George Mason drafted Virginia’s Declaration of Rights. He spoke frequently at the Constitutional Convention, but declined to sign the document over fears of an aristocracy or monarchy.

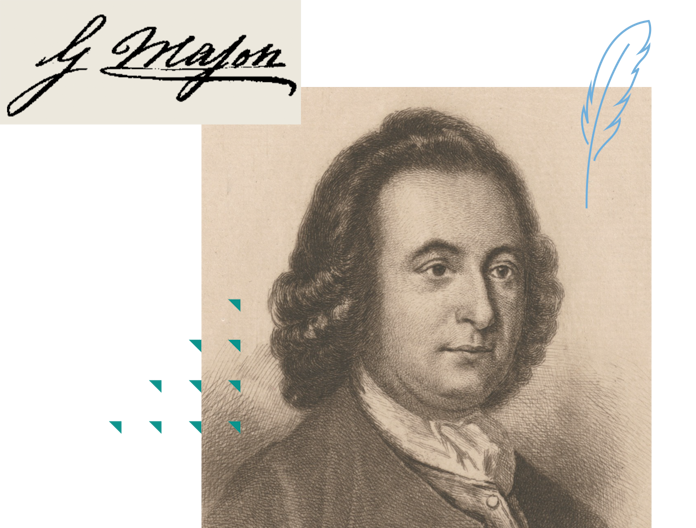

George Mason | Did Not Sign The Constitution

4:22

Biography:

George Mason was born into Virginia’s planter aristocracy in 1725. His father died in 1735 when a storm capsized the boat he was sailing across the Potomac River. Nine-year-old George was brought up by his uncle, John Mercer, whose vast library provided Mason with an informal legal education.

Mason’s mother managed the family’s vast estate until George came of age. In 1750, Mason married and built an impressive home which he named Gunston Hall and settled into a privileged country life. As one of the wealthiest planters in Virginia, he had a clear path to political office and community leadership. He served as justice of the Fairfield County court and became a trustee of the City of Alexandria between 1754 and 1779. He was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1759. Like many of his wealthy neighbors, Mason became a land speculator, investing in western lands through the Ohio Company until the Crown revoked the company’s right to operate in 1773.

In 1765, Britain signaled a change in policy toward the colonies by enacting the Stamp Act, the first direct tax on the Americans. Mason penned an open letter expounding the colonists’ position in order to win the backing of a committee of London merchants. The letter signaled his own approval of the emerging anti-British politics that would end in a revolutionary war. In 1774, he helped draft the Fairfax Resolves that delineated the constitutional basis for colonial opposition to the Boston Port Act. Then in 1776, he drafted Virginia’s Declaration of Rights which acted as a model for Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, and later as the groundwork for the Bill of Rights.

Between 1776 and 1780, Mason was involved in the transformation of Virginia from a colony to a state. He served in the House of Delegates of the Virginia General Assembly, but refused to go beyond local politics by attending the Second Continental Congress. In 1787, however, he agreed to serve as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. There, he was one of the most frequent speakers and was influential in shaping the Constitution. But when it came time to sign the Constitution, George Mason refused.

What had prompted his refusal? Mason thoroughly explained his reasons. First and foremost was the lack of a bill of rights. His other complaints included his belief that the House of Representatives was not representative of the nation, that the Senate was too powerful, and that the federal judiciary could overcome the state judiciaries and make justice unobtainable for ordinary citizens. In the end, Mason feared the new government was likely to become a brutal aristocracy or monarchy. Although Mason was skewered in the press for his refusal to endorse the Constitution, he held firm to his beliefs. William Pierce recognized Mason as a man of strong convictions, firm in his principles and in this, he was correct. Decades after the convention, James Madison echoed Pierce’s admiration for Mason’s adherence to his principles. “The objections which led him to withhold his name from [the Constitution],” Madison wrote in 1827, “have been explained by himself. But none who differed from him on some points will deny that he sustained throughout the proceedings of the body the high character of a powerful reasoner, a profound statesman, and a devoted Republican.”

Madison would satisfy Mason’s desire for a bill of rights soon after the first U.S. Congress met. Although Mason predicted that any amendments to the Constitution would be little more than “Milk & Water Propositions,” he was gratified to see the final Bill of Rights. These ten amendments were ratified in 1791, a year before George Mason died, a victim of gout and possibly pneumonia.