Summary

At the Constitutional Convention, John Rutledge was an influential figures as a moderate nationalist who looked out for the interests of the southern states. Rutledge later served on the Supreme Court.

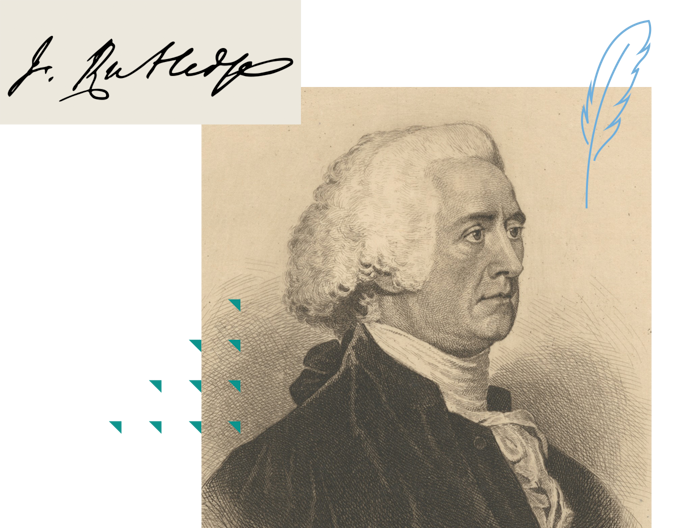

John Rutledge | Signer of the Constitution

2:52

Biography

John Rutledge was born into a large slaveholding family near Charleston, South Carolina, in 1739. His early education came from a triumvirate of his father, an Irish immigrant and a physician, an Anglican minister, and a hired tutor. In his teens, he was sent to London to study law at London’s Middle Temple, and by the age of 21, he was admitted to the bar in England. He then wasted no time returning to Charleston to establish a very successful legal practice and to enrich through the acquisition of plantation land and enslaved people. He married Elizabeth Grimke and moved into an elegant townhouse that would eventually accommodate his ten children.

Like many men of wealth, Rutledge entered the political world of his colony. In 1761, he was elected to the South Carolina Assembly and served until the war for independence began. As tensions had developed between the Mother Country and the colonies, Rutledge worked to preserve the self-government South Carolina enjoyed without severing its relationship with Britain. As the years passed, he recognized this was impossible. By 1774, he was a delegate to the First Continental Congress; in 1775, he served in the Second Continental Congress, and in 1776, he abandoned his hope of compromise and helped draft the state constitution. He accepted the presidency of the lower house of the legislature and helped steer South Carolina through the transition to independence.

Rutledge’s support for independence did not mean he supported democratic changes in the state government. He remained a social conservative. But he accepted the governorship in 1779, and led the state until the British military invasion of South Carolina forced the adjournment of the legislature and laid siege to Charleston. By May of 1780, the American army defending the city had been captured, the British took control of Charleston, and John Rutledge saw his property confiscated. Rutledge managed to escape to North Carolina, where he attempted to reclaim his state from the hands of the British. In 1781, General Nathanael Greene helped him achieve this goal. Although the state government was reestablished, Rutledge never fully recovered the money he lost during this period.

At the Constitutional Convention, he emerged as one of the most influential figures, a moderate nationalist who looked out for the interests of the southern states, including protections for slaveholders. In his character sketch of Rutledge, William Pierce acknowledged that the South Carolinian’s reputation in the Continental Congress had given him “a distinguished rank among the American worthies.” But although Rutledge was considered a fine orator in his home state, Pierce was not impressed. “In my opinion,” he wrote, “he is too rapid in his public speaking to be denominated an agreeable Orator.” Nevertheless, Rutledge could be effective when he opposed a proposal he thought unwise. When, for example, it was proposed that voting rights be reserved to landowners only, Rutledge objected. He saw that this would divide the people into “haves” and “have-nots,” and lead to the dangerous, lasting resentment of those denied suffrage. With Benjamin Franklin’s support, Rutledge prevented this proposal from being adopted.

Once the Constitution was ratified, John Rutledge focused some of his political energy on the federal arena. He was a presidential elector in 1789, and, in his first term as president, Washington appointed Rutledge as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. But in 1791, Rutledge abandoned that bench to become Chief Justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court. In 1795, Washington tried once again to place Rutledge on the U.S. Supreme Court, but the Federalist-run Senate refused to confirm the appointment. Their rejection, which effectively ended his public career, was likely the result of his public criticism of the Jay Treaty with England. Yet, it was compounded by Rutledge’s known lapses into mental illness and depression during the 1790s. These episodes were brought on by the sudden death of Elizabeth Grimke Rutledge in the summer of 1792, by the weight of financial problems, and by declining health.

John Rutledge attempted suicide in December of 1795 by drowning, but he was rescued by two enslaved African Americans. He resented their action, insisting that he had a right to dispose of his own life as he pleased. He attempted suicide a second time following the Senate’s rejection of his appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court. He died five years later in 1800 at the age of 60.