Summary

Benjamin Harrison was from a wealthy Virginia plantation family. He chaired the debate over the Lee Resolution and the adoption of the Declaration of Independence in July 1776.

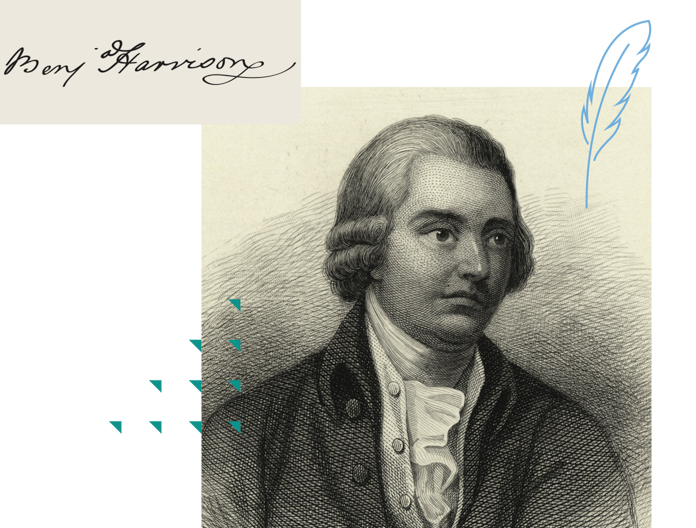

Benjamin Harrison | The Signer of the Declaration of Independence

2:41

Biography

Benjamin Harrison was born at the family homestead, Berkeley Plantation. As the fifth son who carried that name, he was often designated Benjamin V. He came into a large inheritance when his father was struck by lightning while closing a window during a storm. Both he and the young daughter he was holding in his arms died in this freak accident.

Thus, at the age of 19, Benjamin V became a very wealthy man, as he received the bulk of his father’s vast estate, including several plantations and thousands of acres of land. He also acquired numerous enslaved people. Tradition held that, as he was the eldest son, he ought to have inherited the entire estate, but Benjamin IV departed from that tradition, leaving six plantations and some enslaved people who worked their fields to the remainder of his children.

As befit a man of great wealth, Benjamin V served for three decades in the Virginia legislature known as the House of Burgesses. He was one of that colony’s earliest opponents of the new British policies that followed its costly 1763 victory in the French and Indian War. Harrison was particularly incensed by the Townshend Acts of 1767 that taxed a number of British items imported into the colonies, including tea.

In 1770, he signed the Virginia Association, which called for a boycott of British goods until the Tea Act tax was repealed. Early in 1772, he joined Thomas Jefferson and six other Virginia Burgesses in preparing an address to the King calling for an end to the importation of enslaved people into Virginia. Their motive was less humanitarian than economic; as tobacco prices fell and many planters shifted to the production of wheat, they hoped to reduce their workforce by selling slaves to new plantations across the Appalachians or south to the Carolinas and Georgia. As long as the flow of new slaves continued, the sale price they could demand would remain low. This request was ignored, but Jefferson would later include this issue in his draft of the Declaration of Independence.

In 1774, Harrison joined with other Burgesses in issuing an invitation to other colonies to convene a Continental Congress. He was selected to serve as one of seven delegates to this congress in August of that year. Many of the political leaders in this First Continental Congress were strangers to one another. John Adams’s early impression of Harrison was not positive. In his diary, Adams wrote that this tall and heavily built Southerner was, like other Southern planters, just “another Sir John Falstaff,” obscene, profane, and impious. Yet, Adams did concede that Harrison’s sense of humor often “steadied rough sessions” during the congressional debates.

In the Second Continental Congress, Harrison played the important role of chairing the final debate over both the Lee Resolution and the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Pennsylvania delegate Benjamin Rush recalled how relieved he was when Harrison interrupted “the silence and gloom of the morning” as the delegates, one by one, signed a Declaration they knew might well be their death warrant.

In 1777, Harrison became a member of Congress’s Committee of Secret Correspondence. Its task was to establish secure communication with American agents in Britain. He was also named Chairman of the Board of War. His good humor failed him when he and George Washington argued over whether the Marquis de Lafayette should be paid, as Washington insisted, or should serve as an honorary officer without compensation, as Harrison demanded. He also favored an unpopular cause: the right of Quakers to refuse to bear arms. And, during the debate over membership in the legislature of the Articles of Confederation government, Harrison argued that Virginia deserved greater representation because it was larger and more populous than its neighbors.

Harrison retired from Congress in October of 1777, a victim of the war. His estates had been ravaged by armies and his fortune had been severely reduced. Worse was soon to come. In 1781, Benedict Arnold led a British force to Virginia that seized Harrison’s Berkeley Plantation and removed and burned all the family portraits hanging on its walls. Most of Harrison’s possessions were destroyed. Yet in that same year, Virginians honored him by making him governor of the state. He served in that role until November of 1784.

In 1785, Harrison returned to the legislature, and later, in 1788, was chosen as a delegate to the state’s ratifying convention. At this contentious convention, he joined Patrick Henry and other Anti-Federalists in opposing the Constitution on the grounds that it did not contain a Bill of Rights.

In his last years, Harrison was plagued by gout and continuing financial troubles. He died in April of 1791. The cause of his death is unknown, but it is suspected that his excessive weight played a role in his demise.