It is the season for controversy about public holiday displays, and this year’s stories include a fight over a cross in Missouri and some relocated Nativity scenes.

The First Amendment's Establishment Clause prohibits government from sponsoring or endorsing religious symbols. Since 2013, Constitution Daily has covered several disputes over what constitiutes a religious symbol in a December holiday context. Back then, a main dispute involved a Nativity scene or crèche at Florida’s Capitol in Tallahassee, and the move by state officials to exclude the Satanic Temple from it. But contributions to the display from the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster were allowed, along with a Festivus pole.

The First Amendment's Establishment Clause prohibits government from sponsoring or endorsing religious symbols. Since 2013, Constitution Daily has covered several disputes over what constitiutes a religious symbol in a December holiday context. Back then, a main dispute involved a Nativity scene or crèche at Florida’s Capitol in Tallahassee, and the move by state officials to exclude the Satanic Temple from it. But contributions to the display from the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster were allowed, along with a Festivus pole.

In 2014, TV host Bill O’Reilly waged his own war against “the war on Christmas,” and the Satanic Temple won fights to get its exhibits at state public holiday displays in Florida and Michigan.

In 2015, the Freedom From Religion Foundation installed its Bill of Rights Nativity scene in several public locations. The next year, a dispute involved a Charlie Brown Christmas Special display in a public school that features a Biblical message from the classic TV special.

And last year, a federal judge ruled against Texas Governor Greg Abbott after Abbott had ordered the removal of the Bill of Rights Nativity scene from the state capitol.

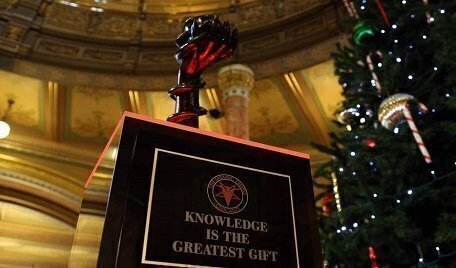

So far in 2018, a new “Snaketivity” display from a group related to the Satanic Temple is on display at the Illinois Capitol grounds, despite some protests. In Emmaus, Pennsylvania, a complaint from the Americans United For Separation of Church and State led to the relocation of a Nativity scene from a public library to a church. Similarly, the city of Woodland in Washington state moved its Nativity scene from a public park to private property.

Ozark, Missouri is the scene of a very public dispute over a large cross in its Finley River Park holiday display. The cross-shaped light display has stood in the park for the past 20 years, framed around a utility pole.

City officials said they received a complaint from Freedom From Religion Foundation about the cross display. On the advice of its attorney, Ozark said it would take down the cross, but officials changed their minds after a public outcry of support for the display. (Ozark is also located in Christian County, Missouri.)

And in Elmore, Ohio, residents came up with a constitutional solution to a similar complaint about a Nativity scene that had been on public property. In 2017, the city’s former mayor agreed to host the display on his lawn, which avoided potential legal action. This year, the Nativity scene is back at a public park with the addition of Santa Claus, the Little Drummer Boy, and Frosty the Snowman.

Elmore’s move is related to the Supreme Court’s Plastic Reindeer Rule precedent. In Lynch v. Donnelly (1984), the Court was asked to consider if the First Amendment prohibited Pawtucket, Rhode Island from including a Nativity scene in its annual Christmas display. The holiday display included a crèche along with other secular symbols such as a plastic reindeer, a Santa Claus house, and a Christmas tree.

Chief Justice Warren Burger allowed the crèche to stay at the exhibit. Court observers at the time saw the presence of the reindeer as broadening the purpose of the display.

Another holiday-related decision in 1989 clarified the Court’s position on crèches. In County of Allegheny v. American Civil Liberties Union, the Court said in a 5-4 decision that of two public-sponsored holiday displays in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, only one was permissible.

Inside a courthouse the county had set up a crèche with a banner that read "Glory to God for the birth of Jesus Christ." The Justices objected to that display. A second display outside the Allegheny County courthouse featured a menorah, a Christmas tree and a sign honoring Liberty. “We agree that the crèche display has that unconstitutional effect, but reverse the Court of Appeals' judgment regarding the menorah display,” said Justice Harry Blackmun.

An Endorsement Test advocated by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in the Lynch case played a critical role in the Allegheny case. And in her concurring Allegheny opinion, she stressed what she meant in Lynch.

“In Lynch, I concluded that the city's display of a crèche in its larger holiday exhibit in a private park in the commercial district had neither the purpose nor the effect of conveying a message of government endorsement of Christianity or disapproval of other religions,” O’Connor wrote. “The purpose of including the crèche in the larger display was to celebrate the public holiday through its traditional symbols, not to promote the religious content of the crèche.”

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.