Federal and state judges these days are finding a new assignment: reading up on what the Supreme Court once called “the infamous history of bills of attainder.” A federal judge in Sherman, Texas, is going to be doing that soon, and there is a real prospect that a judge in New York State will also be doing so shortly.

By coincidence, the Trump Administration’s lawyers are trying to thwart a Chinese telecom company’s challenge to a federal law that the company calls a “bill of attainder,” while personal lawyers for President Trump are expected to be making a similar challenge in a separate case to a measure that shortly will become a state law in New York.

By coincidence, the Trump Administration’s lawyers are trying to thwart a Chinese telecom company’s challenge to a federal law that the company calls a “bill of attainder,” while personal lawyers for President Trump are expected to be making a similar challenge in a separate case to a measure that shortly will become a state law in New York.

The Chinese firm Huawei is challenging a new federal law seeking to thwart suspected Chinese government manipulation of software used by federal agencies, while President Trump’s personal team seems poised to challenge a just-passed state law affecting disclosure of his personal and business tax records.

Both cases appear likely to be significant tests of the concept of a “bill of attainder.” Those have been defined by the Supreme Court as actions of legislatures (federal or state) that single out a specific individual (or entity), declare that person or entity to be guilty, and impose punishment – all without a court trial. The Court has been examining bills of attainder since 1810 and the time of Chief Justice John Marshall to define how these kinds of legislation that would fit into the forbidden category.

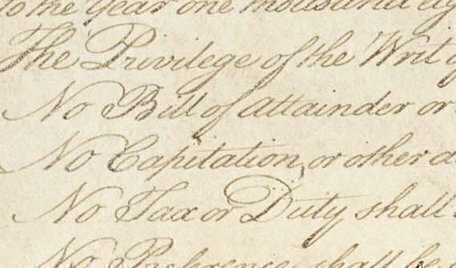

Since 1787, the Constitution has contained a clause – not further defined – saying simply that “no bill of attainder…shall be passed.” That clause probably was originally aimed at barring Congress from passing such a bill, since it is contained in a long list of clauses dealing with congressional powers. The Supremacy Clause in Article VI also means that the ban applies to state legislatures, too. In fact, two of the Supreme Court’s most significant precedents on the clause’s meaning, issued in 1867 and still followed, involved a state law in Missouri as well as a federal law requiring a loyalty oath of former supporters of the Confederacy during the Civil War.

The concept of “attainder” by legislation dates back at least to 16th Century England. Traditionally, it was used by Parliament to single out and punish – often, by death -- the political enemies of the crown. Some of America’s pre-constitutional colonies followed the practice to punish individuals loyal to the English crown, but those who wrote the Constitution in Philadelphia in 1787 were determined to forbid the practice and did so as part of Article I.

The Supreme Court once remarked that the clause was “an important bulwark against tyranny.”

Since the likelihood today is that the two highest-profile cases testing new laws as forbidden “bills of attainder” both involve President Trump or his Administration in one way or another, it is useful to note that the Supreme Court went the furthest to spell out the meaning of the clause in a famous decision in 1977, Nixon v. Administrator Of General Services, involving another President, Richard M. Nixon.

Reacting to the Watergate scandal which had led to Nixon’s resignation from the presidency in 1972, Congress two years later passed a presidential records law that, for the first time in U.S. history, overturned the long-standing view that a President’s records were the personal, private property of the occupant of the office.

The law gave the federal government control of the famous Nixon White House audiotapes and some 138 boxes of Nixon’s documents and papers. That overturned an agreement that a government agency had made with Nixon that would have allowed him, later on, to destroy the tapes. Nixon was given access to the materials, but they belonged to the government.

Among other unsuccessful constitutional challenges to the law, Nixon’s lawyers claimed that it was a bill of attainder, punishing him for what Congress saw as the wrongs of the Watergate scandal. In its decision, by a vote of 7-to-2, the Court declared that the clause was meant to apply only to a legislative measure that (1) actually singled out an identified individual or group, (2) imposed a form of punishment, and (3) barred any trial in court of that individual or group for the alleged wrongdoing.

In applying those three tests, the Court told lower courts to take into account the history of punishment that was traditionally forbidden or strictly limited, to look at whether the legislators passing such a bill were motivated to punish, and to determine whether the measure served a legislative goal other than punishing the specified individual or group.

Since March 2019, that 1977 precedent has been undergoing a new review in the Sherman, Texas, court of U.S. District Judge Amos T. Mazzant III in a case filed by Huawei Technologies, USA. That is the U.S. affiliate of the Chinese telecom giant, Huawei.

The lawsuit, in which Trump Administration lawyers are scheduled to file in July a formal motion to dismiss, raised several constitutional challenges to a defense authorization bill passed last year by Congress that imposes a ban on federal government agencies using Huawei electronic equipment and devices and a ban on those agencies doing business with users of those supplies. The law was prompted by worries in Congress that Huawei was essentially a part of the Chinese military and was likely to use those devices, when installed in government facilities, as a way to manipulate software in ways that are harmful to U.S. defense and commerce.

The bill of attainder claim is the first and most prominent of Huawei’s constitutional arguments.

Since that lawsuit was filed, President Trump has issued an executive order declaring a national emergency in the telecom field, further isolating Huawei from U.S. business opportunity. That order is clearly targeting Huawei and it is being applied by the Commerce Department to the Chinese company and 70 of its affiliates. So far, that presidential order has not become a part of Huawei’s lawsuit in Texas, but no doubt will become part of the evidence supporting the basic claim that the company is being singled out unconstitutionally.

The next lawsuit that seems likely to be filed, and quite soon, would challenge a measure that cleared the New York legislature on Wednesday, and it is expected to be signed into law promptly by Governor Andrew Cuomo.

That measure was challenged throughout the legislative session by supporters of President Trump, including some Republican legislators, who argued that it will impose punishment on President Trump alone, and thus is an unconstitutional bill of attainder.

The law as passed by the legislature would authorize New York state officials to turn over to any of three committees of Congress the state tax returns filed by the President and his businesses that are headquartered in New York. The measure provides that a congressional committee must first attempt to obtain Trump’s federal tax returns from the U.S. Treasury, and can then seek the state returns from New York officials.

President Trump and his associates have refused to obey subpoenas to turn over to congressional committees six years of the President’s federal returns. State returns probably contain much of the same information, and thus could supply at least some of what a congressional panel has been unable to obtain from the Treasury.

Because of the President’s strong resistance to disclosure of his personal and business records, it is generally expected that the New York law will be tested in court as soon as it becomes law with the governor’s signature.

An initial move probably would be a plea to put the state law on hold while the legal challenge proceeds. The bill of attainder claim could be put forth in a lawsuit either in federal or state court since both have authority to apply constitutional provisions.

Lyle Denniston has been writing about the Supreme Court since 1958. His work has appeared here since mid-2011.