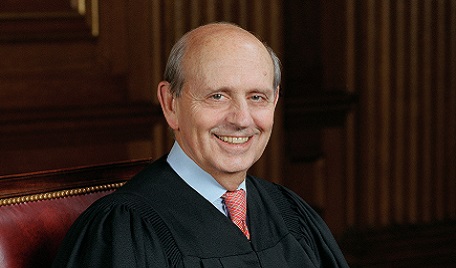

During U.S. Supreme Court arguments in April in the case of the cursing cheerleader, Justice Stephen Breyer was frustrated with the lawyers for the cheerleader and the school district that had suspended her for her vulgar comments on social media.

One side wanted the court to rule that a 1969 decision that said schools may regulate students’ on-campus speech that materially and substantially disrupts class work and discipline of the school applies to their off-campus speech. The other side fought for broad student-speech protection.

One side wanted the court to rule that a 1969 decision that said schools may regulate students’ on-campus speech that materially and substantially disrupts class work and discipline of the school applies to their off-campus speech. The other side fought for broad student-speech protection.

“There are dozens of areas that didn’t used to be thought of as within the purview of the public school,” Breyer said, noting schools feed hungry children, care for them when they can’t send them home because no one is there and more.

Add to that the Internet, where students communicate with each other regularly, research, do their homework, he said.

“How do I get a standard out of that? I’m frightened to death of writing a standard,” Breyer told them.

Breyer probably didn’t know until several days later or longer, after the justices sat down to take an initial vote in the case, that Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. would assign the majority opinion to him. The result was pure Stephen Breyer.

Breyer has never been a fan of so-called bright-line rules or tests. Law and the issues that come before the court are more complex and often require more nuanced responses. The cheerleader’s case was one of them.

Breyer began his opinion by laying out what the court has said about student speech. In that 1969 decision, the court ruled that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression” even “at the school house gate.” But courts have to apply the First Amendment in light of the special characteristics of the school environment. One characteristic, the justices have said, is that schools sometimes stand in place of parents.

So what types of speech had the court previously said schools may regulate? Indecent, lewd or vulgar speech during a school assembly; speech uttered on a class trip promoting illegal drug use, and speech that others may believe bears the approval of the school, such as what appears in a school-sponsored newspaper.

“We do not believe the special characteristics that give schools additional license to regulate student speech always disappear when a school regulates speech that takes place off campus,” Breyer wrote.

He gave examples of off-campus behavior that schools might regulate such as severe bullying or harassment of certain persons; threats to teachers and breaches of school security devices, among others. Even B.L., the cheerleader in the case before them, he said, acknowledged times when schools could regulate off-campus speech, he said.

“Particularly given the advent of computer-based learning, we hesitate to determine precisely which of many school-related off-campus activities belong on such a list,” Breyer wrote. “Neither do we now know how such a list might vary, depending upon a student’s age, the nature of the school’s off-campus activity, or the impact upon the school itself.”

Based on that uncertainty, Breyer said the court would not give a “broad, general First Amendment rule” that states what counts as off-campus speech and whether the First Amendment must give way to a school’s need to prevent a substantial disruption of the school environment.

But if there was to be no rule, what could the court offer to guide schools or students in the First Amendment arena? Breyer said the court could do two things. It could give three features of off-campus speech that should give schools pause before regulating that speech, and it could offer the cheerleader’s speech as an example.

The three features that diminish a school’s interest in regulating off-campus speech, in a nutshell, are: off-campus speech normally falling within the zone of parental, not school-related, responsibility; school efforts regulating off-campus speech coupled with on-campus speech that may control all speech a student utters in 24 hours; and the fact that schools, which are “nurseries of democracy,” have an interest in protecting a student’s unpopular speech.

“We leave for future cases to decide where, when, and how these features mean the speaker’s off-campus location will make the critical difference,” Breyer wrote.

But there still was the matter of the cheerleader’s vulgar expression on Snapchat. She and her friend, with middle fingers raised, wrote “F… school f… softball f… cheer f… everything.”

Breyer wrote that her words did not fall outside of the First Amendment’s protection. Although crude, they were not “fighting words” and were not “obscene.” Her speech took place after school hours at a location beyond the school and did not identify the school or target anyone.

Breyer also examined the school district’s arguments that it had interests justifying its discipline of the cheerleader, such as teaching good manners, preventing disruption in the classroom, and a concern for morale. But he said the school offered little evidence to support those interests in B.L.’s circumstances.

“It might be tempting to dismiss B. L.’s words as unworthy of the robust First Amendment protections discussed herein. But sometimes it is necessary to protect the superfluous in order to preserve the necessary,” Breyer wrote.

Justice Samuel Alito Jr., joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch, wrote a separate opinion, elaborating on the framework set up the court’s opinion. He noted that with 90,000 public school principals, there would be occasions when some will “get carried away” as happened in B. L.’s case.

If the court’s decision teaches any lesson, he wrote, it is that “school officials should proceed cautiously before venturing into this territory.”

The lone dissenter, Justice Clarence Thomas said the court overlooked 150 years of history—and how ordinary citizens viewed the scope of free speech rights at the time of the 14th Amendment’s ratification – that supported the cheerleading coach’s authority to suspend B.L.

Despite not offering courts and school officials a bright test or clear guidance that fits all off-campus speech situations, the court’s decision drew little criticism and appeared to satisfy free speech advocates and schools alike. That is the best evidence that Breyer, and the court, struck the right balance, at least for now.

Marcia Coyle is a regular contributor to Constitution Daily and the Chief Washington Correspondent for The National Law Journal, covering the Supreme Court for more than 20 years.