Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s constitutional literacy adviser, looks at a federal court’s decision to extent First Amendment protections to a drug company marketing its products to physicians.

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

“‘This is huge,’ said Jacob Sherkow, an associate professor at New York Law School. ‘There have been other instances a court has held off-label marketing [of medicines] is protected by the First Amendment, but this is the first time, I think, that any federal court has held in such a clear, full-throated way that off-label marketing is protected by the First Amendment.’…Harvard Medical School professor Jerry Avron said he found ‘the decision very troubling. It’s a big push off on to a very slippery slope, a very steep slippery slope toward removing the government’s authority to limit the claims that drug companies can make about the effectiveness of their products.’”

– Excerpts from a story in The Washington Post on August 8, describing reactions by medical experts to a new decision by U.S. District Judge Paul A. Engelmayer of New York City, clearing the way for a New Jersey drug company to promote with doctors the use of one of its heart medicines – a use that has not won federal government approval.

WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

For more than the first century and a half that the First Amendment was in the Constitution, it was generally understood that its free-speech guarantees did not apply to commercial messages, such as advertising. The Supreme Court confirmed that view in a 1942 decision involving commercial handbills.

That understanding gave way, however, some 34 years later, when the court, in a case involving promotional ads about drug prices to consumers, ruled that commercial messages do, in fact, get some First Amendment protection. The Justices have been working out since then just how much protection there will be.

Any constitutional protection, though, has always depended upon the commercial messaging being truthful and not deceptive. The government has had ample power to police false and misleading communication – in the stock-investing field, in advertising generally, and in the promotion of medicines and drug supplements.

Beginning some three years ago, though, advocates of greater First Amendment protection have been attempting to loosen the government’s controls on a specific kind of commercial speech: the messages that drug manufacturers convey to doctors to try to persuade them to write prescriptions for their patents’ use of those companies’ products.

It has been true for decades that, if a prescription drug has not been approved by the federal Food and Drug Administration as safe and effective for humans, the sales representatives of a pharmaceutical company cannot legally promote it with doctors. That kind of promotion is considered “misbranding,” and the law carries both criminal and civil penalties for violations.

But even when the FDA has approved a particular drug for a specific treatment protocol – such as treating a particular medical condition – the company cannot legally promote it with doctors for any other use. That has been true even though it is not illegal for doctors to prescribe so-called “off-label” uses of a drug, and it is now common medical practice to do so because experience has shown that many drugs do have beneficial uses beyond those that the FDA has specifically approved.

In 2012, a federal appeals court put that restriction in serious doubt in a ruling in the case of United States v. Caronia. That court declared that it would raise significant First Amendment questions if FDA pursued a misbranding claim just because a drug company had promoted a non-approved use of a medicine, and did so in a truthful and non-deceptive way. So, the decision reinterpreted misbranding law to save it from the First Amendment.

Although that was a major setback for FDA, it chose not to take the case on to the Supreme Court, but instead opted to interpret that ruling very narrowly. The decision, it said, was limited to the specific facts in the case, and it the ruling left the agency with wide discretion to continue to bring misbranding claims for promotion of off-label, or non-approved, medical uses. The FDA continued to insist that it was a threat to health safety if doctors were being urged to prescribe a drug for an off-label use, even though that was not itself illegal.

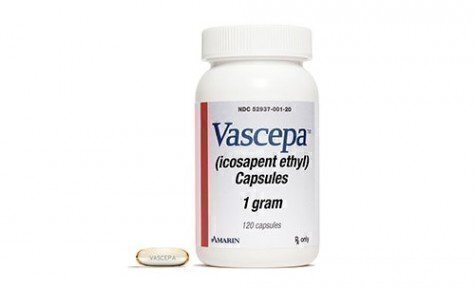

The FDA’s approach recently drew a sharp new challenge, however, when a New Jersey company and four New York doctors sued the FDA in federal court in New York City. The company, Amarin Pharma, Inc., had won FDA approval for a specific cardiac-related use of a product derived from fish oil, which it marketed under the trade name, Vascepa. But doctors had also been prescribing the drug for other heart conditions, different from the specific one that FDA had endorsed.

Because FDA had threatened a misbranding case against Amarin if it did not alter significantly the company’s off-label promotional messages, the company sought an order from U.S. District Judge Paul A. Engelmayer. The company contended that the FDA had seriously misinterpreted the appeals court decision in 2012 in the Caronia case.

Modern First Amendment law as it applied to commercial expression, the company contended, gave it a right to truthfully and without deception market Vascepa to doctors for the added treatment protocol. Judge Engelmayer agreed, and issued a temporary court allowing that kind of marketing to go forward.

Although the judge went to considerable lengths to try to keep his decision narrow, and even ordered Amarin to make some changes in its messaging to avert a misbranding claim, the resulting decision was a considerable defeat for FDA – one that left it with no realistic way to try to claim that it was narrow in scope. When an off-label message is conveyed to doctors for a medicine that previously had won FDA approval for another use, the judge declared flatly, it violates the First Amendment to threaten the drug company with misbranding when its new message was the truth and was not deceptive.

The case is not over yet in Judge Engelmayer’s court, because his ruling was only in a temporary form. Lawyers are to meet with him shortly to plan the case for the rest of the way. If Amarin ultimately wins a permanent order in favor of its off-label campaign, the FDA very likely would not be willing to leave it at that. The case could easily wind up in the Supreme Court.