On February 24, 1803, Chief Justice John Marshall issued the Supreme Court’s decision in Marbury v. Madison, establishing the constitutional and philosophical principles behind the high court’s power of judicial review.

The dramatic tale begins with the presidential election of 1800, in which President John Adams, a Federalist, lost reelection to Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican. Congress also changed hands, with the Democratic-Republicans achieving majorities in both chambers.

The dramatic tale begins with the presidential election of 1800, in which President John Adams, a Federalist, lost reelection to Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican. Congress also changed hands, with the Democratic-Republicans achieving majorities in both chambers.

Adams and the Federalists could see the writing on the wall: the party’s power had been limited to the judicial branch. In a bid to strengthen Federalist power, President Adams appointed Secretary of State John Marshall to be Chief Justice of the United States. The Federalists, with weeks remaining in the lame-duck session, passed a new Judiciary Act—the “Circuit Court Act”—which expanded the jurisdiction of the circuit courts and created six new circuits with 16 new judicial seats. (The law also eliminated circuit duty for Supreme Court justices, and provided for easier removal of litigation from state to federal court.)

To fill the newly expanded judiciary, on March 1, 1801, three days before Jefferson’s inauguration, Adams stayed up late into the night signing commissions for the new judges, including the 42 new Justices of the Peace. The “midnight appointments,” as they came to be known, were also notarized by Marshall, still performing his secretarial duties. But the rush of presidential transition led to the administration’s failure to deliver several of those commissions, including that owed to William Marbury, who had been named a justice of the peace for the District of Columbia. On March 4, upon assuming the office of the presidency, Jefferson ordered Secretary of State James Madison not to deliver the commissions.

Marbury’s lost commission became a test case for the ousted Federalists who were outraged over the Democratic-Republican Congress’s repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801 and the passing of a replacement act in 1802, and who were hoping to test its constitutionality as soon as possible. Before the Supreme Court considered the case in February, Congress held a viciously partisan debate over the constitutionality of the Repeal Act, with Republicans claiming that the people were the final judges of the constitutionality of acts of Congress. Marbury, with representation from Adams’ Attorney General Charles Lee, demanded a writ of mandamus from the Supreme Court to obtain his commission.

In Marbury v. Madison, the Court was asked to answer three questions. Did Marbury have a right to his commission? If he had such a right, and the right was violated, did the law provide a remedy? And if the law provided a remedy, was the proper remedy a direct order from the Supreme Court?

Writing for the Court in 1803, Marshall answered the first two questions resoundingly in the affirmative. Marbury’s commission had been signed by the President and sealed by the Secretary of State, he noted, establishing an appointment that could not be revoked by a new executive. Failure to deliver the commission thus violated Marbury’s legal right to the office.

Marshall also ruled that Marbury was indeed entitled to a legal remedy for his injury. Citing the great William Blackstone’s Commentaries, the Chief Justice declared “a general and indisputable rule” that, where a legal right is established, a legal remedy exists for a violation of that right.

It was in the third part of the opinion that presented a dilemma: If Marshall decided to grant the remedy and order delivery of the commissions, he risked simply being ignored by his rivals, thereby exposing the young Supreme Court as powerless to enforce its decisions, and damaging its future legitimacy. But siding with Madison would have been seen as caving to political pressure—an equally damaging outcome, particularly to Marshall who valued the Court as a nonpartisan institution. The ultimate resolution is seen by many scholars as a fine balancing of these interests: Marshall ruled that the Supreme Court could not order delivery of the commissions, because the law establishing such a power was unconstitutional itself.

That law, Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, said the Court had “original jurisdiction” in a case like Marbury—in other words, Marbury was able to bring his lawsuit directly to the Supreme Court instead of first going through lower courts. Citing Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution, Marshall pointed out that the Supreme Court was given original jurisdiction only in cases “affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls” or in cases “in which a State shall be Party.” Had the Founders intended to empower Congress to assign original jurisdiction, Marshall reasoned, they would not have enumerated those types of cases. Congress, therefore, was exerting power it did not have.

This was an exercise of judicial review, the power to review the constitutionality of legislation. To be sure, Marshall did not invent judicial review—several state courts had already exercised judicial review, and delegates to the Constitutional Convention and ratifying debates spoke explicitly about such power being given to the federal courts. The Court itself in the 1796 case of Hylton v. United States reviewed and upheld an act of Congress as constitutional—with Alexander Hamilton arguing for the validity of the tax in question. And in Ware v. Hylton, the Supreme Court struck down a Virginia creditor law in conflict with the Treaty of Paris based on federal supremacy.

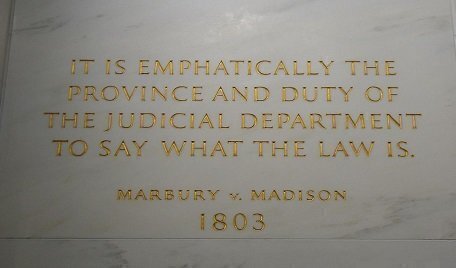

Still, the legendary Chief Justice applied judicial review firmly and artfully to the nation’s highest court. “It is emphatically the duty of the Judicial Department,” he wrote, “to say what the law is.” Until Marbury, judicial review was not widely accepted in cases of doubtful unconstitutionality and was not an aspect of ordinary judicial activity, and its scope was more modest. And while Marbury was not a particularly controversial decision in 1803, it has remained the source of scholarly debate.

In the short run, Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans got what they wanted: Marbury and the other “midnight appointments” were denied commissions. But in the long run, Marshall got what he wanted: A independent Supreme Court with the power of judicial review. As historian Gordon Wood eloquently put it, Marshall’s greatest achievement was not invented judicial review, but “maintaining the Court’s existence and asserting its independence in a hostile Republican climate.”

For more reading on the debate between scholars over the meaning of Marbury and its implication for judicial review and judicial supremacy, consider the following:

Bruce Ackerman, Failure of the Founding Fathers: Jefferson, Marshall, and the Rise of Presidential Democracy (Harvard University Press 2005)

Albert Beveridge, The Life of John Marshall (1919)

Edward S. Corwin, John Marshall and the Constitution: A Chronicle of the Supreme Court (1977)

Mark A. Graber, “Passive-Aggressive Virtues: Cohens v. Virginia and the Problematic Establishment of Judicial Power,” 12 Const. Comm. 68, https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/167160/12_01_Graber.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Charles Hobson, The Great Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Rule of Law (1996)

Michael J. Klarman, “How Great Were the ‘Great’ Marshall Court Decisions?” Va. L. Rev. (2001), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=270081

Larry Kramer, “Marbury and the Retreat from Judicial Supremacy,” 20 Const. Comm. 205 (2003), https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/183156/20_02_Kramer.pdf

Leonard W. Levy, Original Intent and the Framers Constitution (2000)

Jed Handelsman Shugerman, “Marbury and Judicial Deference: The Shadow of Whittington v. Polk and Maryland Judiciary Battle,” 5 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 58 (2002), https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/jcl/vol5/iss1/3/

William W. Van Alstyne, “A Critical Guide to Marbury v. Madison, 18 Duke L. J. 1-47 (1969), https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/faculty_scholarship/544/

Louise Weinberg, “Marbury v. Madison: A Bicentennial Symposium,” 89 Va. L. Rev. 1235 (2003), https://law.utexas.edu/faculty/uploads/publication_files/ourmarburypub.pdf

Nicholas Mosvick is a Senior Fellow for Constitutional Content at the National Constitution Center.