Summary

Maryland sent Thomas Stone to Philadelphia with instructions to vote against independence. But Maryland then allowed Stone to vote for it on July 2, 1776.

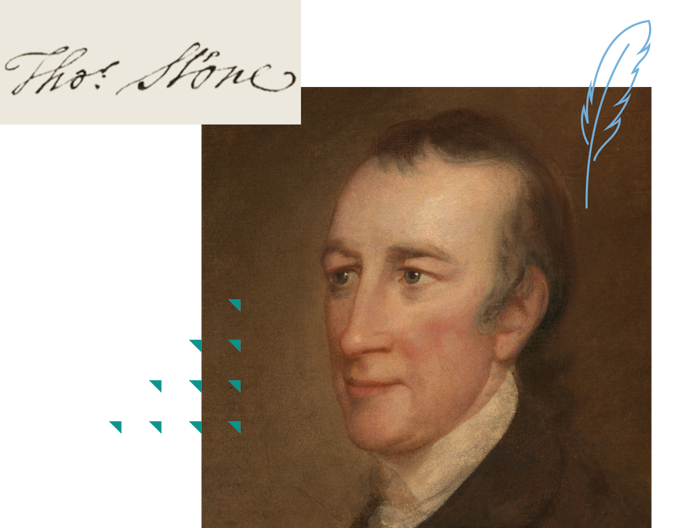

Thomas Stone | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:16

Biography

Thomas Stone, son of David and Elizabeth Jenifer Stone, was born into a distinguished Maryland family. Little is known of his early life but he attended a private school at which he studied Greek and Latin. Afterward, he studied law with Thomas Johnson in Annapolis. He was admitted to the bar at the age of 21 and began a practice in Frederick, Maryland. Here, he gained a reputation as a cautious and deliberate man, and a fine lawyer.

In 1768, 25-year old Thomas Stone married 18-year old Margaret Brown. Six years later, he entered the world of Maryland politics. By this time, the tensions between the Mother Country and the colonies had neared a breaking point, and Maryland was beginning to build connections to allies in other colonies through committees of correspondence. Stone was chosen to serve on the Charles County committee in 1773 and in 1774, he was a member of Maryland’s provisional government known as the Annapolis Convention. In 1775, soon after the battles of Lexington and Concord, the convention sent Stone to the Second Continental Congress. However, he and his fellow delegates were given strict instructions to “arrive at a happy settlement and lasting amity” with the Mother Country and they were not to vote for any proposition declaring independence.

Stone personally hoped that peace was still a possibility. Toward that end he supported a letter to the King in July 1775, assuring the monarch that the colonies were loyal and asking that their grievances be heard. The King never read this Olive Branch petition; instead he declared the colonies in rebellion.

By 1776, Stone conceded that war was likely. “You know,” he wrote to a friend in April of 1776, “my heart wishes for peace upon terms of security and justice to America. But war, anything, is preferable to a surrender of our rights.” As the debates began over independence he admitted that “The Dye is cast. The fatal Stab is given to any further Connection between this Country & Britain, except in the relation of Conqueror and vanquished, which I can’t think of without Horror & Indignation.”

A few days before the vote on Richard Henry Lee’s resolution, the Maryland government lifted its restrictions against independence. Stone, along with his fellow Maryland delegates, were free to vote yes on the resolution---and they did.

They would also sign Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence.

On July 12, Stone wrote to the Maryland Council of Safety: “May God send Victory to the Arm lifted in support of righteousness, Virtue & Freedom, and crush even to destruction the power which wantonly would trample on the rights of mankind.”

Stone remained in the Congress, serving on the committee to draft the Articles of Confederation. But, he left when his wife, who had joined him in Philadelphia, suffered a bad reaction to her inoculation for smallpox. He returned to Maryland where he accepted an appointment to the Maryland Senate.

In the 1780s, Margaret’s condition worsened and she was bedridden for many of the last years of her life. To care for her, Thomas gave up public life entirely. He gave up the practice of law as well. By 1787, her condition was critical. Writing to a friend, Stone explained that “The illness of a wife I esteem most dearly preys most severely on my Spirits, she is I think God something better this afternoon and this Intermission of her Disorder affords me time to write to you. The Doctor thinks she is in a fair way of being well in a few days. I wish I thought so….” Sadly, the doctor was wrong. Margaret died that June at the age of 36, leaving Thomas grief-stricken. In the autumn of that year, Stone’s doctors recommended that he take a sea voyage to ease the pain of his loss. He traveled to Alexandria, planning to sail from there for England. But on October 5, just four months after Margaret’s death, Thomas died. Friends believed he had died of a broken heart.

A fellow member of the Maryland Senate wrote of Thomas Stone: “he appeared to be naturally of an irritable temper, still he was mild and courteous in his general deportment, fond of society and conversation, and universally a favorite from his great good humor and intelligence…”