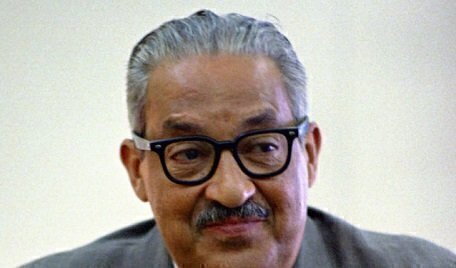

On January 24, 1993, retired Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall died at the age of 84. Marshall was one of the best-known litigators of his generation, and the Court’s first African-American member.

Marshall had been in failing health in the months before his death in Maryland, but he had hoped to give the vice-presidential oath to Al Gore just days before his passing.

The Supreme Court approved a special resolution honoring Marshall the following November. “The great majority of Supreme Court Justices are almost always remembered for their contributions to constitutional law as a member of this Court. Justice Marshall, however, is unique because his contributions to constitutional law before becoming a member of the Court were so significant,” said Chief Justice William Rehnquist.

The Chief Justice also shared a perspective of how the other Justices viewed Marshall behind closed doors. “We who sat with him during the time on the Court learned to value his wise counsel in Conference. We also looked forward to those occasions on which he would recount some of his experiences as a civil rights lawyer in often bitterly hostile towns and distinctly unfriendly courtrooms,” Rehnquist said. “Many of these stories had a humorous twist to them, but they also gave us a sense of what he had been up against in many of his cases. His forays to represent his clients required not only diligence and legal skill, but physical courage of a high order.”

Born as the great-grandson of an enslaved person, Marshall went through the public school system and received his law degree in 1933 from Howard University. As a long-time civil rights litigator for the NAACP, Marshall had won most of the cases he had argued in front of the Supreme Court in that capacity.

Arguably his biggest win was the case of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), one of the truly landmark decisions in the Court’s history that invalidated the concept of legal segregation at public schools. “This Court should make it clear that that is not what our Constitution stands for,” Marshall argued successfully.

But as Rehnquist pointed out in the resolution, Marshall won three other major civil rights cases at the Court before Brown: Smith v. Allwright, Shelley v. Kraemer, and Sweatt v. Painter. “These efforts alone would entitle him to a prominent place in American history had he never entered upon judicial service,” Rehnquist said.

On August 30, 1967, the Senate confirmed Marshall as the first African-American to serve as a Supreme Court Justice. He was confirmed in a 69-11 floor vote to join the Court. Marshall had won approval in two past Senate votes when Marshall was confirmed as a federal judge in the Kennedy administration and then as Solicitor General for President Lyndon Johnson. Marshall’s confirmation hearing was met with some resistance from Southern Senators who were concerned about his liberal track record.

On the Court, Marshall was a member of the bench’s liberal wing. He argued against the death penalty in two significant decisions, through his concurrence in Furman v. Georgia and his dissent Gregg v. Georgia. Marshall served 24 years on the Court before retiring in 1991. Clarence Thomas was nominated and later confirmed to replace Marshall.

Marshall said in June 1991 it was his health and not dissatisfaction with the Court’s conservatives that led to his retirement. At a press conference, a reporter asked Marshall how he wanted to be remembered. His response: as a person who “he did what he could with what he had.”