Summary

John Hart of New Jersey was severely critical of Britain’s attitude toward the colonies. Hart signed the Declaration, and his wealth was later diminished by the war.

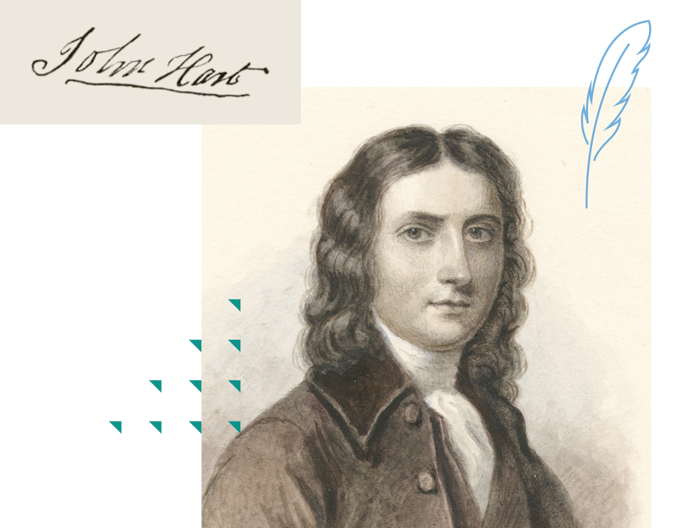

John Hart | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:22

Biography

John Hart was probably born in 1713 in Stonington, Connecticut, or Hopewell, New Jersey, and was the son of a farmer and justice of the peace Edward Hart. John had a minimal education, learning to read, write, and do what the 18th century called “figures” (that is, basic math). As a young man, he was thought to be quite handsome; his black hair and light eyes gave him a striking appearance.

In 1741, he married Deborah Scudder and soon began to acquire property in New Jersey. His first major purchase, in 1740, was 193 acres of land in Hopewell; by the 1770s, he was the largest landowner in town. His success led to public service as a justice of the peace, and, by 1761, he was a member of the Colonial Assembly. In 1768, despite no formal legal education, he was appointed to the Court of Common Pleas. Yet, like so many of the men who would sign the Declaration of Independence, Hart had become severely critical of the arc of Britain’s new attitude toward the colonies.

In 1774, he was elected to the New Jersey committee “to elect and appoint Delegates to the First Continental Congress, and to protest the Tea Act.” From this point onward, he became an open opponent of British rule. In 1775, he served on the colony’s Committee of Correspondence and the Committee of Safety, both radical steps toward independence. In 1776, he was elected one of five New Jersey delegates to the Second Continental Congress. He arrived in Philadelphia in June, a proponent of independence. He signed the Declaration and then left in late August to become the speaker of the newly-created New Jersey General Assembly.

When the British advance reached the vicinity of Hart’s farm in December 1776, Hart’s role as Speaker to the General Assembly made him a target. He had to flee and hide for some time while his farm was raided by the enemy. Then, in June 1778, he took the risk of inviting the American army to camp on his farm. Washington brought 12,000 men with him, and they remained on Hart’s land until the last week in June. Four days after they left on June 24th, Washington’s well rested army fought and won the Battle of Monmouth.

On November 7, 1778, Hart returned home from a session of the Assembly in Trenton. Two days later, he revealed that he was too ill with “gravel” – the 18th century term for kidney stones—to return to the session. For six months, he was in pain until, on May 11, 1779, at the age of 65, John Hart died.

Hart’s wealth had been greatly diminished by the war. At his death, his property had to be sold off to pay his debts. But he was honored for his sacrifices for the Revolution. In his obituary, he was described as a “faithful and upright patriot in the service of his country.” He was remembered in a book in 1977 by an owner of Hart’s homestead. “Far from a legend,” he said of Hart, “he was a very human being . . . a capable, personable, ambitious, yet dedicated man . . . essentially conservative but heroically liberal . . . .” He was, this author declared, “a self-made man in his time.”