Summary

Stephen Hopkins served as Rhode Island’s governor and he was the oldest member of the Continental Congress, except for his friend, Benjamin Franklin.

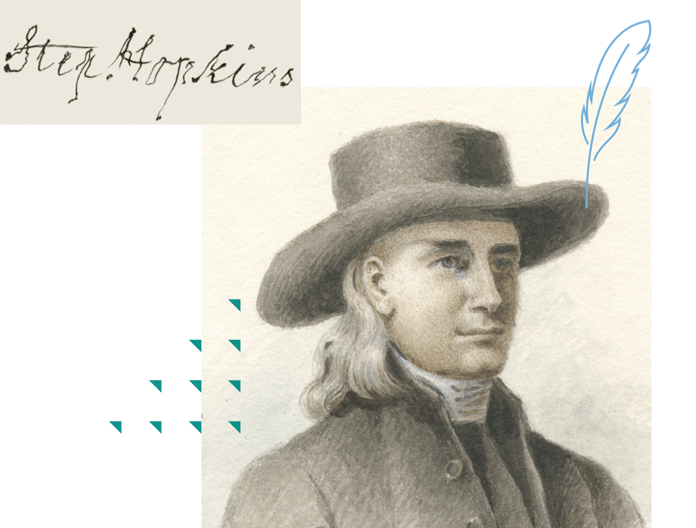

Stephen Hopkins | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:05

Biography

Hopkins was the son of William and Ruth Wilkinson Hopkins, and a descendent of one of the original settlers of Providence Plantations in Rhode Island. He was thus a member of one of Providence’s most prominent families, though not one of its wealthiest. He was also the cousin of the Revolutionary era’s most famous traitor, Benedict Arnold. Despite his notable lineage, Hopkins did not receive a formal education. His mother, grandfather and uncle gave him lessons, and he was a voracious reader, taking advantage of the many classics of English history and philosophy in his Grandfather’s small personal library. Hopkins first vocation was as a surveyor and an astronomer, but his reputation as a respected member of his community soon set him on the path to a political career. In his early twenties, the small community of Scituate selected him to moderate its town meeting. At 25, he became the town clerk and soon afterward, he rose to be president of the town council. He was chosen to represent Scituate in Rhode Island’s General Assembly from 1732 to 1741. When he was elected Speaker of this Assembly, he moved to the more settled area of Providence. Here he became a merchant who constructed, equipped and owned ships, and with four the Brown brothers [who together founded Brown University], he built an iron foundry that would later supply cannons and pig iron to the Revolutionary army.

In 1747 Stephen was appointed to the colony’s Supreme Court—although he had no law degree—and by 1755 he was the governor of Rhode Island. He had one notable political rival: Samuel Ward. The rivalry between these two men became so intense that it proved a distraction to a colony trying to cope with its tensions with the British government. The two men decided that the public good would be best served if they both pledged not to run for any office in 1768. In 1774, however, both Ward and Hopkins were chosen to represent Rhode Island in the First Continental Congress.

At 68, Hopkins was one of the oldest members of the Congress, second only to his friend Benjamin Franklin, who was born in 1706. During the Stamp Act crisis, Hopkins had penned a pamphlet entitled “The Rights of Colonies Examined” in which he attacked both the Sugar Act and the Stamp tax. He began this pamphlet with a powerful commitment to liberty, calling it “the greatest blessing that men enjoy,” and comparing it to slavery which he pronounced “the heaviest curse that human nature is capable of.” He went on to declare that “British subjects are to be governed only agreeable to laws they themselves have in some way consented.” Three years later, John Dickinson would echo these sentiments in his more widely distributed Letters from a Farmer.

By 1774, a palsy in Hopkins’s hands made any attempt at writing painful. He could, however, speak his mind in Congress. He believed that war was inevitable and gave this ultimatum to his fellow delegates: “Powder and ball will decide this question. The gun and bayonet alone will finish the contest in which we are engaged, and any of you who cannot bring your minds to this mode of adjusting the quarrel, had better retire in time”. When it came time for Hopkins to sign the Declaration of Independence, the palsy that plagued him forced him to hold his right hand with his left to steady it. “My hand trembles,” he told his fellow delegates, “but my heart does not.”

Hopkins helped to draft the Articles of Confederation, but his failing health compelled him to return to Rhode Island soon afterward. He died in July of 1785. His funeral procession was attended by judges, the President, professors and students from Rhode Island’s college, and ordinary citizens of his home state. A monument at his gravesite reads, in part, “He stood in the front rank of statesmen and patriots. Self-educated, yet among the most learned of men; His vast treasury of useful knowledge his great retentive and reflective powers, combined with his social nature, made him the most interesting of companions in private life.” The usually critical John Adams, who greatly admired Hopkins, would have agreed.