Some of the most significant Supreme Court cases in history were controversies that were started by, or on behalf, of public school students or teenagers. Here is a brief review of eight such cases.

Compelled free speech by public schools

Compelled free speech by public schools

Two early but important Supreme Court cases defined the ability of students to not take part in some public school activities based on First Amendment religious objections. First, in the 1940 case of Minersville School District v. Gobitis, children Lillian Gobitas (age 12) and William Gobitas (age 10) were expelled from their Pennsylvania public school for not participating in the Pledge of Allegiance. Their father sued the school district because their family affiliation with the Jehovah's Witnesses prevented oath taking to any flag. The Court ruled for the school district in 1940 but that decision only lasted about three years, when the Justices reversed themselves in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette. Jehovah's Witnesses grade-school students Gathie (age 10) and Marie Barnett (age 8) were expelled from their public school for refusing to pledge. This time, Justice Robert Jackson, in a 6-3 decision, said the students’ First Amendment rights were violated.

Segregated public schools

The Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) decision actually consolidated lawsuits from four states into one case including Briggs v. Elliott was from South Carolina; Davis v. County School Board was from Virginia; and Gebhart v. Belton from Delaware. Oliver Brown, on behalf of his nine-year-old daughter Linda, challenged a Kansas state law that permitted public schools segregated by race. The Warren Court’s unanimous decision explained that the separate-but-equal doctrine from the 1896 Plessey decision violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, and it ordered an end to legally mandated race-segregated schools.

Compelled religious prayers in public schools

The Schempp family, including high school students Roger and Donna Schempp, sued the Abington (Pa.) school district over its policy of including bible verses and prayers at school activities. The Schempps were Unitarians, and they sued the school, even though it allowed for written exemptions for students objecting to the practice. In Abington School District v. Schempp (1963), Justice Fred Clark said the general practice violated the First Amendment. “While the Free Exercise Clause clearly prohibits the use of state action to deny the rights of free exercise to anyone, it has never meant that a majority could use the machinery of the State to practice its beliefs,” Clark said.

Due process rights for teenagers

In 1968, the Court ruled in an 8-1 decision in the case of In re Gault that teens accused of crimes are entitled to the same due process rights as adults. In 1964, Jerry Gault, 15, was taken into custody for allegedly making an obscene phone call. Gault was held in custody since he was on probation for another incident and his parents weren’t initially notified. A judge then committed Gault to six years in custody for a crime that had an adult sentence of two months. Justice Abe Fortas said the juvenile detention and trial practices used by the state of Arizona widely violated due process clauses under the 14th Amendment and Fifth Amendment.

Political free speech for students

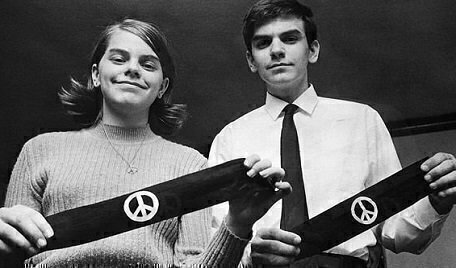

At the height of the Vietnam War, Mary Beth Tinker, a 13-year-old student at Warren Harding Junior High School in Des Moines, Iowa, wore a black armband to school to protest the Vietnam War and was suspended. A few other students joined her. In the 7-2 majority opinion in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), Justice Fortas said public school students don’t “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” While Fortas said these rights don’t extend to conduct that “materially disrupts classwork or involves substantial disorder or invasion of the rights of others,” Tinker’s silent protest was permitted under the First Amendment.

Mandatory school attendance and faith

In Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), Wisconsin mandated that all children attend public school until age 16, but members of the Old Order Amish religion and the Conservative Amish Mennonite Church refused to send their 14- and 15-year-old children to schools. They argued that the children didn’t need to be in school that long to lead a fulfilling life of farming and agricultural work, and such state-compelled laws violated their faith. The Supreme Court unanimously agreed, saying that the values of public school were in “sharp conflict with the fundamental mode of life mandated by the Amish religion.”

Student searches at school

The 1985 decision of New Jersey v. TLO found that public school students have some rights when it comes to school officials who want to search their person or personal belongs for evidence of wrongdoing. But those rights are very limited. In Piscataway, New Jersey, after a high school student (called “TLO” in court documents) was caught smoking cigarettes in school, she was confronted by the school’s vice principal, who forced the student to hand over her purse. The vice principal then searched her purse, found drug paraphernalia and called the police; the student was eventually charged with multiple crimes and expelled from the school. Her family argued that the evidence should not have been admissible in court because it violated T.L.O.’s Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable searches and seizures. The Supreme Court decided students have a legitimate expectation of privacy when in school, but school officials can conduct a “reasonable” search beyond a mere hunch, based on evidence, without a warrant.

Religious student clubs at public schools

Westside High School senior Bridget Mergens in Omaha, Nebraska, asked her principal for permission to start an after-school Christian bible, prayer and study student club. The principal denied Mergens’ request, telling her that a religious club would violate the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause. In Board of Education of Westside Community Schools v. Mergens (1990), Sandra Day O’Connor in an 8-1 decision said that since the club didn’t study school curriculum, it was permitted under the Equal Access Act, which allows student access to any similar club based on Free Speech principles. “The school has maintained a ‘limited open forum’ under the Act and is prohibited from discriminating, based on the content of the students' speech, against students who wish to meet on school premises during noninstructional time,” O’Connor said.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.