Summary

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney was a loyal Federalist and he was a leading nationalist at the Constitutional Convention. Pinckney later served as Minister to France and ran for President.

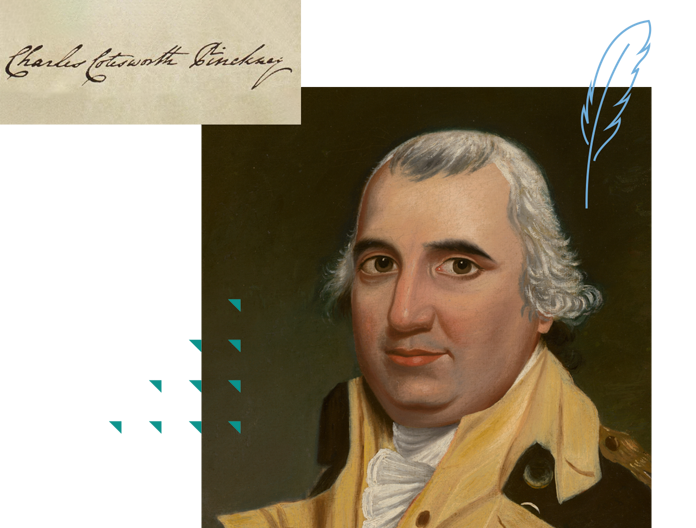

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | Signer of the Constitution

4:23

Biography

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney was born to a slaveholding family in South Carolina in 1746. His mother, Eliza Pinckney, was well known as the Carolinian who introduced the profitable crop of indigo to her colony, and his father was a well-established political leader.

When Charles was seven years old, he made the transatlantic trip to England with his father who had been appointed as South Carolina’s colonial agent. In London, the young boy studied with a tutor, then attended preparatory schools, and finally went on to study at Oxford where he attended lectures by the famous legal scholar William Blackstone. After graduation, he went on to train as a lawyer at the Middle Temple. Although he was admitted to the English bar in 1769, 23-year-old Pinckney decided to spend time touring Europe and studying chemistry and botany with leading lights in the scientific fields. By the time he sailed home later that year, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney had received a rare education even for members of the colonial elite.

Pinckney returned to his home colony at the end of 1769 to set up his legal practice. His family background and his educational credentials paved the way for his entrance into politics, and he was immediately elected to the provincial assembly. He embraced the American cause before independence was declared, and, by 1776, he was a member of the local committee of safety and was serving on the committee assigned to draw up the plan for an interim government of South Carolina.

When the war began, Pinckney turned from politics to military service. He immediately joined the First South Carolina Regiment as a captain and rose in rank during the fighting both in the South and in the North. When Charleston fell to the British in 1780, Pinckney was taken prisoner, and he was not released until 1782. While he was held by the British, he asserted his patriotism, declaring, “If I had a vein that did not beat with the love of my Country, I myself would open it. If I had a drop of blood that could flow dishonorable, I myself would let it out.”

Free once more, and honorably discharged from his state’s military, Pinckney returned to Charleston to resume his law practice. By 1778, he was once again in government, serving first in South Carolina’s Assembly and then in its Senate. Together, Charles and his brother Thomas wielded considerable political power as spokesmen for the interests of the landed elite. He opposed the efforts of his close friend Edward Rutledge to end the importation of slaves into the state, arguing that an economy based on rice production needed a steady infusion of new laborers.

In 1787, Pinckney was chosen as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. There, he emerged as a leading nationalist, joining Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, James Wilson, and Gouverneur Morris in advocating an “energetic government.” Because he assumed the Senate would be a house occupied by members of the American elite, Pinckney lobbied unsuccessfully for a requirement that Senators serve without pay. He was more successful in his support of the Senate’s role in ratifying treaties.

During the South Carolina debate over ratification of the Constitution, Pinckney defended the Framers’ decision not to add a Bill of Rights. Since such bills usually begin with a declaration that all men are by nature born free, he thought it hypocritical, or as he put it, “with a very bad grace,” to include such a claim when so many men in the new country were born as slaves.

Pinckney was a firm Federalist, but, until 1796, he declined to hold a position in the new government. In that year, as tensions increased between the French and the United States, he accepted an appointment as Minister to France. Although he hoped to negotiate a détente with the French, the French government insulted him by refusing to receive his credentials. The next year, he agreed to serve as a member of a three-man commission charged with restoring relations with France. This time, the French demanded money before they would enter into any negotiations with the American diplomats. Pinckney, now twice insulted, was defiant. “No! No! Not a six pence!,” he declared. The treatment of the American commissioners in what came to be known as the “XYZ Affair,” prompted President Adams and the Federalist Congress to prepare for war with France.

Pinckney returned to military service when he arrived home in 1798. He served as a major general in charge of American forces in the South until 1800 when a new treaty with France ended the threat of war. By that time, the Republican Party, organized by Madison and Jefferson, had come to power. Pinckney remained a loyal Federalist and ran for President under his party’s banner in 1808. He won only 14 electoral college votes, not even carrying his home state. The Republican ascendancy had ended his career on the national stage.

After his defeat, Pinckney devoted his time and energies to his legal practice, to service in his state legislature, and to philanthropy. He died at the age of 79 in 1825. On his tombstone were these words: “One of the founders of the American Republic. In war he was a companion in arms and friend of Washington. In peace he enjoyed his unchanging confidence.”