Summary

Charles Carroll did not hesitate to sign the Declaration despite the risk to his enormous wealth. He was the only Catholic whose name appears on the document.

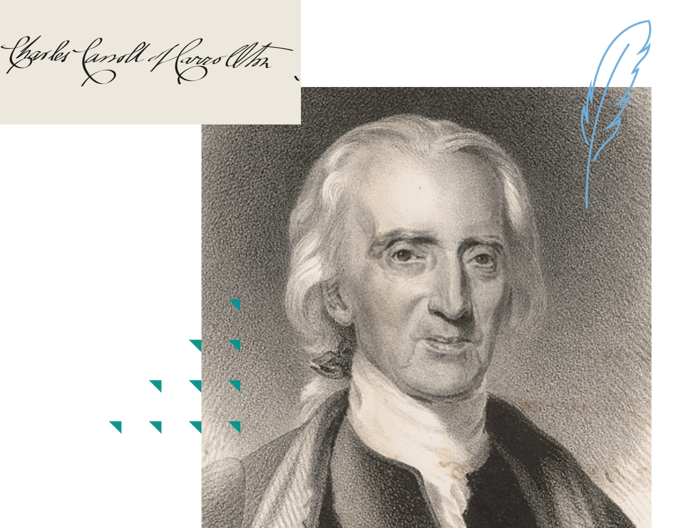

Charles Carroll | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:25

Biography

Born in Annapolis, Maryland, Charles Carroll was the only son of Charles and Elizabeth Brook Carroll. He was the third in his family to carry the name, and, to distinguish him from his father, he would be referred to as Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

His father was a prominent member of the gentry and a fierce advocate for Catholic equality. He sent his son to Europe when he was only eleven years old to receive the Catholic education that would be denied to him by Maryland law. In France, the boy attended several prestigious universities, but he crossed the English channel to study law. In London, Charles witnessed the shift in British attitudes and policies toward the American colonies. When he returned home at the age of 28, he found the colonists growing alienated from their Mother Country.

In 1768, Charles married a distant cousin, Mary Darnell, but both she and his father died fourteen years later in 1782. His father’s death made him heir to a vast agricultural estate that made him the wealthiest man in the colonies. His manor, Carrollton, was a 10,000-acre estate that housed about 300 enslaved workers.

Carroll was barred from political office by his religion, but he could not be prevented from giving voice to the growing mistrust of Britain and its colonial officers. In 1773 , he wrote a series of public letters under the pseudonym “First Citizen” opposing the royal governor’s imposition of fees for office holding and warning that this was a step toward tyranny. His opponent in this exchange of views was Daniel Dulany, son of a powerful political father of the same name and a loyal supporter of the Crown. During their debate, Dulany resorted to ad hominem attacks. Carroll responded with restraint, noting that Dulany turned to “virulent invective and illiberal abuse” when his arguments failed. Many of his fellow Marylanders agreed with Carroll. He was on his way to becoming a leader of Maryland’s independence movement.

Carroll was apparently blunt in his opposition to Britain’s colonial policies. In 1774, when Boston held its famous tea party, Carroll was asked for advice on how to deal with the British vessel arriving in Chesapeake Bay with the hated tea. He is said to have answered, “Gentlemen, set fire to the vessel and burn her, with her cargo, to the water’s edge.”

In 1775, Carroll broke through the religious barrier to become a member of an anti-British Committee for Public Safety. This marked the first time since 1715 that a Catholic had held a public office in Maryland. In 1776, he was elected a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. Although he arrived in Philadelphia too late to vote in favor of the Declaration of Independence, he did not hesitate to sign it despite the risk to his enormous wealth. He was the only Catholic whose name appears on the document.

Carroll remained in Congress until 1778. He served on the war board, charged with finding supplies for the American army. In 1778, he returned to Maryland and helped in the drafting of the state’s constitution. He also continued to break barriers as a Catholic by his election to the state senate in 1781 and later to the U.S. Senate. When Maryland passed a law forbidding a man to serve in both the state and federal government, he resigned from the U.S. Congress, preferring to serve in his state government. He continued in the Maryland Senate until 1800.

In 1800, Charles Carroll lost reelection and retired from politics. He devoted his energies to the building of infrastructure, including railroads and canals, and to the establishment of the First and Second National Banks. He honored his faith by funding the construction of a church basilica in Frederick, Maryland, and providing funding for the creation of Georgetown University, a Catholic school of higher learning.

Carroll died in 1832 at the age of 95, having outlived four of the five first U.S. presidents. His contribution to independence and to the war effort was honored in the third stanza of a state song, “Maryland, My Maryland”: “Thou wilt not cover in the dust / Maryland! My Maryland! / Thy beaming sword shall never rust / Maryland! My Maryland! / Remember Carroll’s sacred trust / Remember Howard’s warlike thrust / And all thy slumberers with the just / Maryland! My Maryland!”