Before leaving the White House, President Joe Biden granted several pardons to people who may be asked to testify in the future before Congress. But do those pardons, if accepted, remove the recipients’ rights to “take the Fifth” if subpoenaed during a federal investigation?

On Jan. 20, 2025, Biden issued a series of pardons to the January 6 investigating committee, Dr. Anthony Fauci, Liz Cheney and other people who have been criticized by supporters of President Donald Trump. Questions quickly arose about the impact of the pardons on the ability of recipients to refuse to testify, answer questions, or provide documents before a Congressional investigating committee. The same question came up in 2017 when then-President Trump was considering pardons for some former associates.

On Jan. 20, 2025, Biden issued a series of pardons to the January 6 investigating committee, Dr. Anthony Fauci, Liz Cheney and other people who have been criticized by supporters of President Donald Trump. Questions quickly arose about the impact of the pardons on the ability of recipients to refuse to testify, answer questions, or provide documents before a Congressional investigating committee. The same question came up in 2017 when then-President Trump was considering pardons for some former associates.

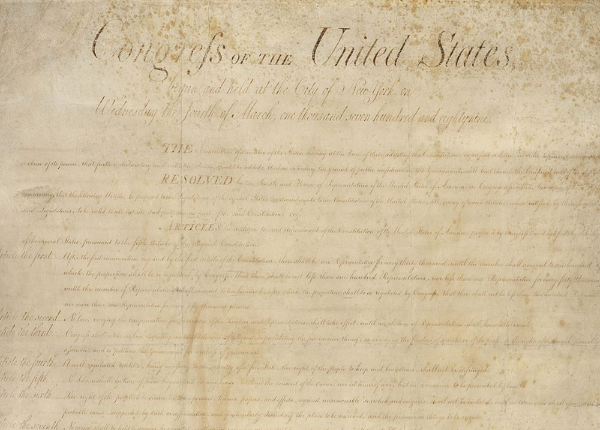

In play here are two critical parts of the Constitution: the Fifth Amendment’s Self-Incrimination Clause and the president’s power to issue pardons under Article II. When considered together, these provisions raise questions about the ability of a person accepting a pardon to invoke the Fifth Amendment before Congress.

The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution guarantees that no person “shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” This constitutional protection can be used in a variety of circumstances when an individual is under investigation by authorities or asked to testify.

According to the Constitution Annotated from the Library of Congress, the Supreme Court confirmed in several decisions from 1955 that witnesses in congressional investigations can invoke the protections of the Self-Incrimination Clause: “Although the [Fifth] Amendment’s protection expressly refers to criminal cases[s], the Court has nevertheless found the privilege against self-incrimination to be available to a witness appearing before a congressional committee,” the LOC says. “Once properly invoked, the privilege protects a witness from being compelled to provide Congress with statements that may directly or indirectly furnish evidence which could be used against the witness in a subsequent criminal prosecution or from being punished for their refusal to respond to committee inquiries.”

The president has pardon or clemency power under Article II, Section 2, Clause 1, of the Constitution, under the Pardon Clause. The clause says the president “shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” While the president’s powers to pardon seem unlimited, a presidential pardon can only be issued for a federal crime, and pardons can’t be issued for impeachment cases tried and convicted by Congress.

In 2017, retired ambassador Keith Harper in the blog Just Security explained the conflict between the Fifth Amendment’s Self-Incrimination Clause and the president’s pardon powers. “Most likely [President Trump] has been informed of one important fact about his pardon power, anyone he pardons is no longer under criminal jeopardy for federal crimes and, accordingly, Fifth Amendment protection for self-incrimination evaporates,” Harper said.

This precedent dates back to 1896 and the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Walker. In his majority opinion, Justice Henry Billings Brown found that if a “witness has already received a pardon, he cannot longer set up his [Fifth Amendment] privilege, since he stands, with respect to such offense, as if it had never been committed.” Brown cited cases dating back to English law and the Aaron Burr treason trial as supporting that conclusion.

A second Court decision, Burdick v. United States (1915), added another dimension to the question. George Burdick, a newspaper editor, published an article alleging misconduct at a customs house. Burdick asserted this Fifth Amendment rights in front of a grand jury, which was investigating a leak of information from the Treasury Department to the newspaper.

President Woodrow Wilson granted a full pardon to Burdick, even though Burdick was not charged with a crime. Wilson’s pardon may have been in an effort to compel Burdick to testify since Burdick could not “take the Fifth” if he received a pardon under the Brown precedent. Instead, Burdick refused to accept Wilson’s pardon, and then he was held in contempt when questioned again by Congress and cited the Fifth Amendment.

Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice Joseph McKenna said that “a witness may refuse to testify on the ground that his testimony may have an incriminating effect, notwithstanding the President offers, and he refuses, a pardon for any offense connected with the matters in regard to which he is asked to testify.” McKenna cited a precedent from United States v. Wilson (1833), when Chief Justice John Marshall found such a pardon may be “rejected by the person to whom it is tendered; and if it be rejected, we have discovered no power in a court to force it on him.”

In December 2020, Aziz Huq from the University of Chicago wrote in a Washington Post opinion piece that “pardoned people are by definition no longer in legal jeopardy for federal offenses, so they can no longer claim any Fifth Amendment privilege in that realm,” with Huq citing the Brown decision from 1896. “If they refuse to speak, the legislature can flex its contempt power: At one extreme, this can involve the threat of jail time, but it can also mean daily fines calibrated to the asserted wealth of a reluctant witness.”

However, the Fifth Amendment claim against self-incrimination might still be relevant if someone is asked to testify before Congress about activities that could violate state laws. In 2017, Harper cited one example in his Just Security blog post. “Money laundering, for example, is illegal both under federal law and New York state law. . . . And in such fairly circumscribed cases, the pardoned individual would still enjoy Fifth Amendment protection in discussing facts of relevance to those cases.”

Eugene Volokh, of the UCLA School of Law and the Hoover Institution, offered a more detailed answer in a December 2024 post on his Volokh Conspiracy blog. In a discussion about Hunter Biden’s pardon, Volokh cites Brown as possibly eliminating Biden’s Fifth Amendment protections in congressional testimony with a caveat. “The privilege disappears only when there’s no realistic prospect of prosecution by any American government, federal or state. So, if a witness is asked about something, and the answer might lead to state prosecution for which the state statute of limitations hasn’t run, the witness can refuse to testify because of that risk of state prosecution, even if a federal prosecution is taken off the table by the federal pardon.”

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.