Summary

Gouverneur Morris attended the Continental Congress, and he later played an important role at the Constitutional Congress of 1787 where he served on multiple committees.

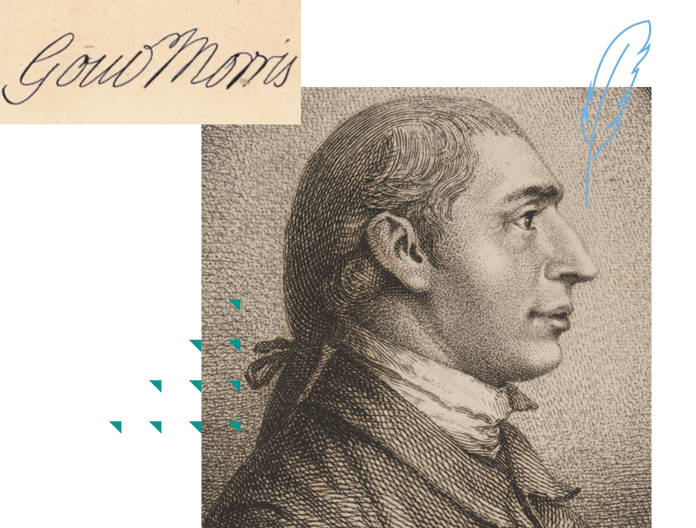

Gouverneur Morris | Signer of the Constitution

5:23

Biography

Gouverneur Morris was born in New York in 1752, into a family known for its wealth and public service. He was educated by private tutors and then went on to King’s College (later Columbia University) and graduated at the age of 16. He went on to study law and was admitted to the bar at 19. As an adult, Morris carried the scars of at least two accidents. As a teenager he dropped a kettle of boiling water, scalding his right arm and side and fortunately avoided losing his arm; as an adult in his late twenties, he suffered a carriage accident that left him with a mangled left ankle and several broken leg bones. His regular doctor was out of town, and the physicians available persuaded him that amputation was necessary. Despite the loss of the lower part of his leg, Morris continued to ride horses, shoot river rapids and dance. And, more remarkably, his peg leg did not deter him from gaining a well-earned reputation as an American Casanova. Nor did his physical appearance overshadow his intellectual gifts or his oratorical powers.

Morris showed an interest in politics just as tensions between Britain and the colonies emerged. Despite his fears that the protest movement against Parliament’s taxation policies and trade regulations would devolve into mob rule, and despite the support for Britain by family members and elite friends, by 1775 Morris had thrown in his lot with the Americans who would soon press for independence. He signaled his political choice by taking a seat in New York’s revolutionary provincial congress from 1775 to 1777. After the Declaration of Independence was signed, he joined John Jay and Robert R. Livingston in drafting the first constitution turning New York into a state rather than a colony.

Morris held a seat in the state legislature in 1777-78 and in 1778, attended the Continental Congress. At 26 he stood out as one of the youngest and most brilliant of the congressional delegates. But signs of Morris’s growing nationalism clashed with Governor George Clinton’s equally strong commitment to state sovereignty and in 1779, the Clinton faction forced the defeat of Morris’s bid for reelection to the Continental Congress. In response Morris relocated to Philadelphia where he rebuilt a successful legal practice and began to pursue business enterprises as well.

In 1781, he was ready to reenter politics. For the next four years he served as the main assistant to Robert Morris, then the superintendent of finance for the United States. [The two men shared a last name but were not related]. When the call went out for a constitutional convention, both Robert and Gouverneur Morris were among the 8 men chosen to represent Pennsylvania. But if Robert Morris was virtually silent during the debates that began in May, Gouverneur Morris was a leading figure at the convention. He spoke 173 times, taking the floor more often that the two other dominating figures, James Madison and James Wilson. He often interjected wit and sarcasm into his comments supporting an empowered new government. Although he did not hide his preference for a government populated by the elite while Wilson pressed for popular control of the legislative branch, the two men worked well together as they shaped the key elements of the constitution. And despite his conviction that aristocrats ought to govern, he spoke openly against slavery, viewing it as a curse on the states where it prevailed.

Morris served on multiple convention committees, including the important Committee on Postponed Matters. And, from his position on the Committee of Style, he took on the actual drafting of the constitution. It was Morris who perfected the Preamble to the constitution that made clear the benefits it held out for his countrymen.

In his sketch on Morris, William Pierce recognized the man’s brilliance, calling him “one of those Genius’s in whom every species of talents combine to render him conspicuous and flourishing in public debate.” Pierce viewed with awe Morris’s debate skills, writing “He winds through all the mazes of rhetoric, and throws around him such a glare that he charms, captivates, and leads away the senses of all who hear him. With an infinite streach [sic] of fancy he brings to view things when he is engaged in deep argumentation, that render all the labor of reasoning easy and pleasing.” Yet though he conceded that “No Man has more wit—nor can any one engage the attention more than Mr. Morris,” Pierce proved he was not blind to Morris’s flaws. “He is fickle and inconstant, never pursuing one train of thinking .”

In 1814, Morris explained his steamrolling strategy at the convention. Writing to Timothy Pickering he said , “My faculties were …to further our business, remove impediments, obviate objections, and conciliate jarring opinions.” If the convention were held in 1814, he assured Pickering, his strategy would be the same. “My sentiments and opinions,” he declared, had “undergone no essential change in forty years.”

After the constitution was ratified, Gouverneur Morris served as Minister Plentipotentiary to France where he engaged in dalliances with married French women and observed with horror the French Reign of Terror, a fate he believed America had avoided by adopting the constitution. He returned to the US in 1798 and won election to the Senate in 1800. However, he lost this seat after Jefferson’s Republican party took control of the government.

After his term in the Senate ended, Morris purchased the family estate Morrisania from his older brother and moved home to New York. For his remaining years he devoted his energies to investments in enterprises like the creation of the Erie Canal. His last public action was to support the Hartford Convention called by New England Federalists to protest the War of 1812. Here he went so far as to suggest succession and the creation of a separate New England-New York Confederation

At the age of 57 Gouverneur Morris at last became a husband. His wife, Ann Cary Randolph of Virginia had been accused of murdering a newborn baby said to be hers and her brother in law’s. Driven out of Virginia, she moved north and found employment as Morris’s housekeeper. Contemptuous of the rumors of infanticide spread by Virginia Randolphs, Morris married her on Christmas Day in 1809.

They lived happily together until he died in November 1816 from internal injuries and an infection caused by his decision to use a piece of whale baleen as a catheter to clear a blockage in his urinary tract.