoint him as Governor of the Territory South of the River Ohio, a region including Tennessee. Blount was also made the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern Department. In 1796, he presided over the convention that established the state of Tennessee, and this allowed him to satisfy his thwarted wish: he was elected one of the new state’s first U.S. Senators.

Despite his political successes, Blount’s personal affairs were in crisis by the 1790s. In 1797, his land speculation took a serious toll on his finances. In that same year he devised a grandiose scheme to use elements of the British navy, frontiersman, and Native Americans, to enable Britain to annex the Spanish provinces of Louisiana and Florida. If successful, this would have opened up opportunities for new land speculation. The plan was discovered when President Adams received a copy of a letter Blount had written about it. The President handed the letter over to the Senate on July 3, 1797, and five days later the Senate voted 25-1 to expel Blount. Next the House impeached him. Blount fled to the safety of Tennessee, where he still enjoyed a loyal following. In the end, the Senate dropped any further charges, and did not vote to confirm the impeachment. Blount’s national career was over. But his career in Tennessee was not. He received a hero’s welcome on his return to Knoxville, and his allies, including Andrew Jackson, rallied around him. In 1798, he was elected to the Tennessee senate and rose to be its speaker.

In March 1800, an epidemic swept through Knoxville and several members of Blount’s family became ill. Blount too fell ill on March 11th. He died ten days later at the age of 50, ending a career as a canny politician and a reckless land speculator.