Summary

Pierce Butler was an ardent and outspoken nationalist at the Constitutional Convention. and he introduced the Fugitive Slave Clause to protect slavery.

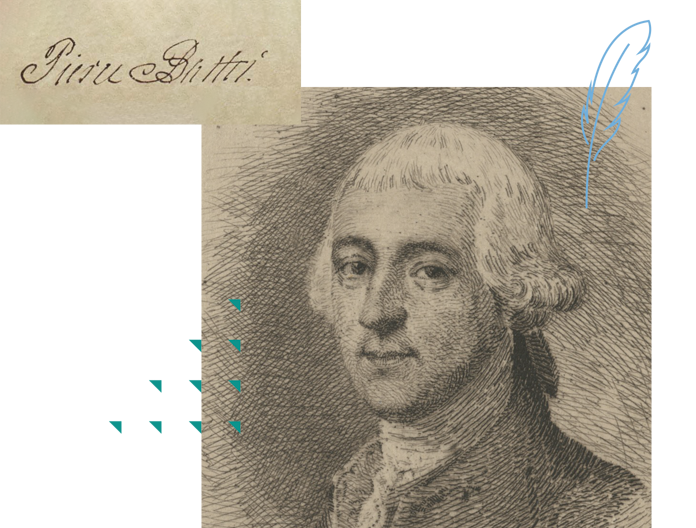

Pierce Butler | Signer of the Constitution

2:27

Biography

Pierce Butler was born in Ireland, the son of an aristocrat who was a member of Parliament and a baronet. As a younger son of the British aristocracy, Pierce Butler could not expect to inherit his father’s estate; this privilege belonged by law to the eldest son. Thus like many such young men, Butler chose a career in the military. He became a major in His Majesty’s 29th Regiment and was among the soldiers stationed in Boston in 1768 to quell disturbances there. But while in America, Butler married Mary Middleton, the daughter of a wealthy South Carolinian. He resigned his commission and began a new life as a Carolina planter.

When the Revolution began, Butler chose to support the American cause. He entered the military once again, but this time as an adjutant general in the South Carolina militia. His loyalty to his adopted land cost him dearly, for he lost most of his property and was reduced to borrowing money from a contact in Amsterdam.

Despite his financial problems, Butler was elected both to the Confederation Congress and to the Constitutional Convention. At the convention he proved himself an ardent and outspoken nationalist although, as William Pierce observed, Butler was not much of an orator. While a strong supporter of an empowered national government, Butler was also eager to protect the interests of his region. At the Convention, he introduced the Fugitive Slave Clause to protect slavery, and supported the prohibition of regulation of the slave trade for 20 years.

In the end, he was satisfied with the work of the Convention. In a letter to a relative in October of 1787, Butler downplayed the originality of the Constitution, explaining that it borrowed heavily from the political structures of Britain. “We, in many instances, took the Constitution of Britain, when in its purity, for a model, and surely We cou’d not have a better. We tried to avoid what appeared to Us the weak parts of Antient as well as Modern Republicks. How well We have succeeded is left for You and other Letterd Men to determine…”

Upon returning to South Carolina, he advocated for the Constitution, but he did not participate in the state’s ratifying convention. He did not think there was a danger that the Constitution would fail to be approved. As he told his relative Weedon Butler in March of 1788, “The Constitution I think will be agreed to, and be adopted tho’ it has some few opponents. Where is that work of man that pleases everybody!”

Butler’s political loyalty in the years that followed was erratic. He was sent to the Senate in 1789 as a Federalist, but he refused to support the party’s policies on several occasions. For example, although he supported Hamilton’s fiscal policy, he voted against the Jay Treaty and many of the Federalist judiciary and tariff positions. He seemed in the 1790s to have become a Jeffersonian, but this commitment failed when he decided the Jeffersonians had strayed from their principles. Butler had held out the hope that the nation would change its political “diet” by electing Jefferson in 1800, but he was disappointed. Jefferson’s administration, he declared, was “pork still with only a change of sauce.” In 1805 Butler resigned his Senate seat and devoted himself to the duties and pleasures of life as a wealthy planter. In this role, he prospered; by his death Butler owned more than a thousand enslaved people and an estate worth more than a million dollars.

In his later years, Butler moved permanently to Philadelphia where he had long owned a home that allowed him to escape the worst of South Carolinian summers. Philadelphia was also the home of his only married daughter Sarah, whose husband was a physician there. Butler died in February 1822 after an extended illness. He was 77 years old.