Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center's constitutional literacy adviser, looks at the latest claims that the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court violates the Constitution in some of its actions, and the challenges those claims would face in court.

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

“Dramatic shifts in technology and law have changed the role of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court since its creation in 1978 – from reviewing government applications to collect communications in specific cases, to issuing blanket approvals of sweeping data collection programs affecting millions of Americans. These fundamental changes not only erode Americans’ civil liberties, but likely violate Article III of the U.S. Constitution, which limits courts to deciding concrete disputes between parties rather than issuing opinions on abstract questions….Today’s FISA Court does not operate like a court at all, but more like an arm of the intelligence establishment….The FISA Court’s wholesale approval process also fails to satisfy standards set forth in the Fourth Amendment, which protect against warrantless searches and seizures.”

– Statements by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, announcing on March 18 the release of a new report, “What Went Wrong With the FISA Court.” The full report is available at www.brennancenter.org

“It is neither desirable nor is it remotely likely that civil liberty will occupy as favored a position in wartime as it does in peacetime. But it is both desirable and likely that more careful attention will be paid by the courts to the basis for the government’s claims of necessity as a basis for curtailing civil liberty. The laws will thus not be silent in time of war, but they will speak with a somewhat different voice.”

– Excerpt from the book by the late Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, published in 1998, “All the Laws But One: Civil Liberties in Wartime.”

WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

Americans, in modern times as in the early days of the Republic, have not settled the constitutional question of when America is actually at war, or even what steps must be taken for it to go into armed conflict. Of course, the Constitution assigns to Congress the power to declare war, and to the President the authority to direct the military in wartime operations. But it is a truism in modern times that war – or at least the global threat of violent conflict – seems perpetual, and the Constitution – though not amended to adjust to that – must nevertheless adjust.

That is a constitutional dilemma that confronts the nation’s leaders on a daily, even an hourly basis: how far can the government go to protect the nation’s security when doing so takes away or at least reduces individual liberty?

There are many areas of current public policy where that question can be asked appropriately, but one in which it is being asked with increasing intensity is in the nation’s struggle to decide the reach of the government’s global spying system, the highly sophisticated and largely secret endeavor of gathering electronic information about actual or potential threats of terrorism, in hopes of thwarting another 9/11 attack.

America has been engaged in a high-stakes debate about that system ever since the summer of 2013, when a former government computer analyst, Edward J. Snowden, told the press of the massive scope of the federal monitoring of telephone or communications traffic between the U.S. and overseas and, indeed, inside the U.S. itself.

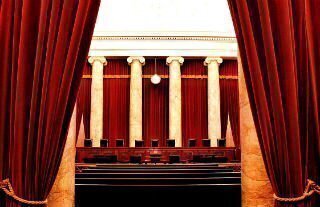

Since those revelations, the nation has learned much about how a secret court has actually operated, in facilitating that monitoring by issuing a series of back-to-back orders directed to the providers of telecommunications data. That tribunal is the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, made up of active federal judges who are assigned by the Chief Justice to sit on that court temporarily.

It is now clear that, as the government sought increasingly wide authority to conduct such surveillance, Congress agreed to go along, and the secret court with its expanded power seldom balked in response to government requests. As this scenario has become increasingly known to the public, the calls have grown for a new, independent look at the constitutionality of the entire enterprise.

There are only a few places in government where such a new analysis could be undertaken. Congress, of course, could take on the task, but the political reality is that the global terrorism threat is an impediment to a searching critique in either house of Congress or in its committees. The Executive Branch could take more responsibility for limiting its requests for new monitoring, and the President and others have insisted that they have done so, but that, too, is inhibited by political reality and the abiding resistance of the intelligence community itself.

The third branch, the Judiciary, would be a place for critics to turn, and, indeed, quite a number have tried. There have been a good many lawsuits challenging the sweeping scope of the data-gathering, but so far none of those has been allowed by the courts to go all the way to a final decision on the core constitutional issues. With the process still heavily (if not completely) shrouded in official secrecy, people or institutions believing that their communications have been monitored have not been able to prove that sufficiently to make their constitutional challenge.

The Constitution’s Article III requires that there be an actual “case or controversy” before a case may go forward in a federal court, and someone has to be able to show that they have been injured by government action in order to demonstrate that there is a live controversy. So far, no challenger has been able to make that case.

What deeply agitates the critics of the global spying program is that the Constitution has no provision that allows the Constitution to be put on hold during a time of peril in a dangerous world, and yet, they argue, something like a suspension has occurred – at the secret court, and perhaps elsewhere in government.

The most that critics may be able to do, at this stage, is to point out – in specific detail – the basis for their claims that the Constitution is not being followed faithfully, in hopes of keeping a national conversation going in a calm and reasoned way as they attempt to show that constitutional changes could actually be made, without sacrificing security.