Summary

Richard Dobbs Spaight attended every session at the Constitutional Convention. and endorsed its decision to enact a more effective government. He later died after a duel with a political opponent.

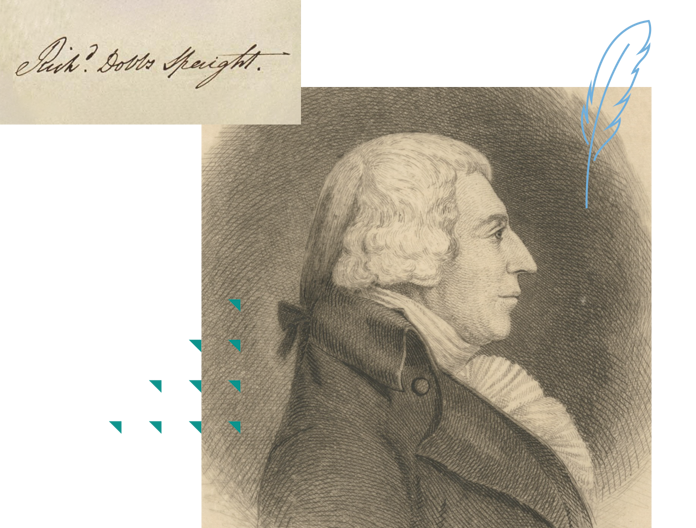

Richard Dobbs Spaight | Signer of the Constitution

2:29

Biography

Richard Dobbs Spaight, Sr. was born at New Bern, North Carolina, in 1758. He was orphaned at the age of 8, and his guardians sent him to Ireland for his education. He returned to North Carolina in 1778 when he was 20. His social status earned him a commission in the army, and he served as an aide to his state’s militia commander. While in the military Spaight was voted into the lower house of the state legislature, and by 1781 he had returned to civilian life in order to focus on his political career. Spaight served in the legislature from 1781 to 1783 and again, this time as house speaker, from 1785 to 1787. In the intervening years, he was a delegate to the Continental Congress.

Spaight was 29 when he joined the convention that was meeting in Philadelphia. He, along with fellow North Carolinian William Richardson Davie, New Jersey’s Jonathan Dayton, and Maryland’s John Francis Mercer – all in their 20s—were the youngest of the constitution’s framers. William Pierce, who drew character sketches of his fellow delegates, did not think Spaight was brilliant, but granted that he had the ability to discharge any public trust assigned to him. Spaight proved to be highly responsible, attending every session at the Convention. He spoke on several occasions and endorsed the Convention’s decision to replace the Confederation with a more effective government. Writing to James Iredell in August of 1787, he declared that “There is no man of reflection, who has maturely considered what must and will result from the weakness of our present Federal Government,” and he shared James Madison’s hope that an “energetic” new government would end the tyrannical and unjust proceedings of most of the State governments.

Spaight worked hard to ensure North Carolina’s ratification of the Constitution. Once the new government was in place, he hoped to serve in the U.S. Senate, but both his bid to be governor of his state and his candidacy for the Senate in 1789 failed. Poor health took him out of the public eye from 1789 to 1792, but on his return to politics he achieved one of his long-held goals: the governor’s seat in North Carolina. In 1798, he won election to the U.S. House of Representatives where he seemed to abandon his support for the Federalist agenda. He favored the repeal of the Alien and Sedition Acts, and, as a presidential elector, he cast his vote for Jefferson in the 1800 election. By the time he returned to state government in 1801, it was clear that Spaight had shed his earlier commitment to the Federalists and was now a Democratic Republican.

In 1802, Spaight’s shift in party loyalty became an issue in the heated contest for a seat in the state legislature between him and John Stanly. Stanly, a Federalist, insisted Spaight’s political shift was a mark of disloyalty, implying that Spaight could not be trusted. Spaight responded to the insult, accusing Stanly of “falsehoods.” Although they seemed to reach some kind of gentlemen’s agreement that allowed both to save face, Spaight upset the uneasy peace by making gratuitous comments about Stanly in the press. Stanly published his retort, accusing Spaight of false bravado and unmanly actions, loaded insults in this era. Spaight replied in print, denouncing his opponent as a liar and a man of disreputable character and immoral behavior. At this point both men agreed: the stalemate could only be resolved by a duel. It took four rounds of shots, but Stanly’s bullet at last found its mark and Spaight died the following day. He was 44 years old.