As the battle over the Trump administration’s use of National Guard troops to protect immigration enforcement officials plays out in the legal system, some formerly obscure acts of Congress could play a key role in the appeals process.

On Thursday night, Judge April M. Perry of the United States District Court of the Northern District of Illinois issued a temporary restraining order against the deployment of troops in Illinois. Perry had heard arguments during the day in a lawsuit asking the court to bar the National Guard from Chicago, in part citing violations of the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878.

On Thursday night, Judge April M. Perry of the United States District Court of the Northern District of Illinois issued a temporary restraining order against the deployment of troops in Illinois. Perry had heard arguments during the day in a lawsuit asking the court to bar the National Guard from Chicago, in part citing violations of the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878.

Also, in public statements, President Donald Trump has stated he might invoke the Insurrection Act of 1807 to use military forces such as the National Guard in a limited fashion in domestic circumstances.

The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit also heard arguments on Thursday over whether the administration has the ability to deploy Oregon National Guard troops. In court papers, government attorneys argued that the president has the power under 10 U.S.C. § 12406, to federalize the National Guard.

A Tale of Two Acts and Two Statutes

The Posse Comitatus Act dates back to when federal troops left formerly rebellious states as part of the pact that ended a key phase of the Reconstruction in the1870s. The act was originally intended to make it difficult for federal forces to execute criminal laws in those southern states, as they had between 1865 and 1878.

In the period after the Civil War, federal troops in the former states of the Confederacy had been used to enforce laws. The ex-Confederate states strongly opposed this policy. As explained in a 2018 report from the Congressional Research Service, the Posse Comitatus Act outlawed the willful use of any part of the Army or Air Force as a “posse comitatus” to execute the law unless expressly authorized by the Constitution or an act of Congress.

Violations of the Posse Comitatus Act occur when federal forces take over tasks assigned to a civil government, or when federal armed forces perform tasks solely for purposes of civilian government. Also, civilian law enforcement is barred from “direct active use” of military investigators, and the use of the military cannot “pervade the activities of the civilian officials.”

According to the CRS, clear exceptions to the Posse Comitatus Act exist where “Congress has delegated authority to the president to call forth the military during an insurrection or civil disturbance.”

Another statute, Section 502 of Title 32, U.S. Code, permits the use of the National Guard if it takes part in “homeland defense activity” that is “undertaken for the military protection of the territory or domestic population of the United States, or of infrastructure or other assets of the United States determined by the Secretary of Defense as being critical to national security, from a threat or aggression against the United States.”

The statute cited in the Oregon case, 10 U.S.C. § 12406, was used by the administration to justify the use of National Guard troops in California. It allows the president to federalize the National Guard if the United States is invaded or is in danger of invasion by a foreign nation; there is a rebellion or danger of a rebellion against the authority of the government of the United States; or the president is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States.

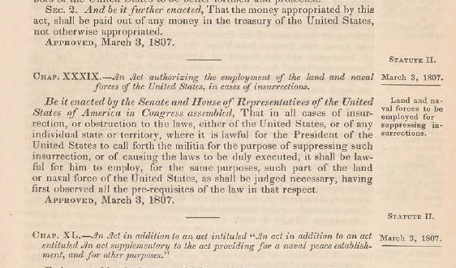

The Insurrection Act of 1807 is one of a series of laws that Congress has passed to allow the president to deploy the National Guard or federal armed forces to deal with “unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States.”

The last use of the Insurrection Act was in May 1992, when President George H.W. Bush directed the use of 3,500 federal troops after California’s governor requested help when the National Guard could not contain riots related to the Rodney King case. In 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent federal soldiers under another statute to enforce the desegregation at Central High School in Little Rock, Ark.

The Militia Clauses

The founders had firsthand experience with the need to contain public disturbances in limited circumstances. The Articles of Confederation, which preceded the Constitution, lacked the power to initially deal with Shays’ Rebellion in 1786. At the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, the delegates sought to balance the need for stronger militias and a federal military force, with their fear of a standing army that might abuse its powers.

The Constitution gave overlapping powers to civilians to oversee military forces. Article I, Section 8, called for Congress “to provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions” and “To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the States respectively.” Article II, Section 2, established that the “President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.”

The Constitution’s Article IV, Section 4, also made it clear that the federal government had a responsibility to protect states against “Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or of the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened) against domestic Violence.”

After the Constitution was ratified, Congress granted the president additional powers under the Militia Act of 1792 to temporarily “call forth such number of the militia of the state or states” at the request of state leaders. The Militia Act of 1795 gave the president more powers to call out the militia by eliminating time limits for their use in the field and removing the required consent of a federal judge before taking action to call out troops.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center. This article includes prior work by the author from two previous blog posts.