One of the more recent changes to the Constitution is its 25th Amendment, which was ratified in 1967. The amendment deals with two serious situations not totally considered by the founders: vacancies in the office of the presidency, and the process to follow when a president suffers a disability or inability, and may not be able to perform their presidential duties.

The Constitution as ratified on June 21, 1788, contained broad language about presidential succession and disability under Article II, Section 1, Clause 6, the original Succession Clause:

The Constitution as ratified on June 21, 1788, contained broad language about presidential succession and disability under Article II, Section 1, Clause 6, the original Succession Clause:

“In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President, and such Officer shall act accordingly, until the Disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.”

Vacancies in Office

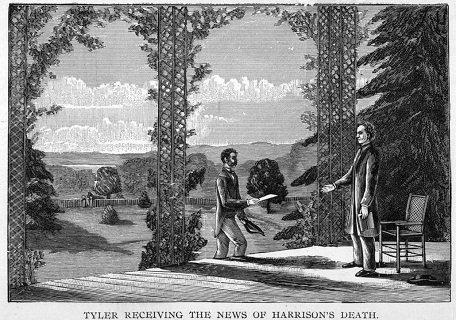

The Succession Clause was first tested on April 4, 1841, when President William Henry Harrison died in office. Vice President John Tyler arrived in Washington two days later and met with Harrison’s cabinet. Some cabinet members referred to Tyler as a “Vice President, acting as President,” as more of a temporary substitute and questioned the need for a new election.

Whig party leader Daniel Webster’s relayed his concerns to Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, but Taney declined to intervene in the matter, so as not “to intrude into the affairs which belong to another branch of government.” Tyler settled the issue by taking the presidential oath in front of Harrison’s cabinet in what became known as the “Tyler Precedent.” But some political leaders refuse to accept Tyler as the actual president, calling him “his accidency” and addressing Tyler as the vice president.

Interactive Constitution: Scholars Debate the 25th Amendment

Until 1967, the Tyler succession precedent was followed after the deaths of presidents in office—including less than a decade later when Vice President Millard Fillmore succeeded President Zachary Taylor after he died in office—and created a norm that the vice president had the full powers of the president when he assumed office.

The original Succession Clause also did not have a process for appointing and confirming a new vice president. Before 1967, the office of vice president became vacant 16 times due to deaths, resignations, and assumptions of the president’s office. And in several cases, the offices of president and vice president nearly became vacant simultaneously during a presidential term. In such a situation, an act of Congress in effect decided if the Secretary of State, Speaker of the House, or the Senate president pro tempore would serve as president if needed.

The 25th Amendment’s first two sections settle those problems. The amendment makes it clear the vice president becomes president “in case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation.” It also allows the president and Congress to nominate and approve a new vice president when that office becomes vacant.

Presidential Inability or Disability

The original Article II contained vague language about cases where the president might suffer a “inability” or “disability.” Starting with George Washington, who had a serious health scare as president, throughout history there have been cases where the chief executive may have been “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” Woodrow Wilson and Grover Cleveland had serious health problems while holding office. James Garfield was incapacitated for months after he was shot by an assassin and later died in office. Franklin Pierce, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Dwight D. Eisenhower also struggled with health issues.

To address these situations, the 25th Amendment’s third and fourth sections deal with scenarios where a president may suffer from or be judged to have an “inability” or a “disability.”

Section 3 starts with the president’s voluntary transfer of power and allows the president to notify Congress that he has designated the vice president to act as president until the president is able to resume work. This has happened after 1967 when presidents have told Congress the vice president would be acting as president while they were under general anesthesia for medical procedures.

Section 4, however, provides for an involuntary transfer of power, which permits the vice president and either the cabinet or a body approved “by law” formed by Congress, to jointly agree that “the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.”

Senator Birch Bayh, who played a critical role in championing the 25th Amendment, explained in February 1965 that Section 4 was designed to deal with “an impairment of the president’s faculties, meaning that he is unable either to make or communicate his decisions as to his own competency to execute the powers and duties of his office.”

Representative Richard Poff, another framer of the 25th Amendment, said in April 1965 that Section 4 could be invoked if the president “by reason of some physical ailment or sudden accident is unconscious or paralyzed and therefore unable to make or to communicate the decision to relinquish the powers of his Office,” or if the president suffered a “mental debility” and “is unable or unwilling to make any rational decision, including particularly the decision to stand aside.”

A majority of current or acting heads of 15 cabinet positions would need to agree with the vice president to invoke the 25th Amendment. The other potential option, a disability review panel, would need to be established by a statute that is signed by the president, or if vetoed, approved by two-thirds of the House and Senate. Such a panel is not currently established.

The 25th Amendment sets a high bar to use Section 4. Once the vice president and either the cabinet or a disability review panel agree to invoke the amendment, the vice president is allowed immediately to “assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.” The president can then notify Congress that “no inability exists” and he “shall resume the powers and duties of his office.” In that case, he can resume the powers of office unless the vice president and the cabinet or body formed by Congress jointly object.

If not in session, Congress is required to convene within 48 hours once the 25th Amendment is invoked. When in session, Congress has 21 days to settle the question if the president notifies Congress in writing that no inability exists. The vice president and the cabinet or disability body has four days to file an objection to the president’s declaration within that 21-day time frame. If no objection is filed, the president resumes his duties.

If the president’s declaration is contested, two-thirds of the House and Senate must agree to allow the vice president to act as president until the president is considered able to serve, and the president can file another declaration about his ability to serve after Congress votes on the question.

Editor’s note: Several sections of this post appeared in similar background posts from the author in Constitution Daily published in 2020 and 2021.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.