Summary

Thomas Jefferson was one of the youngest delegates to the Second Continental Congress, where we wrote the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson later served as vice president and president of the United States.

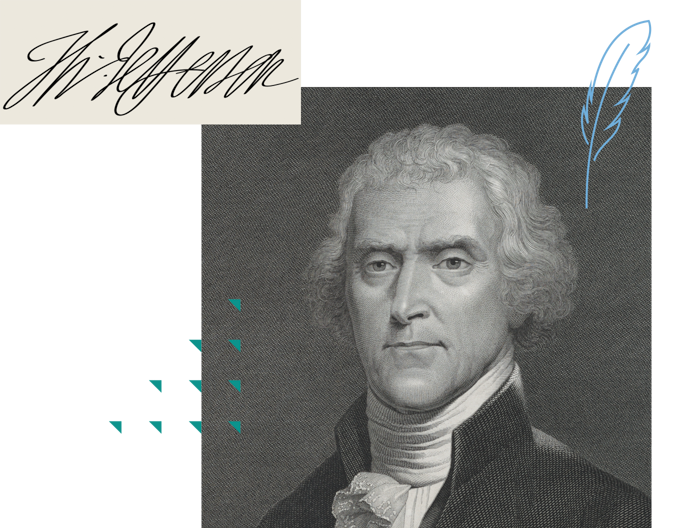

Thomas Jefferson | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

6:17

Biography

Thomas Jefferson was born at the family’s Shadwell Plantation, the third of ten children in this elite family. His father, Peter Jefferson, died in 1757 and fourteen-year-old Thomas was put under the guardianship of John Harvie Sr, who would watch over the 5,000 acres the boy had inherited. Jefferson would gain legal authority over this land when he turned 21. Thomas was well educated, studying mathematics, ancient languages, metaphysics and philosophy in locally- run schools. At 18 he entered the College of William & Mary, where he studied mathematics, metaphysics, and philosophy. At college he was introduced to the theories of John Locke, Isaac Newton, and Francis Bacon. After college he went on to read law with the distinguished attorney George Wythe. He was admitted to the bar in 1767 and, although he himself owned many slaves, he took at least seven cases of enslaved people seeking their freedom.

By 1769 he had entered the colonial government as a member of the House of Burgesses. Much of the following few years was spent constructing his own estate, Monticello, where he held many hundreds of enslaved persons over the course of his lifetime. On January 1, 1772, he married his third cousin, Martha Wayles Skelton, a widow of twenty-three. Together, the couple had six children. When Martha’s father died, Thomas took on his enslaved population and his many debts. Martha, who suffered from diabetes, died soon after the birth of her last child in 1782. She won from Jefferson a pledge to never marry again, and the grief-stricken Jefferson kept this pledge.

At the age of 33, Jefferson was one of the youngest delegates to the Second Continental Congress. Together with his newfound friend, John Adams, he served on a committee of five chosen to write a Declaration of Independence. Although the other members of the committee thought Adams should draft the Declaration, Adams persuaded them that Jefferson was the better choice. Although the Congress did not pass Richard Henry Lee’s resolution supporting colonial independence until July 2, 1776, Jefferson had been working on a formal public declaration since June 11. He presented it to the full Congress who edited it, removing a fourth of Jefferson’s original draft. They did not remove his powerful preamble, which spoke eloquently of individual and human rights. Its assertion that all men were created equal served as a driving force decades later for excluded groups like African Americans and women in their struggle to gain an equal political voice. On July 4, 1776, Congress ratified the Declaration, and on August 2 most of the delegates signed it, aware that they were committing treason in the process.

Jefferson was elected to the newly-created Virginia House of Delegates in September of 1776, and there he worked on the state constitution. He was disappointed that his effort to ensure religious freedom in the state did not pass.

In 1778 he accepted the task of revising the Virginia state laws. In this role, he led the state government to abolish what he called “feudal and unnatural distinctions” that favored the powerful landed gentry, including entail and primogeniture which vested a landowners eldest surviving son with all a father’s land and power.

As the war continued, Jefferson took on the duties of governor of his state. He was elected for one-year terms in 1779 and 1780. While in office, he transferred the state capital from Williamsburg to Richmond and introduced several reforms in public education and religious freedoms. But in 1781, Benedict Arnold, now an officer in the British military, led an invasion of Virginia. Jefferson narrowly escaped capture. He was accused by his political opponents of cowardice for taking flight. The General Assembly conducted an inquiry into Jefferson’s actions and although they did not find fault with his decision, he was not re-elected to the governorship.

