Unlike other recent campaigns, the specter of a tied election is less likely to hang over the 2024 presidential election due to changes related to the 2020 decennial United States Census.

The Constitution uses the 10-year Census to determine the number of representatives in the House for the next decade. The number of electors in the Electoral College is equivalent to the number of members in the House of Representatives (435) and members of the Senate (100), with three additional electors from the District of Columbia, thanks to the 23rd Amendment. All told, there are 538 electors, and a presidential candidate needs at least 270 electoral votes to win outright.

However, the changes in several battleground states since 2020 have made the math challenging for a race that ends with the two 2024 candidates, Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump, each getting 269 electoral votes.

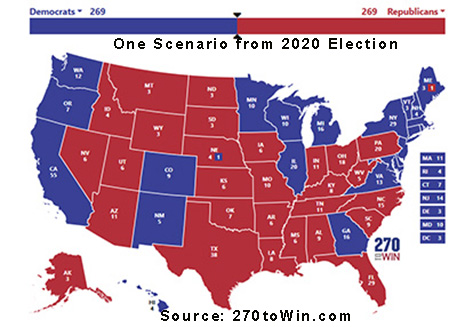

Back in 2020, several realistic scenarios existed for a tied election. According to the website 270 to Win, if Georgia, Arizona, and Wisconsin had gone to the Republican candidate, the results would have shown 269 electoral votes for Trump and also 269 votes for his opponent, former Vice President Joe Biden. In a similar 2020 scenario, wins for Trump in Pennsylvania, Arizona, and Nevada would have left the results at 269 electoral votes for each candidate. In short, any combination of 37 electoral votes in 2020 moving from the Biden column to the Trump column would have left the results tied.

Back in 2020, several realistic scenarios existed for a tied election. According to the website 270 to Win, if Georgia, Arizona, and Wisconsin had gone to the Republican candidate, the results would have shown 269 electoral votes for Trump and also 269 votes for his opponent, former Vice President Joe Biden. In a similar 2020 scenario, wins for Trump in Pennsylvania, Arizona, and Nevada would have left the results at 269 electoral votes for each candidate. In short, any combination of 37 electoral votes in 2020 moving from the Biden column to the Trump column would have left the results tied.

The 2020 Census changed the representation for the 2024 election in several states. Colorado, Florida, and North Carolina each gained a vote in the Electoral College, while Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania each lost one seat. Texas gained two votes. Of the seven consensus swing states (Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin), their combined number of electoral votes fell from 94 votes in 2020 to 93 votes in 2024, greatly lessening any combination of states creating a tied vote in the 2024 election. States not considered as contested states, such as Ohio, need to be in play to make a tied election more likely in 2024.

However, two states, Maine and Nebraska, split their electoral votes by district. Nebraska’s 2nd congressional district has been the subject of much attention, since it went for the Democrats in 2020, in a state that is solidly Republican. In one scenario in 2024, if Harris, the Democratic candidate, takes three key swing states (Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin) in 2024 and Trump captures the other four states, Harris would have 270 election votes, one more than needed to win. The loss of the 2nd congressional district to the Republicans would result in a tied contest.

Since the Constitution was ratified in June 1788, only one presidential contest has ended in a tied election. Under the Constitution’s original presidential election system, the Electoral College, in conjunction with Congress, would choose the winners of the presidential election.

Under Article 1, Section 1, the state legislatures would select electors to cast votes sent to Congress to certify. Some states used popular voting to pick electors, while others turned to state legislatures to choose electors. Each elector voted for two candidates. The person with the most votes certified by Congress became president. The second-place candidate was vice president.

The original presidential election system broke down in 1800, when Thomas Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr, tied for first place, but they did not have a majority of the electoral college votes. The tie moved the election to the House of Representatives to decide. In the end, Jefferson became president and Burr, his rival, was vice president.

In response, Congress proposed the 12th Amendment, which was ratified before the 1804 election. The amendment made clear that electors had to cast separate votes for the president and the vice president. If a candidate did not get a majority of electoral votes after the results were certified in Congress, the House would choose the new president, and the Senate would elect a new vice president.

The 12th Amendment did not eliminate the chances of a tied presidential election, but it made the process of picking a winner in Congress a much cleaner one.

Since 1804, Congress had decided two elections where no candidate had the majority of electoral votes: the 1824 presidential election and the 1836 vice-presidential election. In the 1824 election, Andrew Jackson had the most popular votes, but not the majority (he had won 99 electoral votes which was 32 fewer than he needed to win the presidency—the other candidates John Quincy Adams won 84 electoral votes, William H. Crawford won 41 and Henry Clay won 37). The House chose Adams in the contingent election instead of Jackson. In the 1836 election, Virginia shunned Martin Van Buren’s running mate, Richard Mentor Johnson, giving its votes to another vice presidential candidate in a case of unfaithful electors rejecting an elected candidate. The Senate, however, voted for Johnson in the run-off election.

The 23rd Amendment’s ratification in 1961 increased the chance of a tied election as a simple matter of mathematics. Before 1961, the total number of electors in the presidential election had been an odd number since 1904. The addition of electoral votes for the District of Columbia because of the 23rd Amendment made the electoral college total an equally divisible number: 538 electors. In the modern major two-party system, a dead-heat 269-269 Electoral College vote was now possible, assuming all electoral votes were cast and then certified by Congress.

Today, if the presidential election remains tied after expected legal challenges and the submission of certified results from the states to Congress, the newly elected House would decide the presidential winner in January 2025 based on a vote of state delegations and not individual representatives. Currently, the Republicans control 26 of the 50 House delegations that would vote in a contingent election for president. The Senate would vote to pick the vice president based on a majority of members casting votes.

Scott Bomboy is editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.