The Electoral College is a uniquely American institution and no stranger to controversy. But legally contested presidential elections within its system are not the norm for a part of the Constitution that dates back to 1787.

However, in 2020 the possibility of a contested presidential election has been discussed, at least among academics, for months. One factor is the spate of lawsuits involving voting by mail options related to the COVID-19 crisis. According to the Election Law Blog, at least 300 lawsuits were in play as of September 28 related to COVID-19 election issues, ranging from disputes about the postal service to deadlines to witness requirements.

However, in 2020 the possibility of a contested presidential election has been discussed, at least among academics, for months. One factor is the spate of lawsuits involving voting by mail options related to the COVID-19 crisis. According to the Election Law Blog, at least 300 lawsuits were in play as of September 28 related to COVID-19 election issues, ranging from disputes about the postal service to deadlines to witness requirements.

How rare are contested presidential elections? In the 58 presidential elections held since 1789, only three presidents have been elected after the regular Electoral College process played out. The 1800 and 1824 elections were contingent elections in Congress after no candidate won a majority of electoral college votes, and a special 15-person commission decided the disputed 1876 election. (In 1837, the Senate also decided a vice presidential race in a contingent election.)

In recent times, the Supreme Court ruling in Bush v. Gore in 2000 settled a controversy over an automatic recount in Florida that gave George Bush a majority of votes heading into the Electoral College proceedings that December.

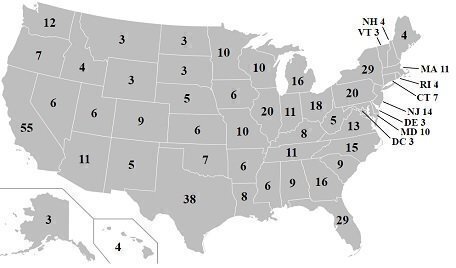

The Founders crafted the Electoral College as a compromise that balanced population-based voting and state interests when it came to electing a president and vice president. Each state is allocated a slate (or number) of electors based on its representation in Congress, and voters in each state choose electors affiliated with a political candidate.

With the exception of two states, all electors in each state are awarded to the candidate with the most popular votes. In turn, the electors of all states meet as a group (or college) at selected locations in December within each state (and the District of Columbia) to cast their votes. If a candidate has at least 270 electoral votes, they are declared the winner of the presidential election. If not, Congress can decide the issue under the 12th Amendment in a contingent election held after the newly elected Congress is seated in office.

The dramatic 1876 contest between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel Tilden is perhaps the closest the nation has come to experiencing a constitutional crisis related to presidential elections - and one law related to the 1876 dispute keeps popping up in scenarios linking that election to the 2020 contest.

After Election Day in 1876, four states, Florida, Oregon, Louisiana, and South Carolina, sent two different slates of electors to Congress to be counted, since there were rival Democratic and Republican factions in those states at the end of the post-Civil War Reconstruction period.

Live Online Program Alert

FREE AND FAIR WITH FRANITA AND FOLEY LIVE: THE CONTESTED ELECTION OF 1876

Monday, October 12, 6:30 p.m. EDT

Free online

Don't miss a live podcast recording of Free and Fair with Franita and Foley. Election scholar Michael Morley of Florida State University College of Law will join hosts Edward Foley and Franita Tolson for a discussion about one of the most contentious presidential elections in American history—the 1876 Hayes-Tilden election—and its significance today. Jeffrey Rosen, president and CEO of the National Constitution Center and host of the Center's We the People podcast, moderates.

No one had taken into account the scenario of disputed electors at a state level, and there were disagreements about how the dispute would be settled within Congress. Also, violence about the 1876 election outcome was a distinct possibility. In response, Congress passed the Electoral Commission Act in January 1877 to establish a special commission of 15 people to decide the election, with five members of the Senate, the House, and the Supreme Court on the panel.

The final and 15th vote on the commission was expected to be Supreme Court Justice David Davis, an independent. However, Davis resigned from the Court and his replacement was Justice Joseph P. Bradley. The commission awarded all 20 disputed electoral votes to Hayes, with Bradley voting with the Republicans. Hayes won the general election by one electoral vote just one day before he took his oath of office. In 1887, Congress then passed the Electoral Count Act to deal with a future scenario of rival or contested electoral votes presented at the joint session of Congress required under the 12th Amendment to certify election results.

