Editor's Note: This commentary is part of a series presented in conjunction with the Center’s feature exhibition, Headed to the White House.

On June 1, 1812, President James Madison appealed to Congress to weigh a declaration of war against Great Britain. He said:

Whether the United States shall continue passive under these progressive usurpations and these accumulating wrongs, or, opposing force to force in defense of their national rights, shall commit a just cause into the hands of the Almighty Disposer of Events … is a solemn question which the Constitution wisely confides to the legislative department of the Government. In recommending it to their early deliberations I am happy in the assurance that the decision will be worthy of the enlightened and patriotic councils of a virtuous, a free, and a powerful nation.

With these words, Madison overturned eleven years of his and President Jefferson’s policy of defending American national security by means of economic coercion. The prior policy had sought to preserve domestic stability by fostering dispositions considered essential to democratic politics. That policy had to yield to the approach of “peace through strength” in the face of the intractable realities of traditional statecraft.

This episode of U.S. history conveys emblematically the necessities and choices falling to the hands of a president of the United States, and reflecting upon those necessities and choices discloses much about the nature and conception of the presidency. As the 2016 election approaches, we would be well counseled to weigh how far the U.S. presidency still manifests its original nature, conception and performance.

There are essentially three types of President that have obtained under the Constitution. We may describe them as the “presiding eminence,” the “super-legislator,” and the “tribune of the people.” While these types will seem self-explanatory, it will be useful to spell them out.

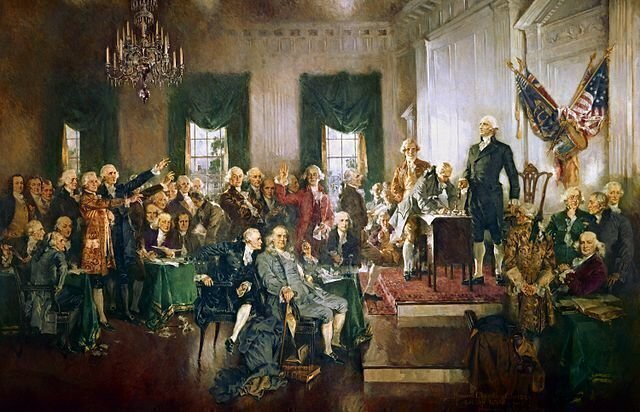

The presiding eminence fills the presidential chair primarily from the perspective of “overseeing” the democratic order. That reflects the limited sense in which the U.S. executive is somewhat monarchical in cast. The role answers to the constitutional necessity for the President to set the political agenda and to play a stabilizing role in fostering the dynamics of democratic decision-making. In this role, the President is not primarily a decision-maker, but makes decisions when circumstances warrant high-level intervention to avert destabilizing or security-endangering developments. The classic example of this is George Washington’s 1793 “Proclamation of Neutrality,” which aimed to avoid embroiling the U.S. in the European wars of that day (an objective of the Directory in France).

In the absence of the pressure for imminent decision, the presiding eminence leaves political decisions to eventuate from the process of democratic deliberation without placing a hand on the scales. As such, therefore, the presiding eminence is “above” party. Such a President will, however, identify matters of political significance that should be the subject of democratic deliberation (hence, the importance of the “State of the Union” address).

The super-legislator, in comparison, actively seeks to guide democratic deliberation toward preferred policy options. The President’s role in the legislative process via the qualified veto (which amounts to one-sixth of the legislative power) is viewed not merely as a negative safeguard against precipitate or unwise legislation, but also as an opportunity to structure and enforce policy judgments for the nation. That role was given its decisive theoretical articulation by Woodrow Wilson but received its fullest practical expression in the hands of Franklin Roosevelt. Lyndon Johnson also proved adept at it, despite lacking the ultimate capability to retain office and to capitalize on the opportunities thus afforded.

It is worth observing, moreover, that when Wilson advanced his conception of the presidency he did so as part and parcel of advancing an argument about the need to govern beyond the limits of the Constitution. That is, he thought the Constitution insufficiently concentrated decision-making in a programmatic manner, and that this deficiency required adopting further means to identify and advocate for a will of the society apart from the process of democratic deliberation. Or, to put it more precisely, Wilson believed that democratic deliberation needed to be forcefully directed by administrative vision. The super-legislator is the source of that vision, as the head of a majority party.

The third presidential role is that of “tribune of the people.” The tribune intersects with, but is not identical to, the super-legislator. Wilson also provided a theoretical articulation of this role, since the element of speaking for the “will of the people” captures the essence of the tribune. To be a tribune of the people, however, does not require fulfilling the role of super-legislator. The first example of the tribune is Andrew Jackson, who first gave evidence of elevating mass opinion as the basis of political judgment in democratic deliberation.

Mass opinion, the opinion of the majority, is distinguished from the “will of the society” in a two-fold manner. First, it is focused on a class distinction: mass opinion as the opinion of the “common man.” Thus, it is populist and anti-elitist, while the “will of the society” affects to address the interests of all classes. Secondly, mass opinion is the express opinion of the majority, so far as it can be discerned, and not an outcome of the dynamics of political deliberation. It represents a non-deliberative standard of decision-making, which privileges the unfiltered strongest opinion at any given time. The tribune of the people lays a claim to rule outright rather than to participate in a structure of ruling.

Admixtures of these roles may occur in any given presidency. Franklin Roosevelt, for example, was presiding eminence and super-legislator; he was not a tribune because he did not represent purely the dispossessed. Ronald Reagan was presiding eminence and tribune (“government is not the solution; government is the problem”).

What we found in James Madison in 1812 and thereafter was the balancing sometimes required among the roles. Madison, like Jefferson, was a presiding eminence. Yet each also sought to provide policy direction in the deliberative process. The attempts, however, were of limited success, insofar as the main initiatives eventuated in concessions to reality, whether in the arena of national security or in the arena of domestic economic policy. Madison and Jefferson were unable to reverse the course and consequence of Hamiltonian economic policies and so were not, in that respect, super-legislators.

While Madison and Jefferson sought to give voice to public opinion through the instrumentality of political organization—hence, the political party—neither sought to perpetuate the party as the voice of the “common man.” Thus, while their administrations sometimes had the look of the tribunitial, neither actually assumed the title of tribune or populist. Moreover, Madison found himself needing to reverse course on fundamental policy alternatives, such as the Bank of the United States, conceding a constitutional interpretation opposed to his own and upholding the obligation to “preserve, protect, and defend” the Constitution. That is what he also did in taking the nation into the War of 1812.

In looking at the prospects for 2016, we may well query whether the United States can anticipate elevating to the presidency any one or combination of these three types of President and whether the consequences for the nation would be promising or discouraging in one case or the other.

William B. Allen is Emeritus Professor of Political Philosophy in the Department of Political Science and Emeritus Dean, James Madison College at Michigan State University. He served previously on the National Council for the Humanities and the United States Commission on Civil Rights. His extensive publications include Rethinking Uncle Tom: The Political Philosophy of H. B. Stowe (2009).