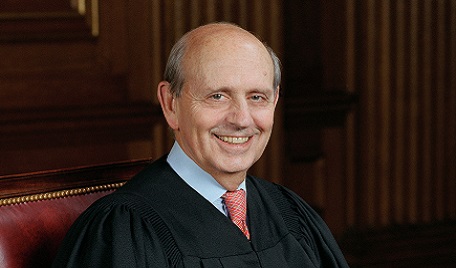

By the end of the current U.S. Supreme Court term or shortly afterward, a justice will retire, predict some court scholars and political experts. And that justice, they say, will be Justice Stephen Breyer. But when it comes to retirement decisions, justices don’t always follow conventional wisdom or expert predictions.

The focus on Justice Breyer is understandable. At age 82, he is the oldest of the three remaining Democratic-appointed justices. The others are Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

The focus on Justice Breyer is understandable. At age 82, he is the oldest of the three remaining Democratic-appointed justices. The others are Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

President Joseph Biden has said he will appoint the first Black woman to the high court, and civil rights groups and others are eager to see that promise fulfilled.

But perhaps the most important reason for the pressure now building for Breyer’s retirement within the next two years is the political calculus in the U.S. Senate. That body’s fragile 50-50 Democratic majority with Vice President Kamala Harris holding a tie-breaking vote could evaporate in the mid-term elections.

Given that political situation, many believe there is only a small window of opportunity for the new president to appoint and to get confirmed a justice of similar ideology who could serve for many years to come.

As for Justice Breyer, he has said in recent interviews that he will eventually retire but it’s hard to know exactly when. He also cautioned, “The more the political fray is hot and intense, the more we stay out of it.” But based on his demeanor on the bench and his public comments about the court, Justice Breyer still very much enjoys his work.

Legal scholars and empiricists over the years have devoted enormous effort to psyching out the factors that drive a justice’s decision to retire. One theory is “strategic retirement” which has documented that a justice is more likely to retire when the president is of the same political party as the president who appointed the justice.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, appointed by President Bill Clinton, resisted pressure to retire during President Barack Obama’s eight years in the White House when, if she had retired, Obama likely would have nominated someone of similar ideology.

The political departure hypothesis states that justices will wait to retire until they think they are likely to be replaced by a justice with a similar ideology. They may wait until they believe their political party has a strong influence on presidential nominations. But other studies have found little relationship between retirements and political timing.

Another study found that age, health, tenure, and retirement benefits affect a justice’s retirement decision much as those factors do other populations.

A 2019 study by Christine Chabot of Loyola University of Chicago law school found that even justices who retired under a president of the same political party of their appointing president did not always see a like-minded successor. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor retired during the George W. Bush administration in order to care for her husband who suffered from Alzheimer's disease. Her successor was Justice Samuel Alito Jr., who was considerably more conservative than O’Connor. She later expressed unhappiness with some of Alito’s rulings.

Chabot’s study concluded that ultimately “poor health and a strong personal desire to remain on the court often dominated political concerns in the timing of recent retirements. As a result, political timing has played only a limited role in justices’ retirement decisions in the modern era.”

That brings us back to Justice Breyer. If he retires during the first two years of the Biden administration, his successor would not change the political balance on the court. There still would be six Republican-appointed justices and three Democratic-appointed justices. But that does not mean that even with confirmation of a like-minded justice, Justice Breyer’s departure would have no effect.

Justice Breyer is a staunch pragmatist. During oral arguments, he is often the only justice who questions the lawyers about the practical consequences of the court ruling one way or another—not only consequences for citizens but for the nation’s governing institutions. The court, he has often said, has a role in making democracy work.

He is a liberal, but more willing as a pragmatist to look for what he has called “the play in the joints” of court deliberations for where there may be common ground and compromise. He has said that when the justices meet in their private conference to discuss cases, “You have to listen really hard” to each justice to search for that play in the joints. Sometimes it is there; sometimes it is not.

The period after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia was a good example of his pragmatism and willingness to compromise. He and Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. and Justices Anthony Kennedy and Elena Kagan worked hard together to reach narrow decisions that drew majority votes and saved the court from frequent 4-4 deadlocks.

The three Democratic-appointed justices are likely to find themselves often in dissent on issues dear to liberal-minded groups unless they can persuade two of their conservative colleagues to join them. With the death of Justice Ginsburg, Justice Breyer, when the three are in dissent, is the senior justice with the right to write the major dissent or assign it to one of the others. Like Ginsburg, he sees value in dissents. They hold the majority’s feet to the fire, he has said, by forcing it to address the dissent's arguments and they are the seeds of majority decisions someday.

So what will Justice Breyer do? Will he or won’t he retire this year as predicted? Only he knows.

Marcia Coyle is a regular contributor to Constitution Daily and the Chief Washington Correspondent for The National Law Journal, covering the Supreme Court for more than 20 years.