Revisiting and Restoring Madison’s American Congress

By Sarah Binder, professor of political science at The George Washington University

Looking westward to Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains from his Montpelier library, James Madison in 1787 drafted the Virginia Plan—the proposal he would bring to the summer’s Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. Long after ratification of the Constitution—and after the Du Pont family had suffocated Montpelier in pink stucco—preservationists returned to Montpelier to restore Madison’s home. Tough to say the same for the U.S. Congress, the institutional lynchpin of Madison’s constitutional plan. True, Congress has proved an enduring political institution as Madison surely intended. But Congress today often misses the Madisonian mark. The rise of nationalized and now ideologically polarized parties challenges Madison’s constitutional vision: Lawmakers today are more often partisans first, legislators second. In this paper, I explore Madison’s congressional vision, review key forces that have complicated Madison’s expectations, and consider whether and how Congress’s power might (ever) be restored.

Madison’s Congressional vision

Madison embedded Congress in a broader political system that dispersed constitutional powers to separate branches of government, but also forced the branches to share in the exercise of many of their powers. In that sense, it is difficult to isolate Madison’s expectations for Congress apart from his broader constitutional vision. Still, two elements of Article 1 are particularly important for distilling Madison’s plan for the new Congress. First, Madison believed (or hoped) that his constitutional system would channel lawmakers’ ambitions, creating incentives for legislators to remain responsive to the broad political interests that sent them to Congress in the first place. Second, Madison expected that Congress would dominate the political system: Article 1 amassed significant political authority in the legislature, empowering new national majorities to solve public problems. To be sure, these two dimensions of Madison’s Congress are neither easily nor readily separated. But as I explore below, together they form the backbone of Madison’s vision for the new Congress.

Channeling ambition

As political scientist Charles Stewart has observed, Article I—which established the blueprint for Congress—was fairly prescriptive, encompassing more than half of the constitutional text.[1] But as Stewart reminds us, Madison understood that the Constitutional text would not enforce itself. As Madison wrote in Federalist 48, “a mere demarcation on parchment of the constitutional limits of the several departments, is not a sufficient guard against those encroachments which lead to a tyrannical concentration of all the powers of government in the same hands.”[2] In short, assigning dozens of critical constitutional responsibilities and powers to Congress did not guarantee that lawmakers would faithfully deploy them.

Instead, Madison believed that creating competing power centers within the political system would compel politicians to compromise: They would otherwise be unable to secure favored policy outcomes as they required agreement of the other chamber and the president. In perhaps the most frequently quoted line from the Federalist Papers, Madison observed that “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected to the constitutional rights of the place.” By focusing on political ambition (reinforced by frequent popular elections for House members), Madison suggested that the Constitution would channel lawmakers’ natural political impulses—both against one another and collectively against the president.

Madison was significantly less clear about how politicians’ interests would be fused to their constitutional rights as members of Congress. Left unstated was the mechanism that would secure lawmakers’ loyalty to the Congress. Historian Jack Rakove points out this ambiguity, noting that even in Federalist 51 Madison says little about how such attachments would form. Madison, Rakove reminds us, does suggest that senators and the president may find common cause in the exercise of their shared powers over diplomacy and nominations to check an overly ambitious House.[3] In that sense, ambition might indeed counter-act ambition. Madison more generally seemed to believe that juxtaposing political ambitions within Congress and between the branches would encourage lawmakers to protect Congress’s constitutional responsibilities. Who else in a system that separated powers within and across the branches would have an incentive to protect or exploit pivotal congressional powers?

That said, such an interpretation of what Madison likely meant by connecting men’s interests to the constitutional rights of the place risks misunderstanding Madison’s intent. As constitutional scholar Larry Kramer thoughtfully explains, Madison surely did not expect lawmakers to prioritize their institution over their political interests: “Even without political parties, why would anyone expect legislators to object to Presidential action they agreed with and supported?”[4] Rather, Kramer advises, we should interpret Madison’s twin focus on ambition and institutions as a statement about how the design of the Constitution would facilitate sound lawmaking: “These differences in how officials were chosen and to whom they were accountable mattered, because they meant that members of the different governments and of different departments within these governments would have different political interests and agendas.”[5] The challenge to making the Constitution work—meaning that it would ensure and protect popular control in a representative government—would be to harness these competing political interests to the constitutional authorities divided between and across the branches.

Empowering national majorities

Counter-balancing political ambitions served another purpose as well. Madison believed that counter-poising politicians’ ambitions would empower the new national government, but also limit how powerful government could become. A focus on fostering energy and action within the legislative branch contrasts sharply with perhaps the most commonly believed wisdom about the Constitution: That Madison bequeathed us a political system designed not to work. According to this view, fear of a powerful executive led Madison and many of his colleagues at the Constitutional Convention to appreciate—even prefer—governmental stalemate. Indeed, at times scholars have argued that the framers purposefully designed the Constitution to guarantee gridlock and gave Congress a starring role in that assignment. Separating powers into disparate branches, dividing authority between national and state governments, and empowering each of these separate institutions to check the others—political observers often hold up these features of the Constitution as evidence of the framers’ preference for stalemate. Deadlock, in this view, is the natural if not intended consequence of Madison’s constitutional plan.

