The sons of legendary athlete Jim Thorpe want the Supreme Court to help get their father’s remains returned to Oklahoma in a dispute over absurdity and museums.

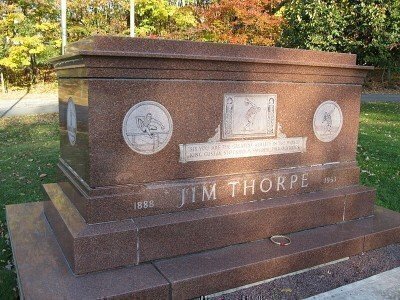

The Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma, Richard Thorpe and William Thorpe claim that the northeastern Pennsylvania town where Jim Thorpe’s body resides in an above-ground mausoleum should be treated as a museum, and subject to federal law under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (or NAGPRA).

The Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma, Richard Thorpe and William Thorpe claim that the northeastern Pennsylvania town where Jim Thorpe’s body resides in an above-ground mausoleum should be treated as a museum, and subject to federal law under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (or NAGPRA).

Their petition to the Supreme Court in Sac and Fox Nation v. Borough of Jim Thorpe was co-written by noted constitutional lawyer Jeffrey L. Fisher from Stanford Law School, who won a major Supreme Court case in 2014 about the warrantless searches of cell phones.

The current legal fight started with a decision in 1953 by Thorpe’s late third wife, Patricia, to sell his remains just after his death to two towns in eastern Pennsylvania called Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk.

Patricia Thorpe claimed the body the night before a traditional Sac and Fox burial ceremony could take place in Oklahoma. Thorpe’s remains were sold on the condition that the towns combine, call themselves “Jim Thorpe,” and erect a monument to Thorpe that included his remains.

The Thorpes and the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma want Thorpe’s body be returned to Oklahoma under terms of NAGPA.

The plaintiffs claimed the Thorpe memorial falls under NAGPRA's definition of a museum receiving federal funds and his remains are, in fact, artifacts that should be returned to his lineal descendants in Oklahoma.

In October 2014, the Third U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Thorpe's body should remain in the borough, calling a U.S. District Judge’s prior ruling in the case “absurd” in a legal sense. (The absurdity doctrine in legal cases is when a strict interpretation of a law would lead to absurd results contrary to the lawmakers’ intent.)

Fisher and his team are questioning just how “absurd” the appeals court ruling was in this case in applying the absurdity doctrine.

“This case does not warrant invocation of the absurdity doctrine. Applying NAGPRA to entities that acquired remains from a relative of the deceased does not thwart Congress’s purposes. Rather, it is The Third Circuit’s decision that thwarts Congress’s goal of giving Native Americans control over their people’s remains,” the attorneys argue.

U.S. District Judge Richard Caputo had earlier determined that Thorpe’s body should be sent back to Oklahoma because Jim Thorpe Borough met NAGPRA’s definition of a museum because it received federal funds.

But the appeals court disagreed. "Thorpe's remains are located in their final resting place and have not been disturbed," Chief Judge Theodore McKee said in his October ruling. "We find that applying (the repatriation law) to Thorpe's burial in the borough is such a clearly absurd result and so contrary to Congress's intent to protect Native American burial sites that the borough cannot be held to the requirements imposed on a museum under these circumstances."

Link: Read McKee’s ruling

"NAGPRA was intended as a shield against further injustices to Native Americans," McKee said. "It was not intended to be wielded as a sword to settle familial disputes within Native American families."

Thorpe stunned the world by winning the pentathlon and decathlon in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics by a huge margin over two favorites. The news made global headlines, and Thorpe received a hero's welcome in New York City.

Little known outside the United States, Thorpe was a college football star at Carlisle Institute in central Pennsylvania and was already a legend there by 1911 after he scored all his team’s points in a win over Harvard.

Thorpe’s parents were both part-Native American at a time when some Native Americans didn’t have the right to vote in elections. In fact, until a congressional act in 1924, about one-third of Native Americans living in the United States weren’t considered citizens and were not eligible to vote.

Thorpe grew up in the Sac and Fox Nation in what became Oklahoma. He had a multicultural background, since his parents were Catholic and Native American. Thorpe fell on tough financial times after his sports career ended, and he died in California in 1953 at the age of 64, just two years after his story was made into a movie starring Burt Lancaster.