In 1783, Jefferson reentered the national stage; he was elected as a Virginia delegate to the Confederation Congress. His central achievement was to author the Land Ordinance of 1784 by which Virginia ceded all the land it had claimed northwest of the Ohio River to the national government. Jefferson insisted that these lands become states and wrote an ordinance that banned slavery from all the nation’s territories. Congress, however, rejected this ban on slavery. Three years later the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 ensured that no part of the vast northwest territory would ever be colonized by the original 13 states.

In May of 1784, Jefferson was sent by Congress to Paris to join Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, who were negotiating treaties with Britain and several European countries. Less than a year later, he was tapped to replace Franklin as Minister to France. When a French official commented to Jefferson that he had heard this, Jefferson replied, “I succeed. No man can replace him.” For five years, Thomas Jefferson remained in Paris. During that time he fell in love with a married Englishwoman and soon afterward began a relationship with a young enslaved girl named Sally Hemings who had accompanied Jefferson’s daughter to France. She was, in fact, the half-sister of Jefferson’s wife Martha, born to an enslaved woman and Martha’s own father. While in Paris, Sally became pregnant. She won a promise from Jefferson that any children by him would be freed. The relationship continued when the two returned to Monticello in 1789.

Jefferson’s next service to his country was as Washington’s first Secretary of State. Conflict with Washington’s Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, began early in their terms and lasted until Jefferson resigned. At the heart of the conflict was Jefferson’s fierce opposition to Hamilton’s economic programs for the new country and the disagreement between the two men over whether an alliance with Britain or France best served America’s future.They also disagreed about whether the Constitution should be loosely interpreted— as Hamilton believed—or strictly interpreted ,as Jefferson insisted. Where Hamilton saw implied powers, Jefferson saw none. By 1792, Jefferson and James Madison had become the leaders of an opposition party, pitting their vision for America as Democratic-Republicans against the Federalist vision embraced by Hamilton and, to a great degree, by Washington himself.

The 1794 Jay Treaty with Britain proved the breaking point for Jefferson and his party, and in 1796, Jefferson ran for President. He lost the election to his one-time friend, John Adams, who had served as Washington’s vice president. Now, in 1796, Jefferson’s loss made him Vice President to Adams. The division between Federalists and Democratic Republicans now played out in Congress and in the local politics of every state. When the Adams administration passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, Jefferson and Madison responded with the Kentucky and Virginia Resolution that, in effect, claimed the states had the right to nullify a federal law they deemed unconstitutional. While this did not lead to violence or secession, it was a forerunner of the Civil War.

In the election of 1800, Jefferson defeated Adams. Both campaigns had engaged in what historians could rightly call lies and libel. Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr received the same number of electoral college votes, so the final decision fell to the Federalist-dominated House of Representatives. Hamilton lobbied for Jefferson, believing he was a lesser political evil than Burr. One of the most important aspects of the election of 1800 was the peaceful transfer of power from one party to another.

Jefferson abandoned the formal etiquette of his two predecessors and imposed a more casual style on the Presidency. He tried to soothe troubled political waters by saying in his inaugural address that “we are all Republicans, we are all Federalists,” but Jefferson’s victory—and Madison’s after him—spelled the end of Federalist political domination and led to the demise of the Federalist party. Jefferson dismantled as much of Hamilton’s economic program as he could, but he found he could not abolish the First Bank of the United States, a signature achievement of his political enemy Hamilton. Jefferson’s own signature achievement was the Louisiana Purchase, which added over 800,000 square miles to the US. Jefferson went ahead with this Purchase despite the fact that he had to rely on implied powers—the right to govern territory implied the right to acquire it—to justify his action.

Jefferson was elected to a second term, but his popularity declined. His effort to negotiate a neutral path between the two enemies, Britain and France, by an Embargo Act of both countries led to economic chaos in the US. In addition, Aaron Burr’s plot to create an empire in western lands forced Jefferson to arrest his former vice president. Jefferson openly tried to influence the verdict in Burr’s trial by proclaiming Burr guilty beyond question. He also refused to testify at the trial, claiming the novel argument of executive privilege. Burr was acquitted, but Jefferson appointed Burr’s co-conspirator James Wilkinson to be Governor of the Louisiana Territory.

Jefferson left national office in 1809, replaced as President by his ally James Madison, who in turn was replaced by a fellow Virginian, James Monroe. Thus created what has been called the Virginia Dynasty. Jefferson maintained contact with both of his successors. A mutual friend, Benjamin Rush, managed to smooth the way for a correspondence between the one time friends and long time political enemies, John Adams. Over 14 years, beginning in 1812, these two major figures in the birth of a new nation exchanged 158 letters discussing their political differences and the role of the American Revolution in world history. When Adams died on July 4, 1826, his last words were said to be “Thomas Jefferson survives,” but Jefferson had died a few hours before the New Englander.