Summary

Caesar Rodney road overnight on his horse from Delaware to vote for independence in Philadelphia. During the war, Rodney served as Delaware’s governor.

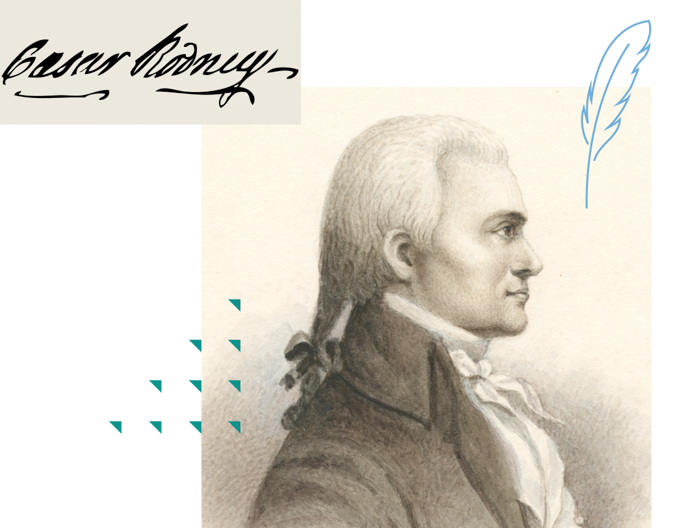

Caesar Rodney | Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:26

Biography

Caesar Rodney was born on his family’s plantation, “Byfield,” the eldest son of Caesar and Elizabeth Crawford Rodney. The Rodneys were members of the local gentry, whose 849-acre farm was worked by enslaved labor. His parents provided Caesar with early education at The Latin School, run by the College of Philadelphia [now the University of Pennsylvania], but his father’s death in 1746, when his namesake was 17, ended his formal studies. In 1763, his mother died and the 35-year-old Rodney inherited Byfield.

Even before he became the owner of Byfield, Caesar Rodney had taken his first steps into public service. In 1755, he was elected sheriff of Kent County, tasked with supervising elections and choosing the grand jurors who set the county’s tax rates. This gave him considerable influence in his community and, not surprisingly, he garnered new political positions when his term as sheriff ended. During the French and Indian War, he held a captaincy in the militia, and despite his lack of legal training, he was appointed in 1769 as a judge of the Supreme Court of the Lower Counties.

In the political contest between Delaware’s Court and Country Parties, Rodney’s county of Kent largely supported the majority Court Party that favored reconciliation with Britain despite the imposition of new taxes by Parliament. But Rodney sided with the Country Party’s strong opposition to Britain and supported its advocacy of independence. He aligned himself with the Country Party’s leader Thomas McKean and together these two men attended the Stamp Act Congress in 1765. Rodney was a member of the Delaware Assembly and, on several occasions, served as its speaker. The gavel was in his hands on June 15, 1776, when the Country Party persuaded the Assembly to sever all ties with Parliament and King George III.

Rodney and McKean, along with their political enemy, George Read, were chosen as delegates to the Continental Congress from 1774 through 1776. When the debate over independence began, Rodney was not present; he was in Dover, dealing with his duties as a Brigadier General in Delaware’s militia. This meant Read and McKean were representing their state when Lee’s resolution was on the table, and the two men were deadlocked on the vote. McKean sent word to Rodney that his vote on independence was urgently needed, and, late in the evening on July 1st, Rodney set out for Philadelphia. He gave this account of his midnight ride to his brother Thomas:” I arrived in Congress (tho detained by thunder and rain) time enough to give my voice in the matter of independence….We have now got through the whole of the declaration and ordered it to be printed so that you will soon have the pleasure of seeing it.”

John Adams, who could be counted on for commentary on most of the political figures of his day, described Caesar Rodney as “the oddest looking man in the world; he is tall, thin and slender as a reed, pale; his face is not bigger than a large apple, yet there is sense and fire, spirit, wit and humor in this countenance.”

Adams might not have known that Rodney suffered from severe asthma or that his odd looks were the result of an ongoing battle with facial cancer. In 1768, a doctor had operated on Rodney’s nose and left him disfigured. As he reported to his brother Thomas, the procedure had “left a hole, I believe, quite to the bone, and extends for length from the corner of my eye above half way down my nose.” This explained why, it is said, Rodney rarely appeared in public without a scarf on his face.

The cancer may have contributed to Rodney’s deepest heartbreak: his failure to win the affection of Mary Vining. Rejected by his “Molly,” Rodney remained a bachelor all his life. But if his personal life was unsatisfying, his political career flourished. During the war, he served as Delaware’s governor, as well as a major general in the state’s militia. In these capacities, he protected Delaware from the British army and controlled Loyalist activity. In 1777, Rodney was returned to the Congress, and then, in 1778, he was elected President of Delaware. In 1781, soon after Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, he resigned his office because of ill health.

When Delaware called on Caesar Rodney again in 1782 to serve in its General Assembly, he was too ill to comply. In 1783, the state’s Legislative Council showed their respect for Rodney by electing him their Speaker. But his cancer caused his health to rapidly decline, and he died before the Council’s session ended. He was 55 years old.