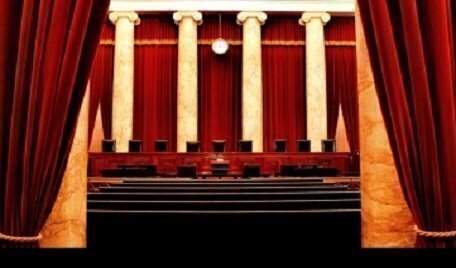

The U.S. Supreme Court may wrap up its term in the next two weeks and many in the nation are watching closely for potential blockbuster decisions on abortion, guns, religion, and climate change. But there is much more to learn from one of the most unusual and important Supreme Court terms in recent years.

First, don’t forget the “under the radar” cases.

First, don’t forget the “under the radar” cases.

During the course of a term, there are many more decisions that don’t grab front page headlines than do. These “under the radar” rulings often have major practical impacts on more people’s lives than those blockbuster decisions.

Less than two weeks ago, for example, the justices, interpreting the Federal Arbitration Act, unanimously ruled that Southwest Airlines cargo loaders and ramp supervisors were exempt from the arbitration law because they fell within an exception in the law. For Latrice Saxon, who had brought a class action lawsuit alleging failure to pay proper overtime wages, the decision meant that she could pursue her suit in federal court under the federal Fair Labor Standards Act instead going through arbitration with Southwest.

The decision potentially could affect hundreds or more workers if they have similar work situations. It also was a somewhat rare victory for workers in arbitration before the Supreme Court. The justices in general have been strongly pro-arbitration, believing it to be a more efficient, less expensive way of resolving disputes. However, there is a contrary view that believes arbitration is tilted in favor of employers.

In the next few weeks, the justices will decide the case of a Texas state trooper and army reservist who was called to active duty and deployed to Iraq in 2007. While in Iraq, he suffered lung damage from the toxic fumes from burn pits used by the military for waste disposal.

Honorably discharged, LeRoy Torres returned home unable to perform all of his duties as a state trooper and asked to be assigned a different position. The Texas Department of Public Safety rejected his request. Torres sued in state court under the federal Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act of 1994 (USERRA).

The public safety department argued that as a state agency, it had sovereign immunity from the lawsuit.

The USERRA was enacted under Congress’ war powers. The question for the justices in Torres case is whether states gave up their sovereign immunity in suits involving Congress’ war powers when they ratified the Constitution.

Torres has drawn supporting briefs from a number of military and veterans groups as well as war power legal scholars. On the other side, 15 states argue to retain state sovereign immunity. The USERRA, which guarantees an employee returning from military service or training the right to be reemployed at his or her former job, applies to virtually all employers including the federal government.

Second, what about Justice Amy Coney Barrett?

This term is the first full term for Barrett who took her seat on the high court in late October 2020 when the 2020 term was already underway. While she has been a reliable conservative vote, there is still much to learn about her.

End-of-term decisions are often in the year’s most contentious cases and result in divided votes. Those divided votes and the separate opinions in which the justices explain their votes can be the most revealing. We know that Barrett is a clear and direct writer, but how much of the “originalist” that she claims to be is she really?

Third, wither Chief Justice John Roberts Jr?

Before the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and confirmation of Barrett created a six-justice conservative majority, the chief justice was the median justice who could influence the outcome in close cases by moving left or right. He was never a true “swing” justice, but he sometimes was the moderating influence on the court.

After Barrett became the sixth conservative justice, Roberts’ vote was no longer needed to make five conservative votes for a majority. What role, if any, will he play in the term’s remaining, most closely watched cases?

Fourth, standing by or abandoning prior decisions?

Every Supreme Court nominee is asked about and speaks respectfully of the doctrine of stare decisis, which means standing by precedents. They dutifully recite the factors that the court considers when determining whether to overrule a prior decision.

The justices have been fighting over the proper application of stare decisis for some time. Their views range from Justice Elena Kagan’s staunch defense of stare decisis which, she says, demands a special justification for overruling a prior decision, to Justice Clarence Thomas’ position that “We use stare decisis as a mantra when we don't want to think.”

Expect to see this fight play out in the justices’ opinions on whether to overrule the landmark abortion rights precedents, Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey.

Finally, at the end of the term, what will you think of your Supreme Court?

The Supreme Court is, by many accounts, a wounded institution. Public approval of the court has dropped precipitously in recent national polls. The leaked draft opinion overturning Roe created turmoil inside and outside of the court. The justices have fought over their use of the so-called shadow docket to decide controversial cases without arguments and explanations. An eight-foot fence was erected around the court as an extra security measure. A man who wanted to kill Justice Brett Kavanaugh because he was upset about the leaked draft opinion and the pending gun rights case, was arrested near the justice’s home. And Justice Thomas’ wife is becoming part of the House committee investigation of the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

How the justices resolve the complex and polarizing issues remaining in the term may well answer that final question.

Marcia Coyle is a regular contributor to Constitution Daily and the Chief Washington Correspondent for The National Law Journal, covering the Supreme Court for more than 20 years.