Summary

Richard Stockton was one of the most eloquent attorneys in the colonies. He was the first person from New Jersey to sign the Declaration.

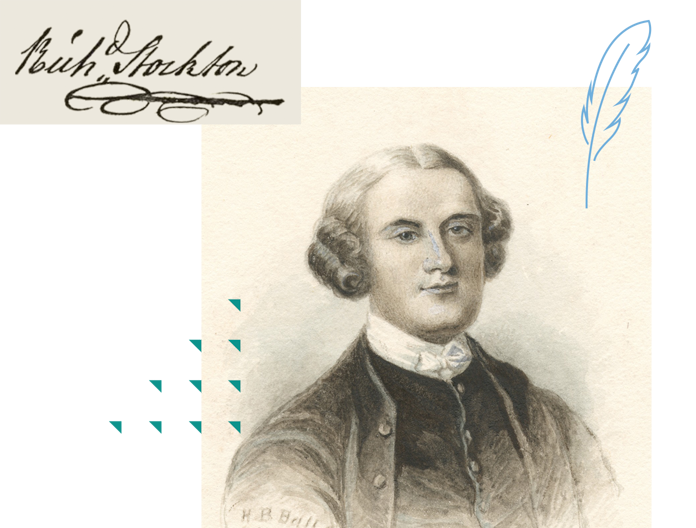

Richard Stockton | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:12

Biography

Richard Stockton was born in Princeton, New Jersey, the eldest of eight children of wealthy landowner John Stockton and his wife Hannah. As a boy he received an excellent academy education and went on to study at the College of New Jersey [now Princeton University]. He then studied law with the leading attorney in his colony and was admitted to the bar when he was 24 years old. A few years later, he married Annis Boudinot, daughter of a successful merchant and sister to Elias Boudinot, who married Stockton’s younger sister.

Stockton was acknowledged as one of the most eloquent attorneys in the colonies. Yet he gave up his legal practice in 1766 to visit England, Scotland, and Ireland. Here he was greeted warmly by British aristocrats who appreciated the tall and handsome American visitor’s polished manners. While he was in England he was presented to King George III himself. When Stockton returned to New Jersey in 1767 he came with a personal coat of arms and a motto that read “Omnia Deo Pendent”—all depends on God.

Stockton’s choice of a motto was in keeping with his longstanding aversion to entering public life. “The public,” he said, “is generally unthankful, and I never will become a Servant of it, till I am convinced that by neglecting my own affairs I am doing more acceptable service to God and Man.”

Yet after returning to America in 1767, Stockton’s attitude toward public service and political engagement grew. By 1768 he had been given a seat in New Jersey’s Provincial Council. As the tensions increased between the Mother Country and the colonies, he believed that a compromise must be reached. In 1774, he sent Lord Dartmouth a plan for self-government in America that would make the colonies independent of Parliament, but loyal to the Crown. “If something of the kind was not done,” he warned Lord Dartmouth, “the result would be an obstinate, awful, and tremendous war.”

By 1776, Stockton knew that such a war was necessary. In June, he headed to the Continental Congress. He and his fellow delegate and good friend John Witherspoon arrived in Philadelphia on July 1. They had been delayed by a violent thunderstorm and thus had missed a critical speech John Adams had given favoring independence. Richard Stockton insisted that Adams repeat what he had said. After listening to Adams’ argument for declaring the colonies free, Stockton knew that independence was imminent and that he would choose his native land over the Mother Country.

In late August, Stockton was told that he was tied for the position of Governor of New Jersey. He was not interested in serving however. He also declined to serve as Chief Justice of the state. His place, he believed, was in Congress. He was reelected to the Second Continental Congress that November and was the first person from New Jersey to sign the Declaration of Independence.

That fall he was sent by Congress to inspect the northern army and to determine what supplies it needed. He wrote to Congressman Abraham Clark that his “heart melts with compassion” for the soldiers he met for “There is not a single shoe or stocking to be had in this part of the world.” If those supplies were available, he continued, “I would ride a hundred miles through the woods, and purchase them with my own money.”

Later that same year he was captured on a trip for Congress to Fort Ticonderoga. He was dragged from his bed, put in irons, and treated as a criminal. After five weeks in prison he was released on parole, his health ruined. He returned to his home to find it plundered of its books and furniture by the British army. His horses, cattle, hogs, sheep, and grain had been taken. Stockton’s son-in-law, Benjamin Rush, believed the damage was over five thousand pounds.

Stockton resigned from Congress. When his health seemed to return, he attempted to reopen his law practice. But two years after his parole from prison he developed cancer of the lip and this soon spread to his throat. He did not survive to see victory in the war for independence. He lived in pain until he died in 1781. Stockton’s wife, the poet Annis Boudinot Stockton, survived her husband by nearly twenty years.

In his eulogy Rev. Doctor Samuel Smith, the Vice President of the College of New Jersey, described Stockton as “a man who hath been among the foremost of his country, for power, for wisdom, and for fortune.” And, the New Jersey Gazette declared that Stockton had discharged the duties of his many important offices with “ability, dignity, and integrity.”