In the face of future public health emergencies like the Coronavirus, a precedential Supreme Court decision about the government’s power to protect citizens by quarantine and forced vaccinations could receive new interest.

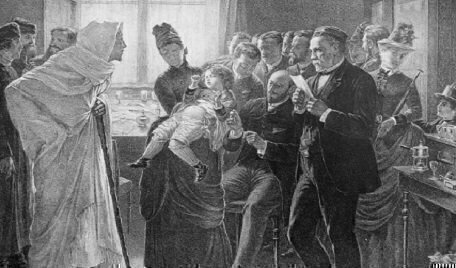

On February 20, 1905, the Supreme Court, by a 7-2 majority, said in Jacobson v. Massachusetts that the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts could fine residents who refused to receive smallpox injections. In 1901, a smallpox epidemic swept through the Northeast and Cambridge, and Massachusetts reacted by requiring all adults receive smallpox inoculations subject to a $5 fine. In 1902, Pastor Henning Jacobson, suggesting that he and his son both were injured by previous vaccines, refused to be vaccinated and to pay the fine. In state court, Jacobson argued the vaccine law violated the Massachusetts and federal constitutions. The state courts, including the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, rejected his claims. Before the Supreme Court, Jacobson argued that, “compulsion to introduce disease into a healthy system is a violation of liberty.”

On February 20, 1905, the Supreme Court rejected Jacobson’s arguments. Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote about the police power of states to regulate for the protection of public health: “The good and welfare of the Commonwealth, of which the legislature is primarily the judge, is the basis on which the police power rests in Massachusetts,” Harlan said “upon the principle of self-defense, of paramount necessity, a community has the right to protect itself against an epidemic of disease which threatens the safety of its members.”

Jacobson had argued that the Massachusetts law requiring mandatory vaccination was a violation of due process under the 14th Amendment, particularly the right “to live and work where he will” under the precedent of Allgeyer v. Louisiana (1897), a case that found that a state law preventing certain out-of-state insurance corporations from conducting business in the state was unconstitutional restriction of freedom of contract under the 14th Amendment. Harlan answered that while the Court had protected such liberty, a citizen:

[M]ay be compelled, by force if need be, against his will and without regard to his personal wishes or his pecuniary interests, or even his religious or political convictions, to take his place in the ranks of the army of his country and risk the chance of being shot down in its defense. It is not, therefore, true that the power of the public to guard itself against imminent danger depends in every case involving the control of one's body upon his willingness to submit to reasonable regulations established by the constituted authorities, under the sanction of the State, for the purpose of protecting the public collectively against such danger.”

The Court did not extend the rule beyond the facts of the case before it. Harlan ended his opinion by stating the limitations of the ruling: “We are not inclined to hold that the statute establishes the absolute rule that an adult must be vaccinated if it be apparent or can be shown with reasonable certainty that he is not at the time a fit subject of vaccination or that vaccination, by reason of his then condition, would seriously impair his health or probably cause his death.”

In the years following the case, the anti-vaccine movement mobilized and the Anti-Vaccination League of America was founded three years later in Philadelphia under the principle that “health is nature’s greatest safeguard against disease and that therefore no State has the right to demand of anyone the impairment of his or her health,” and aimed “to abolish oppressive medical laws and counteract the growing tendency to enlarge the scope of state medicine at the expense of the freedom of the individual.” The League warned about what it believed to be the dangers of vaccination and allowing the intrusion of government and science into private life,

When a separate question of vaccinations—state laws requiring children to be vaccinated before attending public school—came up in 1922 in Zucht v. King, Justice Louis Brandeis and a unanimous court held that Jacobson “settled that it is within the police power of a state to provide for compulsory vaccination” and the case and others “also settled that a state may, consistently with the federal Constitution, delegate to a municipality authority to determine under what conditions health regulations shall become operative.” More recently, in 2002, a federal district court declined to find a exemption to mandatory vaccinations laws for “sincerely held religious beliefs” or a fundamental right of parents to make decisions concerning medical procedures of their children.

The application of Jacobson to the modern age of vaccinations is a source of scholarly debate, with some arguing that the case no longer applies in an era in which vaccines like HPV are not medically necessary to prevent the spread of disease. But others maintain Jacobson’s importance today in providing ample power to protect the public health, especially with the threat of pandemics.

Nicholas Mosvick was a Senior Fellow for Constitutional Content at the National Constitution Center.