Edmund Randolph introduced the Virginia plan at the Constitutional Convention, then declined to sign the Constitution due to concerns about a chief executive and the amendment process.

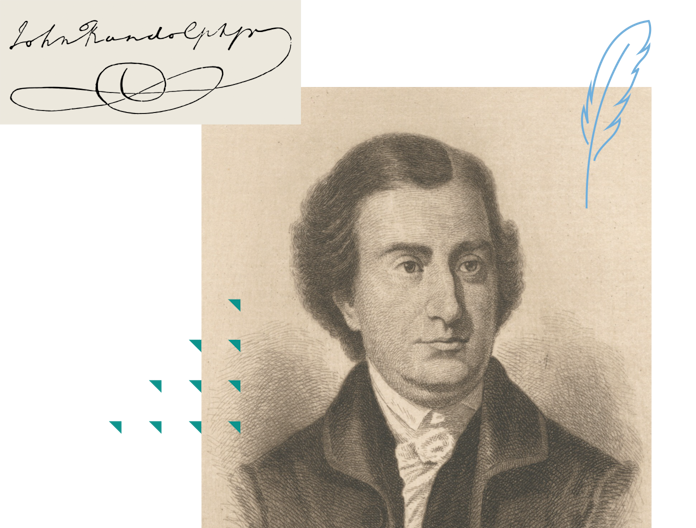

Edmund Randolph | Did Not Sign Constitution

4:01

Biography:

Edmund Randolph was born in 1753, the son of John Randolph and Ariana Jenings. As a child of one of the leading families in Virginia, he was well educated, first at the College of William and Mary and in the study of law with his father and his uncle, Peyton Randolph. He came of age as the Revolution approached and broke with his father over which side to support. John Randolph went to England with the royal governor; his son enlisted as an aide-de-camp to General Washington in 1775.

The young Edmund Randolph was twenty-three when he entered politics and his rise was rapid. In 1776, he attended the convention that adopted Virginia’s first state constitution. Soon afterward he was elected the state’s first Attorney General and the Mayor of the state capital, Williamsburg. In 1779, he was sent to the Continental Congress and by 1786, the 33 year old Randolph became Governor of the state. When he resigned the governorship in 1788 it was because he wished to play a role in the state legislature as it shaped Virginia’s legal code.

In 1786 Randolph had attended the Annapolis Convention, a forerunner of the convention in Philadelphia. When the delegates gathered in Philadelphia, he joined George Washington, George Mason, James Madison, and George Wythe at Virginia’s table. Four days after the Convention was called to order, Randolph rose to present the Virginia Plan. This plan was drawn up by James Madison, but Madison saw the wisdom in having the tall, handsome Randolph, whose “harmonious voice” William Pierce admired, present it to the convention. The Virginia Plan would replace the Articles of Confederation government with a powerful central government comprised of legislative, judicial, and executive branches. This structure was far from novel; the tripartite division was familiar and existed in the British government, in most of the colonial governments and the new state governments. But the power of the proposed government would diminish the autonomy of the states since the federal legislature would be given the power to veto state laws and to use force against any state that failed to fulfill its duties. The convention would reject the right of the new government to use force against the states, and it would reject the legislature’s power to veto state laws, but, on the whole, the Virginia Plan became the blueprint for the new Constitution.

Although he had introduced the Virginia Plan to the delegates, Randolph was ambivalent about it. He agreed that the Articles of Confederation was inadequate to the needs of the new nation, but he was uncertain if he could support the strong central government the Convention was designing. Although he sat on the Committee of Detail that prepared a draft of the Constitution, he refused to sign off on it when they were done. His doubts centered on the creation of a single executive, which he feared would lead to monarchy. He also worried that the amendment process being proposed would make it difficult to correct the flaws contained in the Constitution. When it came time to sign the Constitution, Edmund Randolph’s name was absent. Yet when Virginia’s ratifying convention met, Randolph was a strong and persuasive advocate for its adoption.

Randolph knew that he would be accused of hypocrisy given his apparent reversal of his position on the Constitution. He defended his change of heart during this state convention, citing both substantive concerns and practical political realities. “The suffrage which I give in favor of the Constitution, will be ascribed by malice to motives unknown to my breast…Lest…some future annalist should in the spirit of party vengeance, deign to mention my name, let him recite these truths, -- that I went to the federal convention with the strongest affection for the union; that I acted there in full conformity with this affection; that I refused to subscribe because I had, as I still have, objections to the constitution and wished a free enquiry into its merits; and that the accession of eight states reduced our deliberations to the single question of union or no union.”

President Washington drew Randolph into his administration by making him Attorney General of the U.S. Randolph tried to stay neutral as Jefferson and Hamilton locked horns over the policies and programs the new government ought to embrace but this remained difficult. When Washington called on him to become Secretary of State after Jefferson resigned, neutrality seemed impossible. When he opposed the Jay Treaty, Randolph lost Washington’s support and in 1795, he left office and sought a less conflicted life as a Virginia lawyer. He was warmly greeted at home by the members of Virginia’s planter elite.

During his retirement from legal practice, Randolph wrote a history of Virginia. In 1807, he returned briefly to the courtroom to defend Aaron Burr in his treason trial. But by 1813, he was suffering from paralysis, and he died on a visit to a friend’s estate. He was 60 years old.