A big Supreme Court case to be heard this spring is focused on a powerful part of the Constitution, which could be changed or better defined by a spirited family of California raisin growers.

The Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause allows a government agency to take the personal property of citizens if it can prove the taking benefits the public and just compensation is paid to a property owner.

The Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause allows a government agency to take the personal property of citizens if it can prove the taking benefits the public and just compensation is paid to a property owner.

Over the years, the Takings Clause has led to some landmark Supreme Court decisions, such as Penn Central v. New York City (1978), which involved compensation for a government taking, and Kelo v. City of New London (2005), which was about the use of eminent domain to benefit a private party, and not the government.

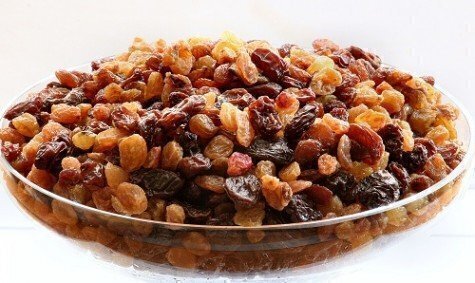

A new candidate for that canon of Fifth Amendment constitutional cases is Horne v. Department of Agriculture, which involves raisins and the power of the federal government to confiscate part of a grower’s crop.

Arguments will be heard in April 2015 by the Justices for a second time in the Horne case; the Supreme Court first ruled in 2013 that the raisin folks had a right for their arguments to be heard in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Having lost in the appeals court after the 2013 Supreme Court decisions, the Hornes asked for a second date with the Supreme Court, which agreed in January to hear about a complicated three-part question:

First, does the federal government need to pay someone for taking their personal property (such as raisins) or just real estate? Second, can the government take raisins, or any other property, and just give part of the sales proceeds to the former owner to justify the taking? And third, can the government require as a condition of doing business the surrender of part of a raisin crop?

At the heart of the argument is something called a Raisin Marketing Order, which dates back to the Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act of 1937. The order was first used in 1949 and it requires growers to turn over a percentage of handled raisins to the federal government. The government removes surplus raisins from the market to regulate raisin prices, and often resells part of its confiscated raisin horde to the market, giving some proceeds back to the growers.

Back in 2013, Justices Antonin Scalia and Elena Kagan raised questions about the raisin-taking order during oral arguments.

"Your raisins or your life, right? . . . You don't have to pay the penalty if you give us the raisins,” Scalia asked about fines imposed on raisin farmers who balked at the order.

Kagan said in 2013 that the case needed to go back to the Appeals Court so it could “try to figure out whether this marketing order is a taking or it’s just the world’s most outdated law.”

In April, the Justices will get another chance to pepper the attorneys representing the government and the Hornes about the law.

Writing the brief that the Court accepted for Horne was Michael McConnell, a noted constitutional scholar and former federal judge.

“The government has shifted arguments three times, from jurisdiction to standing and now to title, all in an attempt to evade the simple conclusion that when the government takes property, sells it, and uses the proceeds for its own purposes, it is required under the Fifth Amendment to pay just compensation,” McConnell said.

The federal government’s advocate, Solicitor General Donald Verrilli, argued the Ninth Circuit correctly decided the case based on several factors: that the 65-year-old agreement has generally benefited raisin farmers; the farmers get proceeds from the resale of the confiscated raisins; and that farmers already have a way to get compensation, through the Tucker Act, to seek payment in the Federal Claims Court.

One very interested side party in the case is the state of Texas, which filed its own friend of the court brief supporting Horne. In October, then state attorney general Greg Abbott asked the Supreme Court to clarify the true nature of marketing orders.

“The decision … has introduced uncertainty to an area of law that extends well beyond agricultural interests. It sows confusion for both property owners and condemnors,” said Abbott, arguing that the Nine Circuit Appeals Court’s decision had a broad impact on Fifth Amendment takings cases.

One point certainly to generate a debate among the Justices is the difference between personal property and real estate under the Fifth Amendment, and how the Horne case defines the difference.

In its brief, the government argued that its power to regulate raisins without a Fifth Amendment taking was “at its apex” in the Horne case, an argument that should get a lot of discussion in court.