What’s more, proponents of this view often suggest that gridlock signals the health of the Madisonian system. “Gridlock,” said the late Bill Frenzel (a Republican member of the House of Representatives from Minnesota), “is the best thing since indoor plumbing.”[6] Why? Frenzel offered a constitutional defense: The tendency towards gridlock is “a natural gift the Framers of our Constitution gave us so that the country would not be subjected to policy swings resulting from the whimsy of the public.” To the extent that the Madisonian system thwarts well-intended efforts to generate legislative action, that was a feature—not a bug—of Madison’s design.

Political scientists offer constitutional diagnoses as well. Writing in the 1960s to urge revitalization of the Democratic party and its leadership, James MacGregor Burns argued that we “underestimate the extent to which our system was designed for deadlock and inaction.” Burns squarely blamed Madison, whom Burns accused of “believ[ing] in a government of sharply limited powers. His efforts at Philadelphia were intended more to thwart popular majorities in the states from passing laws for their own ends than to empower national majorities to pass laws for their ends.”[7] Emphasizing the ways in which power sharing across institutions thwarted legislative majorities, these scholars suggest that Madison today would in fact appreciate the rising incidence of deadlock in America’s Congress.

Political scientist Charles Jones offers a competing, important, and often overlooked interpretation of the Framers’ intent:

It is worth remembering that the Founders were seeking to devise a working government. They did, of course, have fears about tyranny and thereby sought protection through competing legitimacies. But the point was not solely to stop the bad from happening; it was to permit the good, or even the middling, to occur as well.[8]

This alternative view suggests that the Founders sought a strong national government that could govern. The result was an “intricate balance between limiting government and infusing it with energy.”[9] Rather than viewing policy deadlock as the goal of Madison’s constitutional vision, we might better think of frequent policy deadlock as an unintended consequence.

Overcoming government gridlock

So what did Madison expect from his constitutional design? The inadequacies of the Articles of Confederation and political instability in the states that occurred under a variety of constitutional forms were foremost in Madison’s and the framers’ minds.[10] Madison and Alexander Hamilton believed that the impotence of the government under the Articles of Confederation Congress threatened the future of the new union. Indeed, they used the first half of the Federalist papers to explain the flaws of the existing government. These included a requirement for oversized majorities or unanimous support to enact the most important policies, contributing to the Confederation Congress’s failure to raise adequate revenue, command support from the states, protect commercial interests, support troops, and secure western expansion.[11]

Albeit with well-noted exception, delegates to the Constitutional Convention largely agreed with Madison and Hamilton's goal of a more centralized government.[12] They agreed in principle that the new union would require a much stronger national government, what Hamilton in Federalist 1 called “an enlightened zeal for the energy and efficiency of government.” Or as Madison summarized later in Federalist 37, both stability and energy were critical to good government.

Skeptics might point to the doctrine at the heart of the Constitution, the separation of powers, as evidence that Madison and his colleagues sought to hamstring the new government. To be sure, scholars typically portray the division of power between the legislative, executive, and judicial branches as a mechanism chosen by the framers to check or limit federal power. The separation of powers in this view restrains policy makers, thus encouraging stalemate instead of policy change. “It has not been an easy constitution with which to make policy quickly and to govern efficiently,” scholar Clinton Rossiter observed in the 1960s, “which is exactly the kind of constitution the framers intended it to be. The gaps that separate the executive from the legislature . . . have often been as discouraging to men of good will as to men of corrupt intent.”[13]

Consider a competing interpretation of the separation of powers. As Gordon Wood observed in studying the origins of the Constitution, the separation of powers had a unique meaning for the new nation: “When Americans in 1776 spoke of keeping the several parts of the government separate and distinct, they were primarily thinking of insulating the judiciary and particularly the legislature from executive manipulation.”[14] Rather than seeking to limit legislative capacity, the framers believed that the separation of powers could protect the autonomy of the judicial and legislative branches. The experience of royal governors intervening in the affairs of the colonial legislatures shaped such early American views about the separation of powers. Interestingly, after independence a decade later, the problem was reversed. Now, limiting legislative encroachment over executive responsibilities was central to the framers’ views about the separation of powers. Creating and protecting an executive separate from the legislature was critical to ensuring both legislative and administrative capacity in the new government.[15]

Note as well that the Framers did not detail the rules of the Congress in the Constitution. Instead, they delegated the rule making power to the House and Senate in Article 1, Section 5. Conspicuously absent from the Constitution—beyond the two-thirds vote required to ratify treaties, expel lawmakers, and impeach presidents and others—were the supermajority rules that often stalemated the Continental Congress. Nor did the members of the first House or Senate create rules that strongly limited the power of simple majorities to pass legislation.[16] Why did the Framers leave the choice of legislative rules to lawmakers? One view is that the framers had already designed the Constitution to make it prone to gridlock. If so, detailing procedural constraints on legislative majorities in the Constitution would have been unnecessary. The Constitution already featured staggered selection of senators and different electoral bases and terms of office for House and Senate members. What further constraints on lawmaking could be necessary?

