Summary

Robert Treat Paine hoped separation from Britain would not become necessary, but he signed the Declaration after the crown rejected a petition to avoid war.

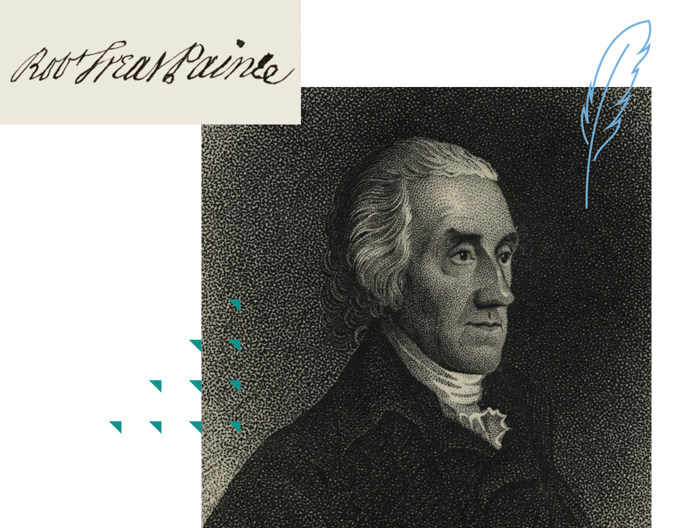

Robert Treat Paine | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:20

Biography

Robert Paine was born in Boston to Thomas Paine and Eunice Treat Paine. His father had been a pastor but had given up his clerical role to become a merchant. As the son of prosperous parents, Robert attended the noted Boston Latin School and then, like many socially privileged young men, went on to Harvard at the age of 14. He graduated in 1749, just as his father lost his fortune, and Paine taught school for a year, just as his fellow graduate John Adams did for a few years. Paine tried his hand in the mercantile world, including acting as the master of trading ships, but he was met with little success. By 1755 he was reading law with his mother’s cousin. In 1757 he was admitted to the bar. In 1761 he set up a practice in Taunton, a setting less competitive than Boston. Decades later, he would return to Boston.

Paine’s move to Taunton established him as one of the town’s leading citizens. By 1763 he was a justice of the peace. By 1768 Paine was serving as a delegate to an unauthorized assembly gathered to make public the colonists’ grievances against what they considered Britain’s growing oppression of its colonies. Paine’s reputation as a critic of the Mother Country was firmly established in 1770 when he joined the Solicitor General of the colony, Samuel Quincy, in prosecuting the British soldiers involved in what Americans called the Boston Massacre. John Adams took on their defense and, although it was Adams’s arguments that won acquittal for the soldiers, Paine’s own reputation was burnished by his role in the courtroom.

By 1773, as the tensions between Britain and the colonies neared the breaking point, Paine took his seat in the Massachusetts legislature known as the General Court. Yet he still held out the hope that separation from Britain would not become necessary. Slowly he changed his mind. By 1774 he agreed to serve in the Provincial Congress, a body created in response to royal Governor Thomas Gage’s refusal to convene the Massachusetts legislature. In effect, the Congress was a major step in seizing control of the political reins in the colony. Massachusetts then sent Paine to the Second Continental Congress, where he signed the colonial peace offering known as the Olive Branch Petition, a last-ditch effort to avoid war with the Mother Country. The petition was rejected by the Crown. Thus when the Congress voted for independence in 1776, Robert Treat Paine signed the Declaration.

On July 6, 1776, Paine wrote to his friend Joseph Palmer, arguing that Americans had much to gain and little to lose by declaring Independence. “It is,” he said, “our comfortable reflection, that if by struggling we can avoid the servile subjection which Britain demanded, we remain a free and happy people; but if, through the frowns of Providence, we sink in the struggle, we do but remain the wretched people we should have been without this declaration. Our hearts are full, our hands are full; may God, in whom we trust, support us.”

Paine chaired the Congressional Committee on Ordnance and he pressed hard for increasing the domestic manufacture of gunpowder, muskets, and artillery. In a letter to a friend, he expressed his frustration with the priorities of his fellow Americans: “I wish the Inhabitants of the United States were more intent upon providing and manufacturing the Means of defense, than making Governments with[ou]t providing for the means of their support.”

Paine returned to Massachusetts at the end of December 1776, and in 1777 he was elected Speaker of the state’s House of Representatives. In 1780 he was a member of the committee that drafted the state constitution. He became Massachusetts’ Attorney General in 1777 and held that position until 1790. During these years it was his duty to prosecute the treason trials of Shays’ Rebels. But he also prosecuted a case, Commonwealth v. Jennison, that proved pivotal in the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts. His last public service was as a justice of the State Supreme Court from 1790 to 1804.

Paine enjoyed a peaceful retirement until he died in 1814 at the age of 83. He was remembered fondly by an early female historian, Hannah Mather Crocker. “No man loved wit better than he did,” she wrote. “He often appeared lost in profound thought but could relax in a moment at the sound of a witty speach [sic].”