Summary

Philip Livingston was part of a large and politically influential family. He signed the Declaration, and then British forces took over his Brooklyn estate.

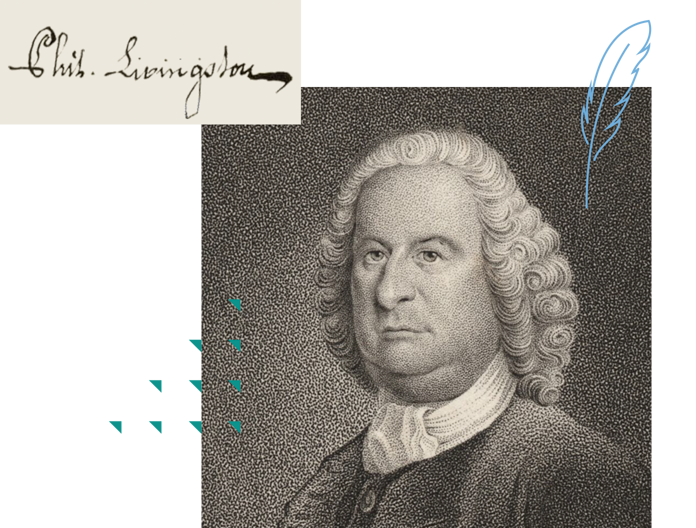

Philip Livingston | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:23

Biography

Philip Livingston was born in Albany, New York, the son of a Dutch mother, Catharine Van Brugh, and a father with Scottish roots. The Livingston family was large and politically-influential—including Philip’s cousin Robert R. Livingston, who served on the Committee of Five (but did not sign the Declaration), and Philip’s brother William, who became the first governor of New Jersey. Philip’s father and namesake owned a sprawling estate north of New York City and was known as the Lord of the Livingston Manor. Philip senior provided his son with the best education available in the colonies, sending him to Yale College in Connecticut. After his graduation, the younger Philip Livingston began an apprenticeship with his father, who was not only a farmer but a merchant. Philip’s ambition soon carried him to New York City, where he began a career in the import business. In his store, he sold a variety of imported goods, from black pepper to Bohea tea, to Jamaica rum and cheese, iron pots, hardware, glass, marble chimney pieces and furs. Among his shipping ventures was the transportation of hundreds of kidnapped Africans to New York as enslaved laborers.

Livingston established a reputation as a central figure in New York philanthropic circles. He played a critical role in the founding of King’s College [now Columbia University] and endowed a Professorship of Divinity at his alma mater, Yale. He also helped organize the New York City Public Library. At the same time, he entered the political sphere, serving first as an alderman for the East Ward of New York City and a delegate to the ill- fated Albany Congress in 1754. Beginning in 1759 he served in the colony’s provincial assembly and by 1768 he had become its Speaker.

Throughout the 1760s, as Britain redefined the relationship between the colonies and the Mother Country, Livingston hoped that a peaceful compromise between the two sides could be hammered out. In the meantime, he would participate in formal protest and in building a communications network among the colonies. But by 1774, he had given up hope that reconciliation was possible. In that year he agreed to represent New York at the Continental Congress. When Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence was approved, Philip Livingston stepped forward to sign it.

In the summer of 1776, the war with Britain came to New York City. General Washington’s army could not defend against the overwhelming military and naval force pitted against them and by the end of August the British occupation had begun. Britain would hold the city until the end of the Revolution in 1783. During this long occupation, Livingston’s Manhattan residence was used as a soldiers barrack and his Brooklyn estate was turned into a Royal Navy hospital. Philip and his family fled to their home in Kingston but the war followed them there. In October of 1777 the British burned this upstate city to the ground as punishment for allowing the constitution of the state of New York to be written and adopted there.

Philip Livingston was a senator at the first meeting of the new legislature created by this state constitution. At the same time, despite increasingly poor health, he continued to serve in the Continental Congress. By June of 1778, he was dead, a victim of the retention of fluid caused by heart failure or lung problems that the 18th century called “dropsy.”

Over the course of his life, Livingston had a reputation for being “somewhat irritable,” and a man who reserved his affection and tenderness for his family and closest friends. As one colleague described him, “There was a dignity, with a mixture of austerity, in his deportment, which rendered it difficult for strangers to approach him. He was silent and reserved, and seldom indulged with much freedom in conversation.” Small wonder that the loquacious and often argumentative John Adams did not like Livingston. Although Adams conceded that Livingston was a sensible man and a gentleman, “there was no holding any conversation with him. He blusters away.”