But what if Madison and colleagues wanted to create a stronger and more efficient national legislature? If so, they might have avoided hamstringing the new Congress with the types of rules that had encumbered previous legislatures. Granted, we can never be sure why something did not happen. But we know for sure that both Hamilton and Madison opposed supermajority legislative requirements prescribed by the Articles of Confederation. Both men wrote explicitly about the dangers of limiting the powers of simple majorities. For example, consider Madison’s point in Federalist 58:

It has been said that more than a majority ought to have been required for a quorum, and in particular cases, if not in all, more than a majority for a decision. That some advantages might have resulted from such a precaution, cannot be denied . . . But these considerations are outweighed by the inconveniences in the opposite scale. In all cases where justice or the general good might require new laws to be passed, or active measures to be pursued, the fundamental principle of free government would be reversed. It would no longer be the majority that would rule; the power would be transferred to the minority.

Madison clearly felt compelled to defend the Framers’ decision not to impose supermajority requirements. The passage suggests that the Framers’ silence in the Constitution about internal legislative procedures cannot simply be interpreted as a sign that the Framers believed procedural restraints unnecessary.

In Federalist 22, Hamilton also attacked the structure of the Continental Congress, criticizing its rules that required a two-thirds vote of the states to pass legislation regarding revenue, spending, or military matters:

The necessity of unanimity in public bodies, or of something approaching towards it, has been founded upon a supposition that it would contribute to security. But its real operation is to embarrass the administration, to destroy the energy of government, and to substitute the pleasure, caprice or artifices of an insignificant, turbulent or corrupt junto, to the regular deliberations and decisions of a respectable majority.

Madison and Hamilton, in short, rejected writing for the new Constitution those institutional rules that had fostered stalemate in the old Congress—suggesting that the Framers at least sought to avoid some of the procedural traps that so often led to deadlock under the Articles of Confederation.

Revisiting the political context in which the constitutional delegates worked suggests that we temper our conventional interpretation of Madison’s congressional vision. In well-known ways, draftsmen of the Constitution sought to check and thus restrain governmental power, seeking to prevent the new government from sliding into tyranny. At the same time, opposition from Anti-Federalists during the ratification campaign gave Madison and the Federalists incentives to emphasize how power would be restrained—not enhanced—under the new Constitution. Regardless of the ratification campaign, Madison’s views about early Americans’ experiments with national legislatures surely limited his interest in hamstringing Congress’s governing capacity. Madison favored refining public opinion through representatives in Congress, but surely also sought to create a Congress that could spearhead solutions to national crises and public problems.

Madison’s Congress today

What would Madison think of Congress today? In many ways, Madison’s congressional vision was a stunning success. Congress has played a preeminent role in driving and shaping historical change in the U.S., and it remains the world’s longest lasting, popularly elected legislature. And as congressional scholar David Mayhew suggests in new work, The Imprint of Congress, Congress has often played a central role in steering America’s emergence as a global economic and political powerhouse across thirteen “transnational impulses” that recur across history and the world. Granted, Congress’s role has changed over time—sometimes it leads, other times it constrains the president, and still other times it watches more like a mere bystander. Even if eclipsed by a more politically powerful president by the turn of the twentieth century, Congress was the preeminent branch for much of the nation’s first century under the Constitution.[17] Moreover, in today’s more polarized times, lawmakers do still spearhead significant policy change. In this view, Madison might be pleased with what he would see: His vision for Congress took root early and successfully.

That is the more positive view of how Madison would react to his handiwork. A rival view surely holds weight: Madison would be deeply depressed at what he would find on Capitol Hill. From this perspective, Congress never had a chance. The emergence of nationalized political parties by the early nineteenth century set in motion trends that undermined Madison’s vision for the Congress. The result today is a willfully weak Congress: steadily rising legislative stalemate, limited oversight of the executive, lack of fiscal discipline, and excessive delegation to the executive and ultimately the courts. In fewer words, Madison might view Congress today as the “broken branch.”[18]

