Summary

In 1775, Robert Morris was likely the richest man in America. He signed the Declaration and was considered the financier of the Revolution. He also attended the 1787 Constitutional Convention.

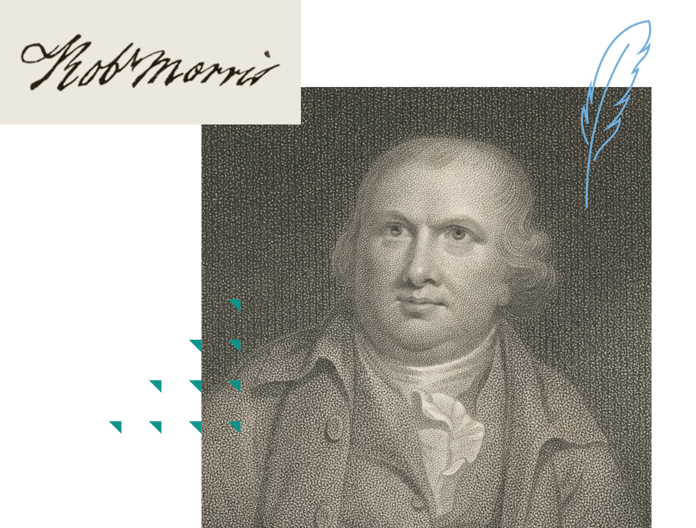

Robert Morris | Signer of the Declaration of Independence and Constitution

2:44

Biography

Robert Morris, Jr. was born in Liverpool, England. There is some suspicion that he was born out of wedlock. He was raised by his maternal grandmother until he reached the age of thirteen, when his father, who was building a fortune in the tobacco trade, brought him to Oxford, Maryland. After two years, Robert, Jr. was sent to live in Philadelphia and was apprenticed to Charles Willing’s shipping and banking firm. In 1750, his father died from an infected wound, leaving most of his large estate to his son. By 1757, Robert Morris was a full partner in the Willing firm. Among the imports by the Willing, Morris & Company in 1762 were 200 enslaved persons, sold at auction. The firm also held auctions for other importers of Africans. By 1775, Robert Morris, Jr. was likely the richest man in America.

At the age of 35, Morris married 24 year old Mary White, the daughter of a wealthy lawyer and landowner. The couple had seven children, but Morris had also fathered an illegitimate daughter half a dozen years earlier. He supported her and remained in contact with her and his younger half-brother, who Morris, Sr. had sired out of wedlock as well. This boy, Thomas, was later made a partner in Morris’s shipping firm.

Morris was not a firebrand; in fact, although he opposed British policies in the 1760s and 70s, he preferred reconciliation with the Mother Country rather than a serious break with the Crown. When he was elected to the Continental Congress, he aligned himself with its least radical faction. He did, however, agree to serve on the “Secret Committee of Trade” which supervised the procurement of arms and ammunition, a decision that later on would make him vulnerable to attacks of mismanagement from several fellow delegates.

By 1776, as efforts to draft a state constitution began, Pennsylvania’s leaders grew frustrated with Morris’s conservative stance. At the same time, Congress itself was seriously debating American independence. By July of that year, Pennsylvania’s delegation was the only delegation opposed to declaring independence. Morris refused to cast a vote for separation from Britain, but he and one fellow delegate agreed to excuse themselves so that those favoring independence could constitute a majority in the Pennsylvania delegation. With all the delegations voting in favor, Richard Henry Lee’s resolution declaring independence was passed on July 2.

Despite Morris’s obvious reluctance to support independence, Pennsylvania sent him back to Congress. In August, Robert Morris signed Jefferson’s Declaration. He explained his capitulation to Horatio Gates that October: “I am not one of those politicians that run testy when my own plans are not adopted. I think it is the duty of a good citizen to follow when he cannot lead.” He added, “I do not wish to see my countrymen die on the field of battle nor do I wish to see them live in tyranny.”

In September 1777 Morris asked for, and received, a leave of absence from Congress, but wound up spending much of his time defending himself against the attacks that he had mismanaged the procurement of arms and ammunition and committed financial improprieties on the secret committee of trade. He thus played little role in the drafting of the Articles of Confederation, but signed it when it was completed.

