Summary

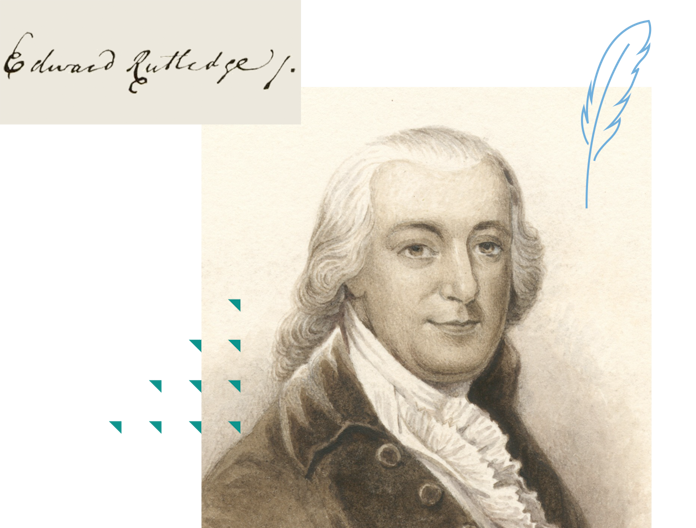

At 26, Edward Rutledge was the youngest signer of the Declaration of Independence. He persuaded South Carolina to support independence after first opposing it.

Edward Rutledge | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:39

Biography

Edward Rutledge was born in South Carolina in 1749. Edward was the youngest of the seven children of Dr. John Rutledge and Sarah Hext Rutledge. Edward’s father was an Irish immigrant who became not only one of the first men to practice medicine in his parish but also a wealthy owner of land and slaves.

As the son of a member of the colony’s elite, Edward received a classical education, first from his father and later from a tutor. In 1772, he followed two older brothers to England where he continued his studies at Oxford University. He then studied law at the Inns of Court in London and was admitted to the English bar in 1772 at the age of 23. The next year, he returned to South Carolina and entered into a profitable law practice with fellow South Carolinian Charles Cotesworth Pinckney.

Rutledge quickly earned a reputation as a gifted orator and a talented attorney. At the age of 24, he successfully defended a printer who had been imprisoned for printing an article critical of the members of the upper house of the province’s royal government. By 1774, he had acquired a plantation, 50 enslaved men and women, and a wife, Henrietta Middleton. Like most members of the Southern planter elite, he married within the small and tight circle of his social class. Henrietta was the sister of Arthur Middleton, another South Carolinian who would sign the Declaration of Independence.

Rutledge entered the political arena while still in his twenties. He served as a delegate to the Continental Congress for the critical years of 1774 to 1776, and also as a state legislator from 1775 to 1776. Serving with him was his older brother John, also a lawyer and landowner, and his brother-in-law, Arthur Middleton.

Rutledge was not a social radical. In fact, during the Revolution, he would work to have African American soldiers expelled from the Continental Army. Nor was he, at first, a political radical, for he hoped for a reconciliation with Britain that would preserve colonial rights. In his diary, John Adams credited himself with persuading the South Carolina delegation to the Continental Congress to support the growing move for independence, but Rutledge remained unconvinced of the wisdom of this course of action. When, on June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee’s motion, “Resolved, that these united colonies are, and of right ought to be free and independent states,” was introduced, Rutledge stood firmly against Lee and with those he called “the sensible part of the house.”

Writing to New Yorker John Jay, Rutledge explained the position he, and men like John Dickinson, Robert R. Livingston, and James Wilson were taking: “No reason could be assigned for pressing into this measure, but the reason of every Madman, a shew of spirit….” In short, neither Rutledge nor his colleagues from South Carolina would take part in what they considered a foolish show of bravado.

Yet on July 1st, when the South Carolinians voted “no,” it was Rutledge who persuaded them to support the independence resolution. On July 2, their no became a yes. At 26, Rutledge was the youngest signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Rutledge was next appointed to the committee to draft the country’s first constitution. He proved wary of giving this government too much power for he feared it would be dominated by New Englanders. Writing again to John Jay, he declared that “if the Plan now proposed should be adopted nothing less than Ruin to some Colonies will be the Consequences of it.” He favored the protection of “provincial distinctions ,” especially the institution of slavery.

In November of 1776, Edward Rutledge took a leave from Congress to join in the defense of South Carolina. He fought in several battles against the British army in the Charleston Battalion of Artillery and became a captain. He also took a seat in the state’s House of Representatives where he focused on military preparedness and on imposing harsh sanctions against those loyal to the Crown.

The state sent him back to Congress in 1779, but he took a leave once again in 1780 as the British mounted a third invasion of South Carolina. This time, he was captured by the enemy. The British granted him parole, but soon arrested him again, this time for allegedly plotting with other Charleston residents to organize resistance to the occupying enemy. He was held prisoner in St. Augustine, Florida, and his property was seized. He was freed in a prisoner exchange in July 1781.

The following January, he returned to the state government, serving in its House of Representatives for the next thirteen years. During these postwar years, he worked to promote the economy of his war-torn state.

In 1788, he was a leader in the state ratifying convention, supporting the adoption of the Constitution but also endorsing proposed amendments to it. On two occasions, the country’s first president, George Washington, asked Rutledge to serve on the nation’s Supreme Court, but Rutledge declined.

His personal health was fragile and the loss of his wife in 1792 was a blow, although he married again that year. In 1796, he began a term in the South Carolina Senate and in 1798, he was elected governor.

He died in office in January 1800, after suffering a stroke. He was only 50 years old.