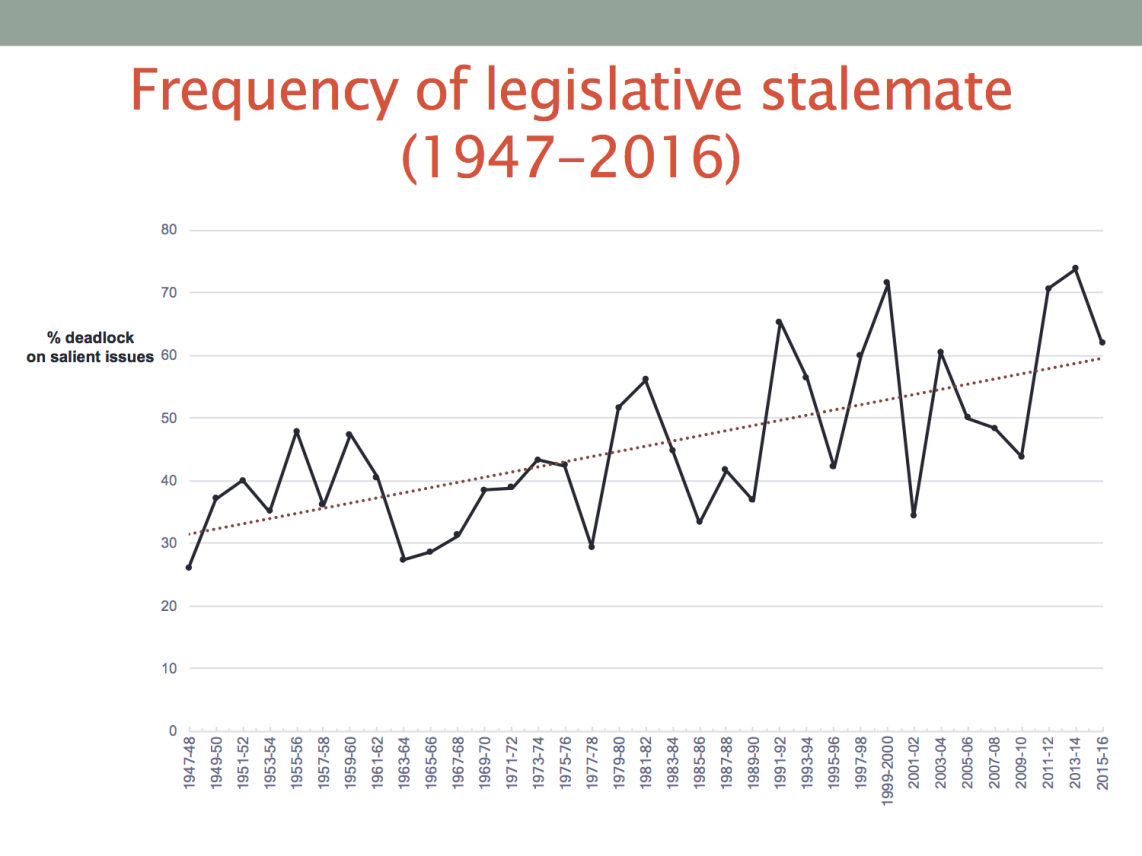

Regardless of where we believe Congress rests on the spectrum between optimistic and dire views of its performance, Congress has struggled for some time to incubate, deliberate, and compromise on legislative solutions to major public problems. Consider, for instance, the following figure that captures the degree of legislative stalemate over the long postwar period. Typically, we measure congressional performance by counting up the number of landmark laws that Congress and the president enact in any given Congress.[19] But if we want to know the degree to which Congress and the president stalemate on key issues, we also have to take account of the major issues that lawmakers fail to successfully address. In other words, rather than judge Congress only by what it does, consider as well what it could have done. To be sure, legislative inaction can reflect real, irreconcilable differences within Congress or across the branches. Moreover, if the parties disagree about whether an issue is actually a problem, it is no wonder they disagree on solutions. Still, neither party seems terribly pleased by inaction: Republicans who want to pare back regulations or Democrats desiring to stem global warming need a functional Congress to advance their agendas.

With that context, the measure below shows the degree of legislative deadlock in each Congress since the mid 1940s: What proportion of big ticket issues on the national agenda did Congress and the president fail to address?[20]

Three trends stand out. First, more of Congress’s agenda ends in stalemate today than it did decades ago. The steady upward climb in the percentage of issues in deadlock confirms perceptions that Congress struggles more to legislate today than it did in the past. Second, in its two highest periods of deadlock (after the first two years of the Clinton and Obama presidencies), Congress faltered on nearly three-quarters of its agenda. Most recently, stalemated issues include reforming immigration law, lowering the cost of health care and prescription drugs, stemming global warming, trimming future entitlement spending, investing in the nation’s infrastructure and so forth. Third, although the long-term trend suggests ever rising deadlock, some important variation stands out in Congress’s postwar record. Mostly significantly, until recently, unified party control had packed a small punch: Congress has historically been more productive in periods of unified than divided party control. But as ideological disagreements and sheer partisan team play have risen during the past decade, single party control no longer seems a silver bullet for fostering major policy change.

Why do these empirical patterns matter? As Jack Rakove reminds us, Madison believed that legislatures’ primary purpose was to wield legal authority, not merely to check an overbearing executive.[21] Madison and the Framers endowed the Congress with significant legislative tools and powers. Moreover, Madison expected the Congress to serve as the fulcrum of power within the broader political system. But Congress’s difficulty resolving major problems—coupled with decades of delegating authority over trade, foreign affairs, national defense and other issues to the executive—suggests that Congress struggles to perform that role. Add in the meager record of congressional oversight of the president in periods of unified party control, and it seems reasonable to conclude that Madison’s Article I vision and expectations have fared poorly over the longer term.