The previously obscure Electoral Count Act could be a factor under certain conditions in the current election, some scholars have argued. One problem could be delays in counting votes submitted by mail at the state level, which could lead to a dispute about which votes are counted. Another factor could be lawsuits related to when vote counting ends, to meet the federal deadline for submitting electoral votes to Congress. Or there could be rival sets of electors sent to Congress if state legislatures and governors do not agree on a slate of electors.

A group of leading election scholars remarked in April 2020 a project sponsored by the University of California, Irvine School of Law, about the possible problems with the act.

“Scholarship both old and new has recognized the inadequacies of the Electoral Count Act in the event that a disputed presidential election reaches the joint session of Congress required by the Twelfth Amendment for the receiving and counting of Electoral College votes from the states,” the group said. “The statute is a morass of ambiguity, which is the exact opposite of what is required in this situation.”

The Constitution provides that the settlement of presidential election disputes first happens within the state legal system under powers granted by Article 2, Section 1. In a 2016 analysis of presidential election disputes, the Congressional Research Service said that “under the United States Constitution, these elections for presidential electors are administered and regulated in the first instance by the states, and state laws have established the procedures for ballot security, tallying the votes, challenging the vote count, recounts, and election contests within their respective jurisdictions.”

Of course, that litigation process within the states may involve rulings from the United States Supreme Court, as in Bush v. Gore from 2000. In the end, each state must send a certified list of presidential electors to Congress after the electors meet within each state if the state wants its votes counted in the presidential election.

Under another federal law (3 U.S. Code § 5) known as the safe harbor provision, a state must determine its electors six days before the Electoral College members meet in person. In 2020, that deadline is December 8, since the college votes on December 14. Back in 2000, a deeply divided Supreme Court, in a 5-4 vote, wouldn’t allow an extension of the safe harbor deadline proposed by Justice Stephen Breyer in the specific case of Florida’s recount.

Federal statutes also require states to deliver certified electoral college results to the vice president, serving as president of the Senate, and other parties by the fourth Wednesday in December; in the year 2020 that date falls on December 23. If the certificates and documents are not received, the Vice President requests the results shall be sent to Congress by registered mail or messenger.

Also under federal law, the joint session of Congress required by the 12th Amendment to count the electoral votes and declare the winners of the presidential election is held on January 6, 2021. That is when the Electoral Count Act becomes a factor. When the results from each state are announced, a member of the House and Senate can jointly object, in writing, to the election results from that state. The House and Senate then adjourn briefly to consider the objection; if both bodies agree to uphold the objection, the votes are excluded from the election results under the terms of the Electoral Count Act.

But what happens if a state provides a second slate of electors named by its legislature or a state’s governor refuses to sign the state’s election certificate in a dispute over ballot counting? Ned Foley, a constitutional election scholar from the Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, has written extensively about such scenarios.

“The procedures for handling a disputed presidential election that reaches Congress are regrettably, and embarrassingly, deficient,” Foley wrote in 2019 for the Loyola University Chicago Law Journal. The Electoral Count Act of 1887, which Foley calls “astonishingly messy,” could lead to competing interpretations within Congress of what actions it can take on January 6. Foley also notes there are some historical arguments parts of the Electoral Count Act of 1887 that are unconstitutional and there could a role for the Supreme Court to settle these disputes before January 20, 2021, when the Constitution’s 20th Amendment requires the new President to take the oath of office.

In that scenario, the Speaker of the House would serve a president if Congress has not certified a winner of the 2020 presidential election and remain in that role until Congress does so.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.

For Further Reading

Congressional Research Service, The Electoral College: a 2020 Presidential Election Timeline (September 3, 2020), https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/2020-09-03_IF11641_5002793d090fd38c1af7284b97317d97259d009f.pdf

Congressional Research Service, Legal Processes for Contesting the Results of a Presidential Election (October 24, 2016), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44659.pdf

Foley, Edward B., Preparing for a Disputed Presidential Election: An Exercise in Election Risk Assessment and Management (August 31, 2019). 51 Loyola University Chicago Law Journal 309 (2019), Ohio State Public Law Working Paper No. 501, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3446021

UC Irvine School of Law, Fair Elections During a Crisis: Urgent Recommendations in Law, Media, Politics, and Tech to Advance the Legitimacy of, and the Public’s Confidence in, the November 2020 U.S. Elections (April 2020), https://law.uci.edu/2020ElectionReportLAWPOLITICSMEDIATECH