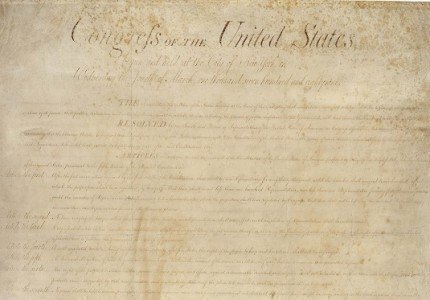

In this essay from the National Constitution Center's Interactive Constitution project, John Inazu from the Washington University in St. Louis and Burt Neuborne from the New York University School of Law explain how the First Amendment protects two distinct rights: assembly and petition.

The “right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances” protects two distinct rights: assembly and petition. The Clause’s reference to a singular “right” has led some courts and scholars to assume that it protects only the right to assemble in order to petition the government. But the comma after the word “assemble” is residual from earlier drafts that made clearer the Founders’ intention to protect two separate rights. For example, debates in the House of Representatives during the adoption of the Bill of Rights linked “assembly” to the arrest and trial of William Penn for participating in collective religious worship that had nothing to do with petitioning the government.

The “right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances” protects two distinct rights: assembly and petition. The Clause’s reference to a singular “right” has led some courts and scholars to assume that it protects only the right to assemble in order to petition the government. But the comma after the word “assemble” is residual from earlier drafts that made clearer the Founders’ intention to protect two separate rights. For example, debates in the House of Representatives during the adoption of the Bill of Rights linked “assembly” to the arrest and trial of William Penn for participating in collective religious worship that had nothing to do with petitioning the government.

While neither “assembly” nor “petition” is synonymous with “speech,” the modern Supreme Court treats both as subsumed within an expansive “speech” right, often called “freedom of expression.” Many scholars believe that focusing singularly on an expansive idea of speech undervalues the importance of providing independent protection to the remaining textual First Amendment rights, including assembly and petition, which are designed to serve distinctive ends.

Assembly

Assembly is the only right in the First Amendment that requires more than a lone individual for its exercise. One can speak alone; one cannot assemble alone. Moreover, while some assemblies occur spontaneously, most do not. For this reason, the assembly right extends to preparatory activity leading up to the physical act of assembling, protections later recognized by the Supreme Court as a distinct “right of association,” which does not appear in the text of the First Amendment.

The right of assembly often involves non-verbal communication (including the message conveyed by the very existence of the group). A demonstration, picket-line, or parade conveys more than the words on a placard or the chants of the crowd. Assembly is, moreover, truly “free,” since it allows individuals to engage in mass communication powered solely by “sweat equity.”

The right to assemble has been a crucial legal and cultural protection for dissenting and unorthodox groups. The Democratic-Republican Societies, suffragists, abolitionists, religious organizations, labor activists, and civil rights groups have all invoked the right to assemble in protest against prevailing norms. When the Supreme Court extended the right of assembly beyond the federal government to the states in its unanimous 1937 decision, De Jonge v. Oregon, it recognized that “the right of peaceable assembly is a right cognate to those of free speech and free press and is equally fundamental.”

The right of assembly gained particular prominence in tributes to the Bill of Rights as the United States entered the Second World War. Eminent twentieth-century Americans, including Dorothy Thompson, Zechariah Chafee, Louis Brandeis, John Dewey, Orson Welles, and Eleanor Roosevelt, all emphasized the significance of the assembly right. At a time when civil liberties were at the forefront of public consciousness, assembly figured prominently as one of the original “Four Freedoms” (along with speech, press, and religion). When, however, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt switched to a different grouping of “four freedoms” in an effort to rally support for American entry into WWII, assembly (and press) dropped out. Neglect of assembly as a freestanding right has continued ever since. In fact, the Supreme Court has not decided a case explicitly on free assembly grounds in over thirty years. But despite its recent state of hibernation, the freedom to assemble peaceably remains integral to what Justice Robert Jackson once called “the right to differ.”

Petition

The right to “petition the Government for redress of grievances” is among the oldest in our legal heritage, dating back 800 years to the Magna Carta, and receiving explicit protection in the English Bill of Rights of 1689, long before the American Revolution. Ironically, the modern Supreme Court has all but read the venerable right to petition out of the Bill of Rights, effectively holding that it has been rendered obsolete by an expanding Free Speech Clause. As with assembly, however, the right to petition is not simply an afterthought to the Free Speech Clause.

The right to petition plays an important role in American history. The Declaration of Independence justified the American Revolution by noting that King George III had repeatedly ignored petitions for redress of the colonists’ grievances. Legislatures in the Revolutionary period and long into the nineteenth century deemed themselves duty-bound to consider and respond to petitions, which could be filed not only by eligible voters but also by women, slaves, and aliens. John Quincy Adams, after being defeated for a second term as President, was elected to the House of Representatives where he provoked a near riot on the House floor by presenting petitions from slaves seeking their freedom. The House leadership responded by imposing a “gag rule” limiting petitions, which was repudiated as unconstitutional by the House in 1844.

One of the risks of representative democracy is that elected officials may favor the narrow partisan interests of their most powerful supporters, or choose to advance their own personal interests instead of viewing themselves as faithful agents of their constituents. A robust right to petition is designed to minimize such risks. By being forced to acknowledge and respond to petitions from ordinary persons, officials become better informed and must openly defend their positions, enabling voters to pass a more informed judgment.

The right to petition should be contrasted with the right to instruct. A right of instruction permits a majority of constituents to direct a legislator to vote a particular way, while a right of petition assures merely that government officials must receive arguments from members of the public. The drafters of the Bill of Rights decided not to include a right of instruction in order to encourage legislators to exercise their best judgment about how to vote.

Today, in Congress and in virtually all 50 state legislatures, the right to petition has been reduced to a formality, with petitions routinely entered on the public record absent any obligation to debate the matters raised, or to respond to the petitioners. In a political system where incumbent legislators can make it all but impossible to mount a credible re-election challenge, an energized right to petition might link modern legislators more closely to the entire electorate they are pledged to serve. Some scholars have even argued that the Petition Clause includes an implied duty to acknowledge, debate, or even vote on issues raised by a petition. The precise role of a robust Petition Clause in our twenty-first century democracy cannot be explored, however, until the Supreme Court frees the Clause from its current subservience to the Free Speech Clause.

John Inazu is Sally D. Danforth Distinguished Professor of Law & Religion and Professor of Political Science at the Washington University In St. Louis School of Law. Burt Neuborne is Norman Dorsen Professor of Civil Liberties and founding Legal Director of the Brennan Center for Justice, New York University School of Law.

To read more from these authors on Matters of Debate about this topic, go to our Interactive Constitution First Amendment section at https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/amendments/amendment-i