What went wrong

Mono-causal theories in American politics are rare. Certainly multiple forces have contributed to Congress’s contemporary governing difficulty. Nevertheless, one key historical development in the U.S. stands out: The evolution of political parties—first inside the legislature, later amidst an expanding electorate—undermined Madison’s legislative vision in key ways. First, the emergence of national parties challenged Madison’s scheme of counter-poising politicians’ ambitions. Second, over a longer period of time, presidents became the natural leaders of these new parties, which encouraged lawmakers to cede significant statutory and other powers to the presidency. Third, heightened partisanship at the end of the nineteenth century and again at the end of the twentieth—intensified divisions between the parties and complicated the formation of large bipartisan majorities necessary to get much done in Washington. Collectively, these three trends undermined Madison’s original congressional vision and have contributed to persistent and debilitating bouts of deadlock in the American Congress.

Framers’ hostility to political parties is well known. As Madison’s studies had convinced him, the key problem undermining most democracies historically had been the emergence of a tyrannous majority. Madison explained in Federalist 10 that the design of the new Constitution would guard against the emergence of such majorities. His plan took advantage of the great diversity of opinions and interests—economic, social, and political—inherent in an “extended republic” like the new United States: “Extend the sphere and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests.[22] As Larry Kramer reminds us, Madison was not opposed to popular majorities.[23] But he believed that large districts and an extended republic would ensure that factious majorities could not rule: The only persons who could in theory get elected in large House districts should have been those with the greatest public appeal. Madison counted on members of the House and Senate coming to Congress dedicated to pursuing the interests of their constituencies, rather than the interests of a party.

As became clear within the first few Congresses, Madison miscalculated how integral organized factions would become to lawmakers in both chambers. Granted, the early parties that formed in Congress were hardly parties by today’s standards: Given how small and selective state electorates were at the time, these proto-parties organized politics within the Congress but not outside.[24] Only as states began to extend suffrage beyond property-holding elites did politicians begin to realize how robust parties could be instrumental for mobilizing voters behind prominent or promising presidential candidates. As political scientist John Aldrich has argued, full-fledged political parties solved key problems of politics: They made winning, durable coalitions possible inside Congress, cued voters about competing party policy promises, and turned out voters at election time.

The development of national parties was problematic for Madison’s vision for Congress. As Charles Stewart argues, lawmakers began to come to Washington “predisposed to cooperate with their co-partisans and resist the opposition.”[25] What’s more, lawmakers gradually came to lean on presidents—especially from their own party—for policy leadership in Washington. Rather than pursuing the interest that elected them in the first place, legislators’ loyalties were increasingly to their parties. By failing to anticipate the twin rise of nationalized parties and expanded electorates, Madison underestimated how difficult it would be to keep power dispersed within the new political system. Parties provided bridges between the separate branches and created distinct walkways for each of what would much later become the Democratic and Republican parties.

The emergence of nationalized parties—with all but popularly elected presidents at the helm—also posed a challenge to Madison’s vision of Congress as the linchpin of the political system. As Stewart points out, the only real formal tool presidents held under the Constitution was the veto power. For any other resources—“money, troops, patronage”-- presidents had to turn to Congress.[26] But presidential subordination to Congress weakened with the rise of nationalized parties with presidents at the helm. The power to command public attention—fleetingly in the nineteenth century and more permanently in the twentieth—created political leverage that Madison likely did not anticipate. Coupled with the rise of nationalized, electorally-based parties over the course of the nineteenth century, presidents—not lawmakers—emerged in the early 1900s as the preeminent leaders of their parties and a national government.

Congress was no innocent bystander in the development of presidential power. In fact, lawmakers aided and abetted it, and sometimes instigated it. Bouts of delegation and institutional building within the executive branch and the White House occurred over matters of war and budgets, most visibly during the Great Depression in the 1930s and in the ensuing run up and aftermath of World War II. Indeed, Congress created the “national security state”—including a permanent standing army and an enormous national intelligence apparatus. These delegations of power were in effect zero sum moves: Lawmakers were happy to cede power to popular presidents and ride their coattails to re-election. Conceptually, Congress delegated power with the threat that they could recoup it. But apart from a short-lived period of congressional resurgence in the 1970s, over the long-term Congress has empowered presidents and exercised uneven oversight over how presidents deploy those powers.[27]

Today’s presidents—electorally and institutionally empowered—drive nationalized politics and policymaking in a deeply partisan environment. Today’s political parties are more polarized ideologically and more electorally competitive than they have been since the end of the nineteenth century.[28] What’s more, politics is increasingly nationalized, putting to pasture the maxim that “all politics is local.”[29] Scholars debate what precisely our measures of partisan polarization capture. One camp emphasizes the emergence of ideologically sorted parties into liberal and conservative camps in the aftermath of the civil rights revolution in the mid 1960s that allowed a robust Republican party to take root in the previously one-party, Democratic South. Others argue that polarization extends beyond questions of ideology to capture the growth of rival partisan teams: Your team is for it, so mine is against it.[30] Both notions capture polarization at the elite level and belatedly and increasingly across the electorate. And both help to explain why Madison’s vision for Congress as the driver of policy and defender of its interests has not fared well, particularly in modern times.

