The recent pardon and clemency orders issued by President Donald Trump are reviving an enduring debate about the executive’s pardon powers granted under the Constitution.

On February 18, 2020, President Trump granted four clemency orders (including one for former Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich) and seven pardons (including grants to financier Michael Milken, former New York City police chief Bernard Kerik, and businessman Edward DeBartolo Jr.).

On February 18, 2020, President Trump granted four clemency orders (including one for former Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich) and seven pardons (including grants to financier Michael Milken, former New York City police chief Bernard Kerik, and businessman Edward DeBartolo Jr.).

In recent years, similar questions arose about pardons issued by Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush, and a prospective pardon for former government contractor Edward Snowden.

Here is a brief explanation of the president’s clemency powers, and a look at some past cases and controversies.

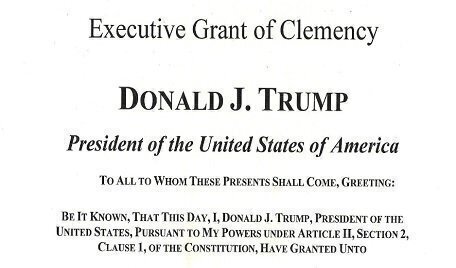

The president has pardon or clemency power under Article II, Section 2, Clause 1, of the Constitution, under the Pardon Clause. The clause says the president “shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” While the president’s powers to pardon seem unlimited, a presidential pardon can only be issued for a federal crime, and pardons can’t be issued for impeachment cases tried and convicted by Congress.

The Office of the Pardon Attorney, which is part of the Justice Department, has handled such matters for the President since 1893, and it has a detailed description of the pardon and clemency process on its website.

The Congressional Research Service’s January 2020 report on presidential pardon powers lists five types of clemency that fall under the President’s powers. A full pardon relieves a person of wrongdoing and restores any civil rights lost. Amnesty is similar to a full pardon and applies to groups or communities of people. A commutation reduces a sentence from a federal court. A president can also remit fines and forfeitures and issue a reprieve during a sentencing process.

The CRS says the courts and Congress have a very limited role in the pardon process. In a 1974 decision of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, Hoffa v. Saxbe, the court said the president has “unfettered executive discretion” to grant clemency. The Hoffa case involved conditions placed by President Richard Nixon on a commuted sentence for the former Teamster’s leader, Jimmy Hoffa, barring him from resuming a union leadership position. Hoffa argued the stipulation violated his First Amendment rights. Judge John H. Pratt said the stipulations were reasonable. That court’s definition of reasonableness has not been tested at the Supreme Court, the CRS says.

President Nixon was also involved in perhaps the most famous presidential pardon, when President Gerald Ford pardoned Nixon for any crimes Nixon might have committed during the Watergate scandal, even though Nixon wasn’t charged with or convicted of federal crimes. (This is known as a pre-emptive pardon.) Nixon was able to receive a pardon under the precedent of the 1866 Supreme Court’s decision in Ex parte Garland, which allowed for a pardon granted by President Andrew Johnson to remain in force for a former Confederate politician. Other notable pre-emptive pardons include President George H.W. Bush’s pardons of former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger and former CIA official Duane Clarridge in late 1992 before they were tried on Iran-contra Affair charges.

The Ex parte Garland decision also make it clear that Congress did not have the direct power to intervene in the presidential pardon process. “Congress can neither limit the effect of his pardon, nor exclude from its exercise any class of offenders. The benign prerogative of mercy reposed in him cannot be fettered by any legislative restrictions,” said Justice Stephen Johnson Field in his majority opinion.

Other recent examples of high-profile clemencies include President Barack Obama’s commutation of a jail sentence for Wikileaks figure Chelsea Manning; President Bill Clinton’s pardon of his own brother, Roger (who had served a one-year jail sentence on a drug conviction); and President Ronald Reagan’s pardon of New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner for charges related to illegal campaign contributions made to Nixon’s presidential campaign. Each act of clemency was met with some public criticism of the presidential pardon power.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.