Samuel Chase signed the Declaration directly below John Hancock’s sprawling one. Chase later survived an impeachment trial as a Supreme Court justice.

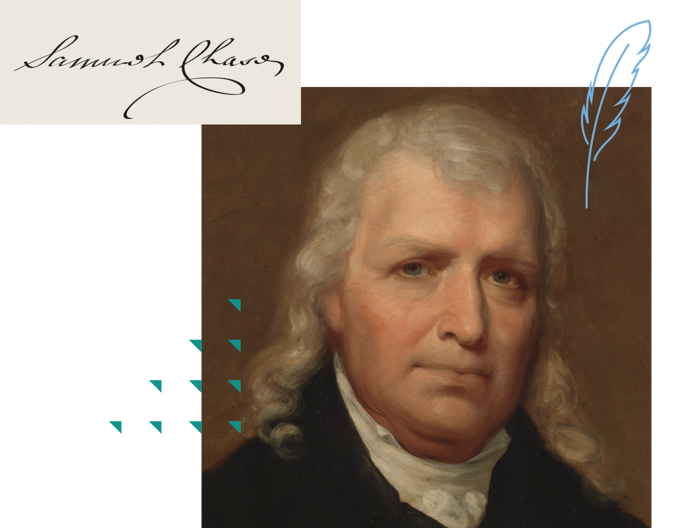

Samuel Chase | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

Samuel Chase was the only child of Reverend Thomas Chase and Matilda Walker Chase of Maryland. His mother died in childbirth, leaving Thomas alone to raise his son. Thomas was the rector of a large parish in Baltimore County. Although his stipend was barely enough to sustain him and his son, Thomas wished to be seen as the social equal of his wealthy parishioners, and he lived far beyond his means. Unfortunately, as an adult Samuel Chase would replicate his father’s desire for social recognition and the indebtedness it incurred.

Chase was educated at home, but at 18 he went to Annapolis to read law with a local attorney. Although he could not claim membership in the local elite by birth or income, he—like his father before him—was eager to be accepted socially by those who did belong. His marriage in 1762 to Ann Baldwin did not help him achieve his social goals as she was neither wealthy nor socially established. He did manage to gain admission to the prestigious Forensic Club, the local social and debating society, but was expelled in 1762 for what was only described in general terms as “extremely irregular and indecent behavior.” This would not be the last time Chase’s social climbing would lead him into trouble.

After Chase was admitted to the bar, he set up his own legal practice in Annapolis. In his early years of practice, he had to take cases that more established attorneys rejected, often working pro bono or for small fees. Yet in November of 1764, Chase decided to run for a seat in the Maryland General Assembly’s lower house. He proved a skilled campaigner, able to mobilize both the politically disaffected and his following among the middle class who depended on him for legal aid. He won the election and thus became a prominent, if divisive, figure in Annapolis politics. He remained in the General Assembly until 1784.

Chase had entered politics just as Britain began its decade-long efforts to alter the relationship between Mother Country and colonies. When Parliament passed the Stamp Act requiring, among other things, that lawyers use stamped paper for their documents, Chase refused. With his friend William Paca, he answered a call to organize a Sons of Liberty group in Annapolis, and this added to his reputation as a leading figure in Maryland politics. In 1773, he was a founding member of Maryland’s Committee of Correspondence. By 1774, when a provincial convention endorsed a boycott of British goods, Chase was solidly in opposition to continued British rule. He was elected a delegate to the First Continental Congress and quickly formed alliances with men like John Adams, who became a lifelong friend.

Debate in the Congress focused on the key question: reconciliation or independence. By 1775, Chase believed Britain had to make a choice: it “must either give up the Right of Taxation, or force obedience by the Sword.” Chase doubted Britain would give up any power. Writing to New York delegate James Duane, he said: When I reflect on the enormous Influence of the Crown, the System of Corruption introduced as the Art of Government, the Venality of the Electors (the radical Source of every other Evil), the open and repeated violations, by Parliament of the Constitution . . I have not the least Dawn of Hope in the Justice, Humanity, Wisdom or Virtue of the British Nation. I consider them as one of the most abandoned and wicked People under the Sun …Our Dependence must be on God and ourselves.”

Chase returned to the Second Continental Congress, firm in his commitment to independence. On April 28, 1776, he advised John Adams that Massachusetts should prepare for war. “Do not spend your precious Time on Debates about our Independency,” he wrote, for “In my Judgement You have no alternative between Independency and Slavery, and what American can hesitate in the Choice, but don’t harangue about it, act as if it were [independent]. Make every preparation for War, take all prudent Measures to procure Success for our Arms, and the Consequence is obvious.”

Chase was not at the Congress when the vote for independence was taken. He was in Annapolis, caring for his wife who was seriously ill. [She was dead by 1779] But on August 2, he signed the Declaration, his small signature directly below John Hancock’s sprawling one. He then returned to Annapolis, to take up his law practice and to help write the Maryland Constitution.

Chase played no role in writing the US Constitution. When he first read it, his opinion was negative. He believed the convention had exceeded its authority and that the government they proposed would “swallow up the hitherto sovereign states.” But Maryland’s political leaders thought otherwise. They were strongly Federalist and saw to it that the Maryland ratifying convention voted yes on the adoption of the Constitution. Chase’s adamant opposition to the Constitution had consequences: after 1788, Samuel Chase never held legislative office again.

Gradually, Chase’s views on the new government softened, and his Antifederalist position was forgiven by Maryland’s Governor, who appointed him Chief Judge of the General Court. In 1795, James McHenry urged President Washington to appoint Chase to the next vacancy on the Supreme Court. By January of 1796, Washington agreed. The Senate confirmed his appointment, although some Senators could not forget or forgive Chase’s original opposition to the Constitution.

When Jefferson won the presidency, he planned to transform the courts into a Republican stronghold. To hurry along the replacement of judges, he turned to impeachment rather than waiting for men to die or retire. He decided to test impeachment on Samuel Chase. All he needed was an excuse. He found it in May 1803 when Chase pressured a Baltimore Grand Jury not to defend a Maryland law granting universal male suffrage. Eight articles of impeachment were drawn up and presented to the House of Representatives, but it did not act before Congress adjourned. Chase knew his impeachment would be on the agenda when Congress reconvened in early 1804.

The trial lasted six days and Chase was acquitted. Chase remained on the court, but he appeared a defeated man. He was ill, crippled by arthritis and gout, and deeply in debt, and the disgrace of impeachment lay heavily on his spirits. By 1807 he had begun to miss sessions of the court, and in June of 1811 he died of what his doctors called the “ossification of the heart.”

In 1807 Joseph Story had described Chase as “a rough, but very sensible man . . . I suspect he is the American Thurlow— bold, impetuous, overbearing, and decisive. I am satisfied that the elements of his mind are of the very first excellence; age and infirmity have in some degree impaired them. His manners are coarse, and in appearance harsh; but in reality, he abounds with good humor. He loves to croak and grumble, and in the very same breath he amuses you extremely by his anecdotes and pleasantry.” In 1820, John Quincy Adams wrote what might be considered a eulogy for Chase in his diary: “I considered Mr. Chase as one of the men whose life, conduct, and opinions had been one of the most extensive influences upon the Constitution of this country… He was a man of ardent passions, of strong mind, of domineering temper. His life was consequently turbulent and boisterous.”