Perhaps most importantly, the roots of Congress’s decline predate the Donald Trump presidency. To be sure, America’s constitutional order might seem particularly fragile under Trump’s visceral style of politics, his often dismissive attitudes about the rule of law, his demonization of opponents, and the Republican Congress’s unwillingness to investigate controversial Trump administration policies and personnel.[31] But nationalized political parties took root in American politics nearly two centuries ago. Congress long ago endowed the president with enormous institutional resources and power. The public long ago turned to presidents as the preeminent leaders of the American political system. And the current incarnation of partisan polarization has been on the rise at least since the early 1990s. In short, lawmakers’ ambitions seem hitched to their presidents’ goals and only sometimes attend to the “Constitutional rights of the place.”

Hope for Madison’s Congress?

Reformers are unlikely to resurrect Madison’s vision for Congress. After more than two centuries of American political development that have made presidents the most pivotal actors in a highly partisan polity, the Madisonian ship has sailed. As political scientist E.E. Schattschneider famously wrote more than a half-century ago, “the political parties created democracy and . . . modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of parties.”[32] Only parties, Schattschneider argued, could provide the sort of majoritarian organization necessary to fairly contest elections in a democratic society. Absent parties, factions would mobilize on behalf of narrowly drawn, biased sets of interests. Madison certainly saw the benefit to such a system of countervailing factions. But with the benefit of hindsight, Madison’s constitutional scheme to guard against tyrannous majority factions seems anachronistic.

True, the intensity of partisanship could dissipate over coming generations. Lowering the partisan temperature could make it easier for future parties to resolve major policy problems by creating broader constituencies for compromise within each party. But it seems difficult to imagine a wholesale reversion to congressional preeminence envisioned by Madison. Nor are states ever likely to provide the sort of counterweight to national ambition and power prized by Thomas Jefferson and the Anti-Federalists at the Founding. Most accounts of subnational politics today emphasize how nationalized parties now dominate politics that play out at the state level.[33]

That does not mean that reformers should abandon efforts to make Congress work better. The challenge is figuring out what sorts of reforms—changes to the rules of the game, bolstering legislative capacity, or generating greater political will to solve public problems—are likely to be the most fruitful.[34] Of these three targets, improving legislative capacity is probably the easiest. True, lawmakers do sometimes resist informational resources on the grounds that they amplify the agendas of the opposition party. Republican cuts to staff in committees and the Congress’s research arms starting in the 1990s seemed in part designed to undermine the resources that Democrats had relied on during the long tenure in power. But in principle, augmenting legislative resources—given declines in policy experts within the standing congressional committees and legislative support agencies such as the Congressional Budget Office—should not be too politically difficult.

The other targets are much harder. Consider first the task of revamping institutional rules or practices of Congress. Politicians typically choose rules that they believe will help them to achieve their most preferred outcomes. And rules often develop unanticipated consequences that run counter to the intentions of reformers. That means that the best laid plans of reformers will get little traction if they fail to serve the intertwined policy and political goals of lawmakers. For example, many experts argue that the congressional budgeting process is broken. Designed for the politics of the 1970s, it now often fails to achieve its goals of rationalizing the budgeting process and bolstering Congress’s role in meeting the country’s fiscal needs.[35] And we can gin up reasonable, tractable reforms of budgeting rules and practices. But for reform to succeed, lawmakers need to be convinced that the changes will help them to secure their own goals. Reform for reform’s sake is rarely a clarion call in Congress. That said, significant turnover in Congress in recent years could generate pressure on leaders for reform, perhaps pushing the parties to adopt new ways of budgeting.

Similarly, absent sufficient electoral motivation for lawmakers to overcome legislative stalemate, deadlock is likely to be a recurring and feature of congressional politics. Only when lawmakers personally feel that a deadlocked Congress costs them electorally are they likely to advocate reforms to make the institution function better. Until then, lawmakers will surely continue to “run for Congress by running against it”—Richard Fenno’s electoral trope that captures lawmakers’ proclivity for deflecting blame for a dysfunctional Congress.[36]

Rather than propose reforms that aim to reduce polarization, we might instead try to adapt current modes of legislating to a highly polarized environment. This means finding ways to facilitate compromise when there is no ideological sweet spot on which partisans can agree. As Frances Lee and I detail in earlier work, rather than construing legislative deal making as “zero-sum,” a more productive approach conceptualizes deal making as positive sum.[37] We can think of this approach as enlarging, rather than dividing, a fixed size policy pie. The goal is to move Congress towards “win-win” deal making: both parties secure their most preferred outcomes rather than giving the dominant party what it wants at the other party’s loss.