Morris returned to Congress in the Spring of 1778, but his mind was on his own business affairs and he took on very few assignments. Even after he left Congress permanently, he was hounded by Henry Laurens, Tom Paine, and others who again alleged he had used his position in Congress for his own financial benefit. In 1779, this cloud over his head was finally lifted when a congressional committee cleared him of all charges.

Home in Pennsylvania, Morris joined forces with James Wilson to organize a Republican Society. This political club wanted to replace the highly democratic state constitution with a more conservative one. They argued for a bicameral legislature, an executive with veto power, an independent judiciary, and a separation of powers that would appear in 1787 when the new national constitution was written. Although men like Dr. Benjamin Rush, Thomas Mifflin, and Wilson supported this goal, Morris was clearly its leading proponent. Not surprisingly, he was not reelected to Congress.

Morris was restored to popularity when, in 1780, he led a group who created a Bank of Pennsylvania to fund the purchase of supplies for the struggling army. The following year, as Congress faced a financial crisis and a mutiny by near- starving troops, he was appointed by them to be the Superintendent of Finance. His mission was to resolve the financial crisis that led to drastic shortages of military supplies for Washington’s army. Morris instituted several reforms aimed at boosting the American economy. Most bore the mark of the economic ideas of English theorist Adam Smith who urged laissez-faire policies in his 1776 book, The Wealth of Nations. Soon after accepting the committee assignment, Morris convinced Congress to establish the Bank of North America. The bank, built on the ideas of Morris and his colleague Gouverneur Morris, was a private institution governed by its investors but run under the supervision of the Superintendent of Finance. It was designed to lend money to Congress and issue bank notes. Morris believed it would help finance the war and stabilize the nation’s currency. Until the bank was operational, Superintendent Morris would purchase all the supplies for the army. He came to be considered the financier of the Revolution.

After the British surrender at Yorktown, Morris issued a “Report on Public Credit” that called for the full payment of the country’s war debt through new revenue measures. Writing to the governors of every state, he argued that it was “high time to relieve ourselves from the infamy we have already sustained.” We must, he said, “rescue and restore our national credit” by bringing in revenue through tariffs. Although all the states except Rhode Island agreed, one dissent was enough to block this proposal. When the new federal government began, its Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, issued a report on public credit that echoed Morris’s earlier proposals.

By 1784, Morris was ready to end his role in government. He resigned from Congress in November of that year. But in 1787, he was once again deeply involved in national affairs for he was chosen to serve as a delegate to the convention meeting in Philadelphia. Here his proposal that George Washington serve as chair of the convention was passed by unanimous vote. Morris said little during the debates that followed but he did sign the Constitution. After the Constitution was ratified, Pennsylvania sent Robert Morris as one of its first representatives in the U.S. Senate. Here, he pressed the government to adopt many of the same policies he had advocated as Superintendent of Finance, including a federal tariff, a national bank, a federal mint, and the funding of the national debt. All of these policies became reality.

Meanwhile, Morris began to suffer personal financial problems. Lawsuits plagued him and forced him into bankruptcy. He turned increasingly to land speculation to recoup his fortune but suffered losses, especially when war in Europe ruined the market for land. The company he ran collapsed. The Panic of 1797 left Morris selling his household furniture at public auction. All he had left in his once elegant Philadelphia home was some bedding, some clothing, a few bottles of wine, and kitchen supplies like sugar coffee and flour. Morris hoped to evade angry creditors by moving to his country estate, but his creditors caught up with him. In the end, he was arrested and imprisoned for debt from February 1798 until August 1801. His release from debtors prison came only after Congress passed the Bankruptcy Act of 1800, enacted in large part to secure his release. The man who had once owned the western half of New York State now owned little more than an old gold watch that had belonged to his father. He left the watch to his son Robert.

Robert Morris, friend of George Washington and other leaders of the new nation, died of the asthma that had often incapacitated him on May 8, 1806. John Adams described him when they both served in the Continental Congress as a man who had “a masterly understanding”, and French Minister M. De Chastellux remembered him as “a large man, very simple in his manners, his mind…subtle and acute, a zealous republican…[who] always played a distinguished part in social life and in affairs.”