Summary

Rufus King was a leading advocate of a new frame of government at the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

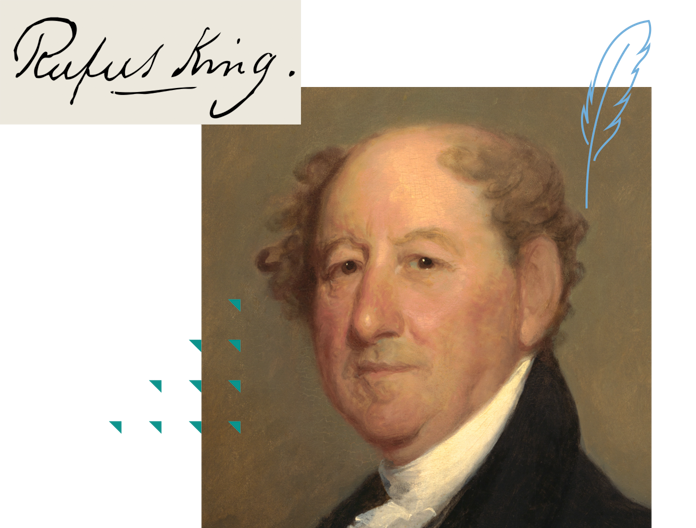

Rufus King | Signer of the Constitution

3:36

Biography

Rufus King was born in Scarborough, Massachusetts in 1755, the eldest son of a wealthy merchant and farmer, Richard King, whose success aroused the jealousy of his neighbors. Richard King would remain loyal to the King throughout the revolutionary era, and this prompted a mob to take advantage of anti-British sentiment during the Stamp Act crisis. The mob ransacked the family home and destroyed most of the furniture. This mob violence led John Adams to write to his wife that he was “engaged in a famous Cause; The Cause of [Richard] King,of Scarborough vs. a Mob.” Adams’s sympathy was profound: “The Terror, and Distress, the Distraction and Horror of this Family,” he wrote, “cannot be described by Words…It is enough to move a Statue, to melt an Heart of Stone, to read the Story…” Despite the harsh treatment of his father, Rufus King supported the movement for independence.

Rufus King graduated from Harvard College in 1777, by this time independence had been declared and war had begun. Although he had begun to read law, King interrupted his studies to volunteer for militia duty. He rose to the rank of Major and briefly served as an aide to General John Sullivan. He then returned to his study of law and was admitted to the bar in 1780. He set up a practice in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and by 1783, he had entered politics as a member of the Massachusetts assembly. Between 1784 and 1787, he was a delegate to the Confederation Congress. He was among the youngest men to serve in that body.

In 1787, King was chosen to attend the Constitutional Convention along with Elbridge Gerry, Nathanial Gorham, and Caleb Strong. At the age of 32, he was one of the youngest delegates at the convention. In his sketch of King, William Pierce sang his praises. “Mr King,” he wrote, “is a man much distinguished for his eloquence and great parliamentary talents….In his public speaking there is something peculiarly strong and rich in his expression, clear and convincing in his arguments, rapid and irresistible at times in his eloquence…” And then came Pierce’s typical “but,” for he felt obliged to note that King had a “rudeness of manner” that was unwelcome. Nevertheless, he declared King, “may with propriety be ranked among the Luminaries of the present Age.”

Although when he came to the Convention, King was skeptical that major changes to the Articles were necessary. But he soon was won over by the nationalists’ arguments and emerged as a leading advocate of a new frame of government. He served on key committees like the Committee on Postponed Matters and the Committee of Style. And like James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, William Pierce, and William Paterson, King took notes on the convention proceedings–notes valued by historians of the era. And, like 38 other delegates, he signed the Constitution.

In 1788, at the urging of his friend Alexander Hamilton, King gave up his law practice in Massachusetts and relocated to New York City. He was soon elected to the state legislature and became one of New York’s first U.S. Senators. He was an ardent Federalist and endorsed Hamilton’s financial programs and defended the controversial Jay Treaty. In 1796, he was appointed to serve as Minister to Great Britain. The appointment came as relations between the U.S. and Britain had become increasingly tense. Both France and England were violating American rights on the high seas, but the British insistence on impressing, that is seizing, sailors on American merchant marine vessels claiming they were British citizens, was seen as an especial blow to American sovereignty. King returned to the U.S. unable to produce a change in this British policy, but nevertheless having soothed the relationship amid the two nations.

Back in the U.S., King was drafted in 1804 to run on the Federalist presidential ticket with Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. They were roundly defeated by Jefferson. After this, King seemed to retire from politics. During the War of 1812 his peaceful life on his Long Island estate was interrupted again by his election to the Senate as a voice against the War. However, the British attack on Washington D.C., made him support the war. Then in 1816, the Federalists drafted King to be their presidential candidate, but he lost badly to James Monroe. For the remainder of his political life, he was consumed by a belief that the issue of slavery must be settled if the country were to survive. He called for compensated emancipation and then colonization of the free African Americans to Africa.

In 1825 with his health failing, King retired from the Senate. But, when President John Quincy Adams asked him to once again serve as Minister to Great Britain, he agreed. Soon after arriving in England, he fell ill and returned home. In 1827, at the age of 72, he died.