Summary

Carter Braxton of Virginia signed the Declaration of Independence, but he was sent home from Congress after criticizing John Adams in a pamphlet.

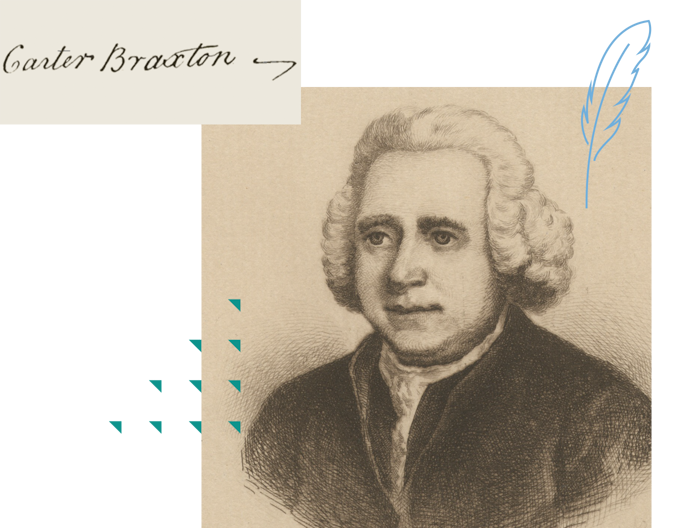

Carter Braxton | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:15

Biography

Carter Braxton was the younger of two sons of George and Mary Carter Braxton. He was born at Newington, the Virginia estate of his grandfather, a prosperous merchant, planter, and slaveholder. His mother, who died seven days after giving birth to him, was the youngest daughter of the fabulously wealthy Robert “King” Carter, whose name Braxton carried.

Braxton married at the age of 19 while still a student at the College of William and Mary. His bride, Judith Robinson, was the niece of the powerful speaker of the House of Burgesses. Sadly, she, like his mother, died giving birth only two years later. Braxton, mourning her loss, set sail for Europe, where he remained for two or, perhaps, three years. In 1760, he married once again, this time to Elizabeth Corbin, daughter of a member of the Royal Governor’s Council. Carter and Elizabeth had ten sons and six daughters. Elizabeth outlived her husband by 17 years.

When his older brother died in 1761, Carter Braxton inherited the remainder of the family estate. But both brothers had lived extravagantly, and Carter found himself burdened with large debts. Although he had to sell land to satisfy some of his creditors, he still owned a vast estate of more than 12,000 acres and held 165 enslaved people.

As a member of the landed elite of Virginia, Braxton was expected to hold public office. Early on, he served as justice of the peace and a parish sheriff. He was then elected in 1761 to the House of Burgesses and served most terms until 1775. He proved to be far more conservative than many of his colleagues, although he did support the nonimportation of British goods in 1769.

By 1775, Parliament’s policies drove Braxton into the opposition camp. Still, he strongly opposed Patrick Henry’s radical tactics in protesting the policies of the Royal Governor, Lord Dunmore. Henry, leading a band of volunteer militia men, marched on Williamsburg to protest the royal governor’s seizure of the colony’s gunpowder. Braxton averted the crisis by pledging to have the powder paid for out of his father-in-law’s account. But if he prevented a violent confrontation, he also made an enemy of Henry for years to come.

Braxton may not have been ready for a break from Britain, but he agreed to serve on Virginia’s Committee of Safety, which oversaw the necessary preparations for war. Then, in early 1776, he took his seat in the Continental Congress. There, he resisted the obvious sentiment for independence.

Writing in April 1776, he observed that “Independence is in truth an elusive bait which men inconsiderably [sic] catch at, without knowing the hook to which it is affixed.” He was also wary of republics, which he noted often came to unhappy ends. A republic’s advantages “existed only in theory and were never confirmed by the experience, even of those who recommend it.” Yet, by July, he had accepted the need for separation from Britain, and he supported Lee’s motion and signed the Declaration of Independence. Still, he could not embrace what he considered the radically democratic ideas of men like John Adams. When he published a pamphlet challenging Adams’s views, Congress sent him home.

Carter Braxton returned to Virginia in the Autumn of 1776. The Revolutionary War that followed left him financially ruined, but he continued to serve in government, taking a seat in the newly created legislature known as the House of Delegates. He served for almost ten years in that office, chairing several important committees. In late 1785, he was elevated to the governor’s executive advisory board, the Council of State, a position that carried both prestige and a salary. By the time he became a Council member, Braxton and Patrick Henry had made their political peace, and they worked together well during Henry’s term as governor of the state.

Braxton did not attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia or his state’s ratifying convention, but he did support the adoption of the Constitution.