With House Republicans winning enough votes to pass a bill repealing Obamacare, the long-held tradition of the Senate filibuster for legislative acts may be fighting for its life.

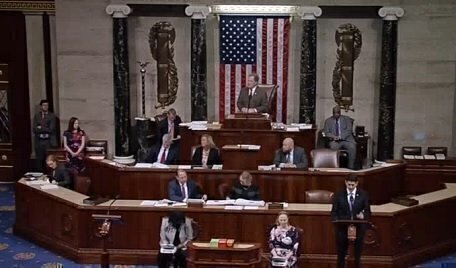

The House passed legislation on Thursday that would effectively gut the Affordable Care Act. But as with any proposed law, the Senate must approve the same bill, modify it, or reject it, before its goes to the President for his approval.

The House passed legislation on Thursday that would effectively gut the Affordable Care Act. But as with any proposed law, the Senate must approve the same bill, modify it, or reject it, before its goes to the President for his approval.

In the House, a simple majority was needed for passage, but the Senate requires 60 votes out of 100 for a bill to make it to the floor for consideration. This tradition, which dates back to Aaron Burr’s time, ensures that a supermajority of Senators, usually from competing political parties agree on controversial or important legislation.

Therefore, House Republicans can pass an Obamacare repeal bill, but it becomes a moot point if the Senate doesn’t pass the same bill. That leaves the current Senate with few options.

One option is for eight Democrats to join the 52 Senate Republicans in agreeing on the same Obamacare repeal plan. That seems like a long shot at best. A second option is for the Senate to pass its own Obamacare repeal bill, forcing members to both chambers to agree to a reconciled or amended bill that would pass in the House and Senate at a future date. A third option is for Senate Republicans to vote against an Obamacare repeal, also another long shot.

The final option is for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to use a procedural move to kill the legislative filibuster, the last filibuster left standing in the Senate, so that the House version or a reconciled version of an Obamacare repeal bill can pass the Senate.

Ironically, the original Obamacare act didn’t face this problem, since the Democrats had a supermajority of the Senate when the act passed in 2010. But now, there is little Democrats can do, aside from offering public protests, to stop the filibuster’s demise on McConnell’s part.

And McConnell, as he did with the move to kill the Supreme Court filibuster, could use the same tactics deployed by Harry Reid in 2013 to kill the filibuster for executive appointments.

While it is too soon to speculate in detail about an Obamacare repeal bill in the Senate, President Donald Trump and other GOP leaders have endorsed the idea of killing the filibuster entirely, which would greatly simplify the process of passing the Obamacare repeal act.

Publicly, Senate Majority Leader McConnell has opposed any efforts to eliminate the legislative filibuster. When asked at a press conference this week about killing the filibuster, McConnell said, “that will not happen.”

"There is an overwhelming majority on a bipartisan basis not interested in changing the way the Senate operates on the legislative calendar,” McConnell explained.

One procedural way for the Republicans to get the Obamacare repeal bill around the filibuster is through a process called reconciliation. A bill that strictly deals with budgetary matters can be presented with a limited debate time in the Senate, eliminating the filibuster as an option. However, Senate Democrats are already pointing at details in the House bill, such as changing existing provisions about pre-existing coverage conditions, which would lead to a procedural battle over the reconciliation process.

The Democrats would cite the Byrd Rules, where “the Senate is prohibited from considering extraneous matter as part of a reconciliation bill or resolution or conference report,” as blocking the House Obamacare repeal bill from getting a vote without 60 Senators approving that move.

However, Republicans could also use a second parliamentary tactic to have the presiding officer of the Senate, Vice President Mike Pence, ask the Senate parliamentarian to rule on the Democrats’ complaints. In theory, Pence could decide not to ask for a ruling, if he felt that was appropriate, and let the House bill proceed to a vote under the filibuster-free reconciliation process. But that likely would require McConnell’s involvement in a process that would have the effect of getting around the filibuster, an act he has already opposed.

As of Thursday, a more likely option in the Senate would seem to be for the incoming House Obamacare bill to be modified to fit the reconciliation process. The reconciliation process can only be used once annually, and the Republicans are also pursuing tax reforms and other measures best suited to that process, too.

And one politically sensitive item that could survive the reconciliation process would be a decision to leave Obamcare coverage in the bill for members of Congress and their staff. Removing that language could run afoul of the Byrd Rules that govern the reconciliation process.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.