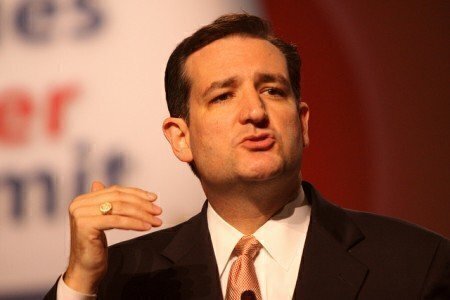

An updated Congressional Research Service report is adding some new background on the controversy over U.S. presidential candidates like Ted Cruz who were born overseas and who are seeking office.

While not mentioning Cruz directly, the analysis prepared for Congress recaps legal “birther cases” since 2011, and at least in one paragraph, legislative attorney Jack Maskell states that it is unclear that a situation like Cruz’s has been settled definitively.

The report was published on January 11, 2016 by the CRS and written by Maskell. Such reports are not made directly available to the public, but they do appear on paid services and eventually on websites run by interested groups. The January 11 report appeared on a blog, and Constitution Daily has confirmed the update on computer networks accessible by Congress and its staff.

Cruz was born in 1970 in Calgary, Alberta, Canada to a U.S. citizen mother and a Cuban father. Critics such as Donald Trump want Cruz to prove in court that his birth situation doesn’t conflict with Article I of the Constitution, which reads, “No person except a natural born citizen, or a citizen of the United States, at the time of the adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President.”

The 50-page brief is mostly the same as the CRS’s 2011 report, which is frequently cited in the debate over Cruz’s eligibility to run for President. In one section, “Legal Cases and Birth Outside of the United States,” the report repeats a statement from 2011.

“Under the Constitution, only 'natural born' citizens are eligible to become President or Vice President of the United States. The Constitution nowhere defines this term, and its precise meaning is still uncertain. It is clear enough that native-born citizens are eligible and that naturalized citizens are not. The doubts relate to those who acquire U.S. citizenship by descent, at birth abroad to U.S. citizens,” it says, adding italics in the paragraph for emphasis.

It continues, “The uncertainty concerning the meaning of the natural-born qualification in the Constitution has provoked discussion from time to time, particularly when the possible presidential candidacy of citizens born abroad was under consideration. There has never been any authoritative adjudication. It is possible that none may ever develop,” it says. “However, there is substantial basis for concluding that the constitutional reference to a natural-born citizen includes every person who was born a citizen, including native-born citizens and citizens by descent.” (Again, the italics were added here for emphasis by the CRS.)

Then there is a new update to make it clear that there is a debate about the ability of a foreign-born candidate like Cruz to run for President, based on at least two older court cases. (The CRS report doesn’t cite Cruz by name in this passage.)

“The existence of these earlier cases, including the Supreme Court’s characterization in Wong Kim Ark of statutory citizenship of those born abroad, raise interesting contentions and considerations that have not necessarily been definitively resolved with regard to the ‘natural born’ citizenship status ̶ for purposes of presidential eligibility — of those who have obtained U.S. citizenship by virtue of being born abroad to a U.S. citizen parent or parents,” it says.

The Supreme Court’s Wong Kim Ark decision in 1898 found that a child born in the United States to foreign citizens was a United States citizen under the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause.

The report, as in 2011, describes the differences between people who believe in a narrow interpretation of the “natural born citizen” clause (which would bar Cruz from running) and those that believe in a broad interpretation (which would allow Cruz to run).

In the narrow interpretation, natural-born citizens need to be born on American soil or under American jurisdiction. The theory states that other citizens are “naturalized” by laws, including all children born to American parents overseas. Under Article I, a naturalized citizen couldn’t run for President, for example, under this theory, because the act of "naturalization" happens automatically at birth outside of the United States.

These critics cite a passage in the Wong Kim Ark decision referenced in the 2016 CRS report, written for the majority in 1898 by Justice Horace Gray, that reads:

“Every person born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, becomes at once a citizen of the United States, and needs no naturalization. A person born out of the jurisdiction of the United States can only become a citizen by being naturalized, either by treaty, as in the case of annexation of foreign territory, or by authority of Congress, exercised either by declaring certain classes of persons to be citizens, as in the enactments conferring citizenship upon foreign-born children of citizens, or by enabling foreigners individually to become citizens by proceedings in the judicial tribunals, as in the ordinary provisions of the naturalization acts.” (Again, the italics above were added by the CRS in the 2016 report.)

The report also discusses the “substantial basis” for the broader interpretation of the natural born citizen clause, which looks to the authority of Congress to pass laws to define the conditions placed on citizenship. Under that interpretation, Cruz is eligible to run for President.

It notes that citizenship status has been changed by statute in England for more than 600 years, an important reference in regard to how the Founders may have intended for Congress to deal with the issue. “It would not be inconsistent nor necessarily unintended that such status might be affected by legislation by Congress (i.e., ‘except as modified by statute’), as it had been in England by Parliament.”

The report also points to some recent Supreme Court decisions that support this argument. In the 2001 Tuan Anh Nguyen v. INS case, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that earlier cases recognized the “wide deference afforded to Congress in exercising its immigration and naturalization power.” Under the current citizenship law, a child born to a U.S. citizen mother becomes a citizen automatically, regardless of where its birth takes place.

“First, a citizen mother expecting a child and living abroad has the right to reenter the United States so the child can be born here and be a 14th Amendment citizen. From one perspective, then, the statute simply ensures equivalence between two expectant mothers who are citizens abroad if one chooses to reenter for the child's birth and the other chooses not to return, or does not have the means to do so,” wrote Kennedy.

In a more recent decision, Zivotofsky v. Kerry (2105), Justice Clarence Thomas said that ““[Congress] has determined that children born abroad to U.S. parents, subject to some exceptions, are natural-born citizens who do not need to go through the naturalization process.”

The report concludes that, “the weight of more recent federal cases, as well as the majority of scholarship on the subject, also indicate that the term ‘natural born citizen’ would most likely include, as well as those native born citizens born in the U.S., those born abroad to U.S. citizen-parents, at least one of whom had previously resided in the United States, or those born abroad to one U.S. citizen parent who, prior to the birth, had met the requirements of federal law for physical presence in the country.”

Whether these legal arguments about Cruz’s eligibility ever get decided by a court remains to be seen. Similar challenges made against John McCain (who was born in Panama) and Barack Obama failed for a lack of standing to sue in court. And then there is a broader issue of the plaintiffs asking a court to decide a political question - something courts usually shun.

For now, parts of the debate will focus on the fact that U.S. laws until 1934 only allowed children born to U.S. fathers overseas to automatically claim American citizenship, and there will be added scrutiny about how the Founders viewed the national born citizen clause.

Bryan A. Garner, a lawyer, author and the editor of Black’s Law Dictionary, went into great detail last week in an article for The Atlantic about the history of such controversies going back to 1352. His conclusion was that "all in all, it seems highly likely that the Supreme Court would today hold that the foreign-born child of a mother-citizen is eligible for the Presidency under Article II of the Constitution."

A key would be how the Court viewed the case in light of the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause, and a discriminatory difference that restricted citizenship to children, born outside the U.S., to only a father as a U.S. citizen. "Judged by current standards of equal protection, no such discriminatory difference would be upheld by the Supreme Court today. But an originalist interpretation would almost certainly be to the contrary," Garner said.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.