The Supreme Court has ruled on an important test first posed by Justice William Brennan nearly 40 years ago about property rights, as Justice Anthony Kennedy sided with the Court's four liberal Justices on Friday.

In 1978, Brennan wrote for a 6-3 majority in the Penn Central v. New York City case that redefined property rights under the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause and also served as a foundation for historic preservation programs at a local level.

In 1978, Brennan wrote for a 6-3 majority in the Penn Central v. New York City case that redefined property rights under the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause and also served as a foundation for historic preservation programs at a local level.

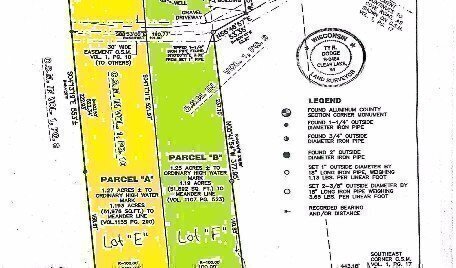

The current case in front of the Court, Murr v. Wisconsin, didn't involve a glamorous property such as Grand Central Station, the subject of Brennan’s opinion. Instead, the dispute was about a vacant vacation property, and if the parcel was part of a combined lot, or a parcel on its own.

On Friday, the majority 5-3 opinion written by Kennedy sided with the state of Wisconsin in the dispute, saying the test devised by Brennan was properly applied by the state, but that the courts also needed to include more than just Brennan's test in deciding similar disputes.

"The governmental action was a reasonable land-use regulation, enacted as part of a coordinated federal, state, and local effort to preserve the river and surrounding land," Kennedy said. "Like the ultimate question whether a regulation has gone too far, the question of the proper parcel in regulatory takings cases cannot be solved by any simple test. ... Courts must instead define the parcel in a manner that reflects reasonable expectations about the property."

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the dissent. "State law defines the boundaries of distinct parcels of land, and those boundaries should determine the 'private property' at issue in regulatory takings cases. Whether a regulation effects a taking of that property is a separate question, one in which common ownership of adjacent property may be taken into account," he said.

The Murr family has owned two riverfront lots since the 1960s; one of the lots contained a vacation cottage; the other lot wasn’t developed. One lot was in the parent’s name while the other was in the name of a company owned by the family. The two lots were jointly conveyed to four of their children in 1994 and 1995.

In 2004, when the children began to explore selling the empty lot to pay for improvements in the cottage, they found out that a zoning law established in 1975 barred the children from selling the empty lot separate from the cottage because two adjoining lots were now owned by one entity. The zoning law also prohibited the development of the empty lot because it didn’t meet minimum size requirements for an independent lot.

The dispute in front of the Supreme Court involved a concept called a “parcel as a whole.” In 1978, Brennan fashioned that test as part of the Penn Central decision.

A New York City commission prohibited the Penn Central Railroad from redeveloping Grand Central Station after two plans substantially changed the building’s historic look above the building. Penn Central sued, claiming it should receive full compensation for the air rights about Grand Central Station.

Brennan and the majority disagreed, saying the commission’s decision wasn’t a taking under the Fifth Amendment and that the railroad still could derive a reasonable economic return from the building’s use. The decision established a four-part test to determine if a property holder should receive “just compensation” under the Fifth Amendment if a government policy or action results in a taking of their property.

One of the four parts was called the “parcel of a whole.” Brennan said that “this Court focuses rather both on the character of the action and on the nature and extent of the interference with rights in the parcel as a whole—here, the city tax block designated as the ‘landmark site.’” In that context, the Court said the Grand Central building and the air space above it was one property in terms of the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause.

The Murr family’s lawyers cited another landmark Supreme Court decision, Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council (1992), to support their claim that they should be able to sell the property or seek compensation from the government.

The Lucas decision said that the denial of all economic use of a property by a government regulation was a taking under the Fifth Amendment and required just compensation. The Wisconsin government has argued that the properties should be considered as a “whole” in the takings analysis, citing the Penn Central decision. The state appeals court ruled against the Murr family and the family filed an appeal with the Supreme Court, which was accepted in January 2016.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.