Summary

Hugh Williamson was the surgeon-general of North Carolina’s troops during the Revolutionary War. Williamson served on five committees at the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

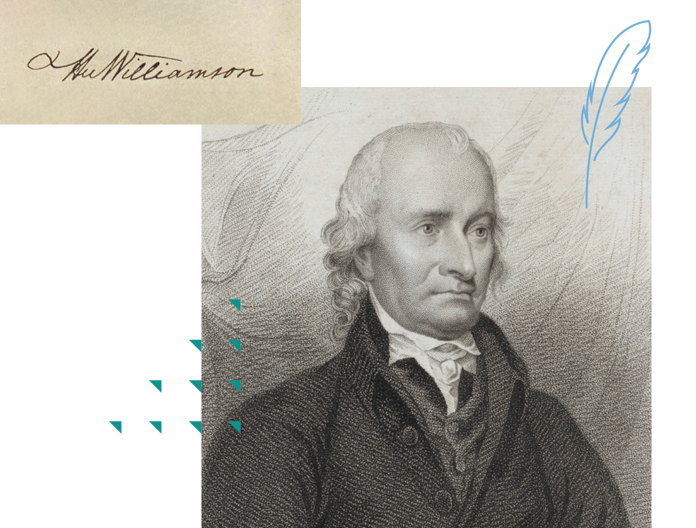

Hugh Williamson | Signer of the Constitution

2:35

Biography

Hugh Williamson, the eldest son of a Pennsylvania clothier, was born in 1735. His original ambition was to become a Presbyterian minister and toward this end his parents provided him the appropriate education. He went to preparatory school in Delaware and then to the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania) from which he graduated in 1757. Although he did become a licensed preacher he never received ordination. Instead, he became a professor of mathematics at his alma mater.

In 1764, Williamson made another career change. He decided to go to Europe to study medicine. He eventually won his degree in medicine from the University of Utrecht but after returning to America he discovered that practicing medicine was not the same as studying it. Instead, he found medicine emotionally taxing and sought relief by pursuing other scientific interests.

In 1773, while the colonies inched closer to independence, he made a fund-raising trip to the West Indies and Europe to help create an academy in Newark, Delaware. This trip began from Boston where he actually witnessed the Boston Tea Party. After arriving in London, he was asked to testify to the destruction of the tea before the British Privy Council. Although he had participated in no political protests against British policies, Williamson was astute enough to gauge American discontent. He warned the British officials that a rebellion would take place if they continued to tax Americans.

Williamson unwittingly—or thoughtlessly—contributed to this march toward rebellion. While in England, he became friendly with Benjamin Franklin who was then serving as an agent for the American colonies and hoping for a way to bring a reconciliation between the Mother Country and colonists. Williamson, however, added fuel to the fire by providing Franklin with the letters written by Boston-born Governor Thomas Hutchinson in which the governor expressed hope that the British would send more troops to suppress colonial protest.

Williamson published a pamphlet called “The Plea of the Colonies” in 1775. In it he asked the Whigs, or liberals, in Parliament to support the American colonists. While this seemed to commit Williamson to that cause, he was still traveling around Europe when independence was declared. When Williamson finally returned to America, he did not reestablish his medical practice in Philadelphia. Instead, he settled briefly in South Carolina. He then moved to Edenton, North Carolina where he combined a new career as a merchant in the West Indian trade with a renewed interest in medicine.

It was during the Revolution that Williamson made his commitment to the American cause. Working as the surgeon-general of North Carolina’s troops, he was often required to cross British lines to care for the wounded and preserve the health of the soldiers by attending to their hygiene.

Despite his patriotic medical service, Hugh Williamson did not seek any political office until the revolution was over. In 1782, he won election to the lower house of the North Carolina legislature and served in the Confederation Congress for three years. In 1787, he joined four colleagues as the state delegation to the Constitutional Convention. Here he served on five committees, including the critical committee, known variously as “the Committee on Postponed Matters” or “the Committee of Eleven,” “or the Committee on Postponed Parts,” that was formed to resolve issues still pending on security, presidential election and repayment of war debts. When the Convention ended, Williamson signed his name to the Constitution.

Williamson commented on the new plan of government he had helped create. “If I might express my particular sentiments on this subject,” he wrote, “ I should describe it as more free and more perfect than any form of government that has ever been adopted by any nation; but I would not say it has no faults. Imperfection is inseparable from every device.” During the debates over ratification, he argued that Americans “have a common interest, for we are embarked in the same vessel….If there is any man among you that wishes for troubled times and fluctuating measures…this Government is not for him…. And if there is any man who has never been reconciled to our independence, who wishes to see us degraded and insulted abroad, oppressed by anarchy at home, and torn to pieces by factions…this Government is not for him.”

Williamson’s staunch support for ratification did not prevent him from voicing harsh judgment on the men who had written that Constitution. Writing to John Gray Blount on June 3, 1788, he evaluated the men of different regions of the new country. “You may have been taught to respect the Characters of the Members of the late Convention. You may have supposed that they were an assemblage of great Men. There is nothing less true. From the Eastern States there were Knaves and Fools… from the States Southward of Virginia They were a parcel of Coxcombs and from the middle States Office Hunters not a few.”

In 1789, Williamson was elected by North Carolinians to the inaugural U.S. House of Representatives, serving two terms in that office. But in 1793, he picked up stakes and moved to New York City eager to abandon politics to pursue literary and philanthropic interests. Over the next decades he published works on education, economics, history, and science, and he served as a trustee of three universities. In 1819, the 83 year old Williamson died suddenly while driving his carriage.