Consider the following example from a 2013 bipartisan Senate agreement to reform the nation’s immigration laws.[38] Democrats secured a path to citizenship for undocumented persons, Republicans obtained vastly increased spending on border security, and business and agricultural lobbies agreed to visa and guest worker programs. Granted, the House failed to act. But the process by which senators reached a bipartisan deal—including working to understand the top priorities of other party, closing the doors temporarily at the start of the process to facilitate a deal—suggests a template for reaching agreement on at least some of today’s contentious issues. The model has also worked reasonably well since 2013 when the two parties have run up against stringent spending caps enforced by the Budget Control Act: On three occasions, party and budget committee leaders orchestrated spending deals to avoid automatic, across-the-board cuts.

Of course, some issues will be impervious to change in the short term. First of all, the parties do not always agree whether or not an issue constitutes a problem that calls for a solution. Democratic and Republican disagreements about global warming are a case in point. So long as Republicans dispute whether global warming is caused by human activity, there is little chance that Republicans will enter policy negotiations over solutions. Second, for bargaining to take place on any issue, both parties have to believe that they will pay an electoral cost for refusing to negotiate. House Republican opponents of immigration reform pushed their leaders in 2013, for example, to ignore the Senate’s immigration deal: Republican rank and file—and thus their leaders—saw little electoral reward for joining Democrats at the bargaining table for a set of reforms opposed by their largely white, conservative constituent base.

In such a polarized environment, congressional politics often plays out in messaging battles between the parties rather than in any sort of deliberative process on Capitol Hill. Those battles make it extraordinarily difficult to get the parties to negotiate over most of the big ticket items on Congress’s agenda. To be sure, all the attention to deadlock on the most controversial issues risks losing sight of more incremental, bipartisan policy change that often takes place out of the media’s spotlight. But on the major problems facing the country today, blaming the other party for inaction often plays better with the party base than casting controversial votes that accommodate the other party’s interests.

That leaves us with a national legislature plagued by low legislative capacity and halting political will to tackle tough problems. Half measures, second bests, and just-in-time legislating are the new norm: Electoral, partisan, and institutional barriers often limit Congress’s capacity for more than lowest-common-denominator deals. Even if lawmakers ultimately find a way to get their institution back on track, Congress’s difficulties have been costly—both to the fiscal health of the country and to citizens’ trust in government. The economy is regaining its footing. Regenerating public support for a Congress that barely reflects Madison’s ideal will likely prove much harder.

Notes

[1] Charles Stewart III, “Congress and the Constitutional System,” in The Legislative Branch, Paul J. Quirk and Sarah A. Binder, eds. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 4-5.

[2] “Federalist 48,” Avalon Project. The Federalist Papers, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed48.asp [Oct. 4, 2018].

[3] See Jack Rakove, “James Madison’s Political Thought: The Ideas of An Acting Politician,” in A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe, First Edition, Stuart Leibiger, ed., (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2013).

[4] Larry D. Kramer, “‘The Interest of the Man’: James Madison, Popular Constitutionalism, and the Theory of Deliberative Democracy,” 41 Val. U. L. Rev. 697 (2007), 726.

[5] Kramer, “The Interest of the Man,” 735.

[6] Bill Frenzel, “The System is Self-Correcting,” in Back to Gridlock: Governance in the Clinton Years, James L. Sundquist, ed. (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1995), 105.

[7]James MacGregor Burns, The Deadlock of Democracy (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1963), 22.

[8] Charles O. Jones, “A Way of Life and Law: Presidential Address to the American Political Science Association,” American Political Science Review 89(1) 1995, 3.

[9] James A. Morone, The Democratic Wish: Popular Participation and the Limits of American Government, Revised edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 336.

[10] Numerous scholars have tackled the political and intellectual currents leading to the Constitutional Convention. For comprehensive treatments see, among others, Terence Ball and J.G.A. Pocock, Conceptual Change and the Constitution (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1988); Lance Banning, The Sacred Fire of Liberty (Cornell University Press, 1995); Forrest McDonald, Novus Ordo Seclorum (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1985); Jack A. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (New York: Knopf, 1996), and Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1969). On the institutional dilemmas engendered by the structure of the Confederation Congress, see Calvin C. Jillson and Rick K. Wilson, Congressional Dynamics: Structure, Coordination, and Choice in the First American Congress, 1774-1789 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994).

[11] See Rakove, Original Meanings, chapters 1, 2.

[12] John R. Roche, “The Founding Fathers: A Reform Caucus in Action,” American Political Science Review, vol. 55, no. 4 (December, 1961); Isaac Kramnick, Introduction to The Federalist Papers, By Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison (New York: Penguin Books, 1987); and Frances E. Lee and Bruce Oppenheimer, Sizing Up the Senate (University of Chicago Press, 1999), chapter 2.

[13] Clinton Rossiter, Parties and Politics in America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1960), as cited in James L. Sundquist, “Needed: A Political Theory for the New Era of Coalition Government in the United States,” Political Science Quarterly 103(4) (1988-1989), 620.

[14] Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 57.

[15] Similar interpretations of the separation of powers have been suggested by Louis Fisher, President and Congress; Power and Policy (New York: Free Press, 1972), Chap. 1 and Appendix; Hugh Heclo, “What Has Happened to the Separation of Powers?,” in Bradford O. Wilson and Peter W. Schramm, eds. Separation of Powers and Good Government (Boston: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1994); Michael Malbin, "Was Divided Government Really Such a Big Problem?" in Wilson and Schramm, eds. Separation of Powers and Good Government; and Garry Wills, A Necessary Evil (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999).

[16] Not until 1806 was the “previous question motion” eliminated in the Senate, a rule that could have been used by a simple majority to cut off debate. That rule change made possible unlimited debate, or the filibuster as it became to be known later in the nineteenth century. On the origins of the filibuster, see Sarah A. Binder and Steven S. Smith, Politics or Principle? Filibustering in the United States Senate (Brookings Institution Press, 1997).

[17] On the change from congressional to presidential dominance, see Joseph Cooper, “From Congressional to Presidential Preeminence: Power and Politics in Late Nineteenth Century America and Today,” in Congress Reconsidered, 8th ed., Lawrence Dodd and Bruce I. Oppenheimer, Eds. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2005).

[18] Among the many studies of these trends, see Sarah A. Binder, Stalemate: Causes and Consequences of Legislative Gridlock (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2003), Douglas L. Kriner and Eric Schickler, Investigating the President: Congressional Check on Presidential Power (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017), and Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein, The Broken Branch: How Congress is Failing America and How to Get it Back on Track (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

[19] The exemplar study in this vein is David Mayhew, Divided We Govern (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991).

[20] Details on measurement appear in Binder, Stalemate, chapter 3. For a more current treatment, see Sarah Binder, "The Dysfunctional Congress," Annual Review of Political Science 18 (May): 85-101.

[21] See Jack Rakove, “James Madison’s Political Thought: The Ideas of An Acting Politician,” in A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe, First Edition, Stuart Leibiger, ed., (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2013).

[22] “Federalist 10,” Avalon Project, The Federalist Papers, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed10.asp [Oct. 6, 2018].

[23] Kramer, op cit.

[24] On the institutional development of parties in and outside of Congress, see John H. Aldrich, Why Parties? A Second Look (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

[25] Stewart, “Congress and the Constitutional System,” 3.

[26] Stewart, “Congress and the Constitutional System,” 24.

[27] On the politics of Congress’s 1970s resurgence, see James Sundquist, The Decline and Resurgence of Congress (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1981).

[28] On the rise of polarized parties, see Nolan McCarty, Keith Poole, and Howard Rosenthal, Polarized America (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006). On the political impact of electoral competitiveness, see Frances E. Lee, Insecure Majorities (Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2016).

[29] On the nationalization of American politics, see Daniel Hopkins, The Increasingly United States: How and Why American Behavior Nationalized (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

[30] Lee, Insecure Majorities.

[31] The track record of the Republican Congress’s willingness to challenge Trump’s prescriptions and policies deserves a full-fledged study of its own. Certainly some issues did provoke varying degrees of Congressional pushback. A bipartisan Congress imposed sanctions on Russia for meddling in the 2016 election. Republican senators pressed the administration to limit the imposition of tariffs that hurt the agricultural economy. As of this writing, Congress has refused to fund the administration’s proposed wall along the South western border. And GOP and Democratic leaders threatened to curtail the administration’s “zero tolerance” strategy of separating immigrant families at the border. Still, Republicans undertook little if any oversight of these and other equally controversial matters during Trump’s first two years in office.

[32] E.E. Schattschneider, Party Government (Chicago: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1942), 1.

[33] On the nationalization of state politics, see Hopkins, The Increasingly United States, and Steven Rogers, “National Forces in State Legislative Elections,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667 (1) 207–225.

[34] This approach leaves to election law experts potential changes to electoral and campaign finance laws outside of Congress.

[35] Molly E. Reynolds, “This is why the Congressional budget process is broken,” The Washington Post, October 27, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/10/27/this-is-why-the-congressional-budget-process-is-broken/?utm_term=.379e3e639edf. Congress created a bipartisan panel to propose budget reforms, with recommendations due by November 28, 2018.

[36] See Richard F. Fenno, Jr., Homestyle: House Members in Their Districts. (Longman, 1978).

[37]Sarah A. Binder and Frances E. Lee, “Making Deals in Congress,” in Solutions to Political Polarization in America, Nathaniel Persily, ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

[38] See also Ryan Lizza, “Getting to Maybe,” The New Yorker, June 24, 2003. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/06/24/getting-to-maybe.